Robert Graves - The Twelve Caesars

Here you can read online Robert Graves - The Twelve Caesars full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: RosettaBooks, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

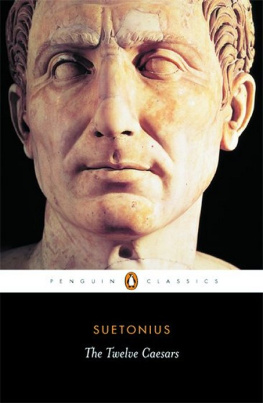

- Book:The Twelve Caesars

- Author:

- Publisher:RosettaBooks

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Twelve Caesars: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Twelve Caesars" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Twelve Caesars — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Twelve Caesars" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Twelve Caesars

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus

translated by Robert Graves

Copyright

The Twelve Caesars

Copyright 1957 by Robert Graves, renewed 1985 by Robert Graves

Cover art, special contents, and Electronic Edition 2014 by RosettaBooks LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover jacket design by Carly Schnur

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795337642

Not much is known about the life of Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. He was probably born in 69 A.D. the famous year of four Emperorswhen his father, a Roman knight, served as a colonel in a regular legion and took part in the Battle of Baetricum. From the letters of Suetoniuss close friend Pliny the Younger we learn that he practised briefly at the bar, avoided political life, and became chief secretary to the Emperor Hadrian (11738 A.D. ). The historian Spartianus records that he was one of several Palace officials, including the Guards Commander, whom Hadrian when he returned from Britain dismissed for behaving indiscreetly with the Empress Sabina. Suetonius seems to have lived to a good age. The titles of his books are recorded as follows: The Twelve Caesars; Royal Biographies; Lives of Famous Whores; Roman Manners and Customs; The Roman Year; Roman Festivals; Roman Dress; Greek Games; Offices of State; Ciceros Republic; The Physical Defects of Mankind; Methods of Reckoning Time; An Essay on Nature; Greek Objurgations; Grammatical Problems; Critical Signs Used in Books. But apart from fragments of his Illustrious Writers, which include short biographies of Virgil, Horace, and Lucan, the only extant book is The Twelve Caesars, the most fascinating and richest of all Latin histories.

Suetonius was fortunate in having ready access to the Imperial and Senatorial archives and to a great body of contemporary memoirs and public documents, and in having himself lived nearly thirty years under the Caesars. Much of his information about Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero comes from eye-witnesses of the events described. Apparently he took care to check facts wherever possible, and often quotes conflicting evidence without bias, which was not the habit of Tacitus or other later historians. If his credulousness about omens and prodigies is discounted, he seems trustworthy enough, his only prejudice being in favour of firm, mild rule, with a regard for the human decencies. As the famous Dean Liddell wrote:

His language is very brief and precise, sometimes obscure, without any affection or ornament. He certainly tells a prodigious number of scandalous anecdotes about the Caesars, but there was plenty to tell about them; and if he did not choose to suppress those anecdotes which he believed to be true, that is no imputation on his veracity. As a great collection of facts of all kinds, his work on the Caesars is invaluable

And Pliny, who persuaded the Emperor Trajan to grant Suetonius the immunities usually granted only to a father of three children, though he had none, wrote that the more he knew of Suetonius, the greater his affection for him grew; I have had the same experience.

This version of The Twelve Caesars is not intended as a school crib; the genius of Latin and the genius of English being so dissimilar that a literal rendering would be almost unreadable. For English readers Suetoniuss sentences, and sometimes even groups of sentences, must often be turned inside-out. Wherever his references are incomprehensible to anyone not closely familiar with the Roman scene, I have also brought up into the text a few words of explanation that would normally have appeared in a footnote. Dates have been everywhere changed from the pagan to the Christian era; modern names of cities used whenever they are more familiar to the common reader than the classical ones; and sums in sesterces reduced to gold pieces, at 100 to a gold piece (of twenty denarii), which resembled a British sovereign. The problem of finding suitable English equivalents for Latin technical words is exemplified in Imperator. This, at first, meant simply army commander; next it became a title of honour which a general might earn by an important victory; then it was placed as a title of honour after, or (more flatteringly) before, the name of one of the ruling Caesars, whether or not he had won any victories; finally, it was used in an absolute sense to mean Emperor.

I might have prefaced the translation with an essay on the Roman Republican Constitution and the merciless struggle between the popular and aristocratic parties in which Julius Caesar became involved, and which ended only with the triumph of Augustus; but most readers will perhaps prefer to plunge straight into the story and pick up the threads as they go along.

My gratitude to Alastair Reid and Kenneth Gay for helping me with this enjoyable task.

R. G.

Dey, Majorca, Spain

1957

AFTERWARDS DEIFIED

(The introductory paragraphs on the origins of Caesars family are lost in all manuscripts.)

Gaius Julius Caesar lost his father at the age of fifteen. in this fellow Caesar.

2. Caesar first saw military service in Asia, where he went as aide-de-camp to Marcus Thermus, the provincial governor-general. When Thermus sent Caesar to raise a fleet in Bithynia, he wasted so much time at King Nicomedess court that a homosexual relationship between them was suspected, and suspicion gave place to scandal when, soon after his return to headquarters, he revisited Bithynia: ostensibly collecting a debt incurred there by one of his freedmen. However, Caesars reputation improved later in the campaign, when Thermus awarded him the civic crown of oak-leaves, at the storming of Mytilene, for saving a fellow-soldiers life.

3. He also campaigned in Cilicia under Servilius Isauricus, but not for long, because the news of Sullas death sent him hurrying back to Rome, where a revolt headed by Marcus Lepidus seemed to offer prospects of rapid advancement. Nevertheless, though Lepidus made him very advantageous offers, Caesar turned them down: he had small confidence in Lepiduss capacities, and found the political atmosphere less promising than he had been led to believe.

4. After this revolt was suppressed, Caesar brought a charge of extortion against Cornelius Dolabella, an ex-consul who had once been awarded a triumph, but failed to secure a sentence; so he decided to visit Rhodes until the resultant ill-feeling had time to die down, meanwhile taking a course in rhetoric from Apollonius Molo, the best living exponent of the art. Winter had already set in when he sailed for Rhodes and was captured by pirates off the island of Pharmacussa. They kept him prisoner for nearly forty days, to his intense annoyance; he had with him only a physician and two valets, having sent the rest of his staff away to borrow the ransom money. As soon as the stipulated fifty talents arrived (which make 12,000 gold pieces), and the pirates duly set him ashore, he raised a fleet and went after them. He had often smilingly sworn, while still in their power, that he would soon capture and crucify them; and this is exactly what he did. Then he continued to Rhodes, but Mithridates was now ravaging the near-by coast of Asia Minor; so, to avoid the charge of showing inertia while the allies of Rome were in danger, he raised a force of irregulars and drove Mithridatess deputy from the provincewhich confirmed the timorous and half-hearted cities of Asia in their allegiance.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Twelve Caesars»

Look at similar books to The Twelve Caesars. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Twelve Caesars and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.