CONTENTS

PUBLISHERS NOTE

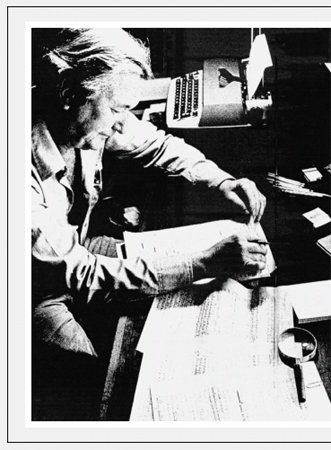

S EVERAL MONTHS BEFORE THE ONSET OF HIS FINAL illness, William Styron began to assemble materials for a collection of his personal essays. Most of the items in the present volume, including the title essay, are his selections. The final arrangement of the materials was made by Rose Styron, the authors widow. James L. W. West III, the authors biographer, prepared the texts for publication. Moviegoer and Too Late for Conversion or Prayer appeared initially in French translations in Le Figaro and Egoste. They are published here for the first time in English, in texts taken from Styrons manuscripts. A portion of A Literary Forefather appeared in the double fiction issue of the New Yorker for 26 June3 July 1995; the complete text survives among Styrons papers and is published here in full. Walking with Aquinnah, previously unpublished, was discovered among Styrons manuscripts after his death.

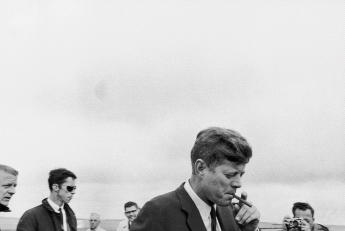

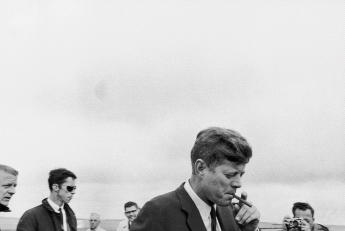

John F. Kennedy with cigar.

CECIL STOUGHTON, JOHN F. KENNEDY PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY, BOSTON.

HAVANAS in CAMELOT

L IKE MILLIONS OF OTHERS, I WATCHED TRANSFIXED in late April 1996 as the acquisitive delirium that swept through Sothebys turned the humblest knickknack of Camelot into a fetish for which people would pony up a fortune. A bundle of old magazines, including Modern Screen and Ladies Home Journal, went for $12,650. A photograph of an Aaron Shikler portrait of Jackienot the portrait itself, mind you, a photowas sold for $41,400. (Sothebys had valued the picture at $50 to $75.) A Swiss Golf-Sport stroke counter, worth $50 to $100 by Sothebys estimate, fetched an insane $28,750. But surely among the most grandiose trophies, in terms of its bloated price, was John Kennedys walnut cigar humidor, which Milton Berle had given the president in 1961 after having attached a plaque reading To J.F.K. Good HealthGood Smoking, Milton Berle 1/20/61. The comedian had paid $600 to $800 for it in that year. Thirty-five years later, poor Berle tried to buy the humidor back at Sothebys but dropped out of the bidding at $185,000.

The winner was Marvin Shanken, publisher of the magazine Cigar Aficionado, who spent $574,500 on an object the auctioneers had appraised at $2,000 to $2,500. Even at such a flabbergasting price the humidor should prove to play an important mascot role in the fortunes of Shankens magazine, which is already wildly successful, featuring (aside from cigars and cigar-puffing celebrities) articles on polo and golf, swank hotels, antique cars, and many other requirements for a truly tony lifestyle in the 1990s. After all, John F. Kennedy was no stranger to the nobby life, and what could be more appropriate as a relic for a cigar magazine than the vault in which reposed the Havanas of our last genuine cigar-smoking president?

I never laid eyes on the fabled humidor, but on the occasions I encountered Kennedy I sensed he must have owned one, protecting his precious supply, for he approached cigars with the relish and delight ofwell, an aficionado. Indeed, if I allow my memory to be given a Proustian prod, and recollect Kennedy at the loose and relaxed moments when our lives briefly intersected, I can almost smell the smoke of the Havanas for which hed developed such an impetuous, Kennedyesque weakness.

After the clunky Eisenhower years it was wonderful to have this dashing young guy in the spotlight, and soon there was nothing unusual in seeing the president posed, without apology or self-consciousness, holding a cigar. I had become friendly with two members of the Kennedy staff, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., and Richard Goodwin, both of whom were so passionate about cigars that smoking appeared to me to be almost a White House subculture. They would lecture me about cigars whenever I saw them in Washington. Havanas were, of course, the sine qua non, and, as an ignorant cigarette smoker still clinging miserably to an unwanted addiction, I found myself fascinated but a little puzzled by all the cigar talk, by the effusive praise for a Montecristo of a certain length and vintage, by the descriptions of wrappers and their shades, by the subtle distinctions made between the flavors of a Ramon Allones and a Punch. Stubbornly, I kept up my odious allegiance to cigarettes, but in my secret heart I envied these men for their devotion to another incarnation of tobacco, one that had been transubstantiated from mere weed into an object plainly capable of evoking rapture.

IN LATE APRIL OF 1962 I was one of a small group of writers invited to what turned out to be possibly the most memorable social event of the Kennedy presidency. This was a state dinner in honor of Nobel Prize winners. Schlesinger and Goodwin were responsible for my being includedat the time, Kennedy didnt know me, as they say, from Adamand it was a giddy pleasure for my wife, Rose, and me to head off to the White House on a balmy spring evening in the company of my friend James Baldwin, who was on the verge of becoming the most celebrated black writer in America. I recall that it was the only time I ever shaved twice on the same day.

Before dinner the booze flowed abundantly and the atmosphere crackled with excitement as J.F.K. and his beautiful lady joined the assembly and presided over the receiving line. Jack and Jackie actually shimmered. You would have had to be abnormal, perhaps psychotic, to be immune to their dumbfounding appeal. Even Republicans were gaga. They were truly the golden couple, and I am not trying to play down my own sense of wonder when I note that a number of the guests, male and female, appeared so affected by the glamour that their eyes took on a goofy, catatonic glaze.

Although I remained in control of myself, I got prematurely plastered; this did not damage my critical faculties when it came to judging the dinner. Id spent a considerable amount of time in Paris and had become something of a food and wine snob. Later, in my notebook, I ungratefully recorded that while the Puligny-Montrachet 1959, served with the first course, was more than adequate, I found the Mouton-Rothschild 1955, accompanying the filet de boeuf Wellington, lacking in maturity. The dessert, something called a bombe Caribienne, I deemed much too sweet, a real bomb.

Reviewing these notes so many years later, I cringe at my churlishness (including the condescending remark that the meal was doubtless better than anything Ike and Mamie served up), especially in view of the thrilling verve and happy spirits of the entire evening. Because of the placement of the tables I was seated at right angles to the president, and I was only several feet away when he rose from his own table and uttered his famous bon mot about the occasion representing the greatest gathering of minds at the White House since Thomas Jefferson dined here alone. The Nobelists roared their appreciation at this elegant bouquet, and I sensed the words passing into immortality.

Next page