Wilbur S. Shepperson Series in Nevada History

Series Editor: Michael S. Green

University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada 89557 USA

Copyright 2013 by University of Nevada Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Design by Kathleen Szawiola

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McArthur, Aaron.

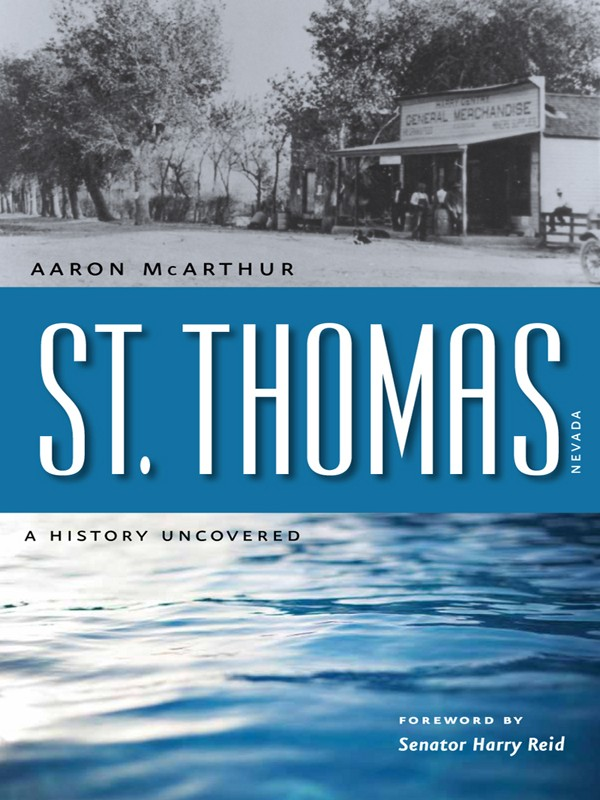

St. Thomas, Nevada: a history uncovered / Aaron McArthur.

pages cm. (Wilbur S. Shepperson series in Nevada history)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-87417-919-4 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-87417-920-0 (e-book) 1. Saint Thomas (Nev.)History. I. Title. II. Title: Saint Thomas, Nevada.

F849.S35M43 2013

979.3'13dc23 2013010402

Foreword

SENATOR HARRY REID

To some, the story of St. Thomas is a cautionary tale about water in the Southwestor, rather, the lack of water. The followers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) who settled at the confluence of the Virgin and Muddy Rivers in 1865 knew a thing or two about the importance of water. After traveling for weeks in wagons across an unforgiving desert, that trickle of water, flowing constant in summer and winter, must have looked like a mirage.

And so they built a life there. It was a hard life, by all accounts. There was no air-conditioning and little shade from the scorching summers of southern Nevada. Walking from cistern to cistern in the ruins of St. Thomas, it is evident water made life there possible. But watertoo much wateralso put an end to St. Thomas.

The town never had more than a few hundred residents, even before construction began on the Hoover Dam, originally named the Boulder Dam, in 1931. A massive team of Depression-era engineers and builders set out to construct a forty-eight-million-dollar hydroelectric dam and massive reservoir to tame the mighty Colorado River and distribute its life-giving waters throughout the Southwest. The reservoirLake Meadwould extend more than one hundred miles back from the great dam and wipe St. Thomas off the map.

The Gentry Hotel, with its curved facade and second-story balcony, would soon be underwater. So would the schoolhouse, the rows of cottonwoods the settlers planted for shade, and the car repair shop where bachelors would crowd around the town's first radio to listen to the news. A few residents refused to leave until the waters were lapping at their doorsteps. In the end, however, they all moved on.

The town would rise again, though. When a mighty drought began early in the twenty-first century, the bones of St. Thomas peeked out from below the water. Concrete foundations, tree stumps, and the steps of the old schoolhouse emerged. In fact, a ghost town that had once been seventy feet below the middle of a lake was now a mile or more from the water's edge.

Some called the reemergence in 2002 a reminder of the harsh character of the desert, of the delicate balance of nature that makes life possible in inhospitable lands. After all, the residents of St. Thomas were not the first to abandon the valley. Nearly a thousand years ago, the Anasazi tribe left after living there for more than a thousand years. Their population had grown too quickly, and the land could no longer support them. The history of St. Thomas holds lessons about sustainability, stewardship of the land, and the value of water in the desert. St. Thomas has more to teach us as well.

The town also emerged from beneath the water once in the 1950s and again in the mid-1960s. In those days, there were reunions among the bones of buildings. Men and women who were only children when the lake took their homes gathered again to recall the faith that brought their parents and grandparents to the desert in the first place. They recalled the community they had built despite the harsh weather and the history they shared despite the town's short life span. The lessons they took from the loss of St. Thomasand from its reemergencewere not about water. They were about community.

When St. Thomas emerged in 2002, however, there was no one left to remember that community. Almost everyone who ever lived in St. Thomas is dead. There will not be any more reunions. And that is a different kind of cautionary tale.

When I wrote my history of Searchlight, Nevadathe tiny hard-rock mining town where I grew upI did twenty interviews or more with elderly residents, gathering stories from the early days of the last century. By the time I finished the book, seven of them were dead. It is a simple reality that eventually, no matter how long you live, you will lose your history if you do not write it down.

St. Thomas was an LDS community, and LDS are unusually good at writing down history. The records of St. Thomas are therefore relatively detailed. Searchlight, on the other hand, had thirteen brothels but not a single church. We did not have the kind of record keeping there that will keep St. Thomas alive for generations to come, even though it has been gone for generations already.

Still, St. Thomas is a reminder that history is fleeting. The primary sourcesour parents and their parentswill not be around forever. So we must be good stewards of their stories, preserving and conserving them as we do the natural resources that make life possible in the desert.

Preface

This book began as an administrative history of the St. Thomas, Nevada, site for the National Park Service. When the ruins of the town began to emerge from the murky depths of Lake Mead in 1999, the National Park Service realized that it needed to know how to administer the site. A few years later, I was recruited to write this administrative history by the late Hal Rothman, professor of history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. During the writing, I realized that the site had much to teach about western water issues and western history in general. It is this larger story of St. Thomas that I have expanded into this book.

There are many people who have helped in innumerable ways to bring this book to fruition. The staff at the LDS Archives, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Denver, L. Tom Perry Special Collections at Brigham Young University, and Lied Library Special Collections at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, went out of their ways to assist in my research. Though I spent less time at these institutions, I also found great help at the Denver Public Library, the Nevada State Museum, the Clark County Museum, Dixie State College, and the Boulder City Museum. Thanks are due to Virginia Beezy Tobiasson, who helped with some very good research leads.

I will be eternally grateful to Hal Rothman. He introduced me to David Louter, Steve Daron, and Rosie Pepito of the National Park Service, who were all wonderful resources during the research and writing phases and whose insights made this book better. Thanks are also due to Peter Michel for granting me time to work on the manuscript.

Thanks to my wife, Xela, and kids, Benjamin and Zion. Thank you for being patient with me during the time I spent writing and revising the manuscript. Sam, I haven't forgotten, SDG.