Contents

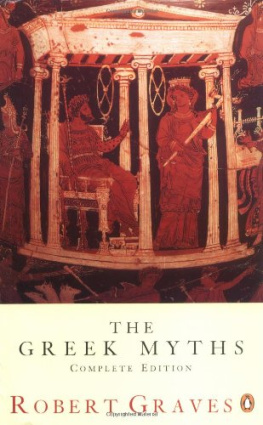

Robert Graves

THE GREEK MYTHS

The Complete and Definitive Edition

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in two volumes by Pelican Books 1955

Both volumes reprinted with amendments 1957

Revised editions of both volumes 1960

Combined edition published in Penguin Books 1992

Reissued in this edition 2017

Copyright Robert Graves, 1955, 1960

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-241-98338-6

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinUKbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE GREEK MYTHS

Robert Graves was born in 1895 in Wimbledon, son of Alfred Percival Graves, the Irish writer, and Amalia Von Ranke. He went from school to the First World War, where he became a captain in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. His principal calling was poetry, and his Selected Poems have been published in the Penguin Poets series. Apart from a year as Professor of English Literature at Cairo University in 1926 he earned his living by writing, mostly historical novels which include: 1, Claudius; Claudius the God; Sergeant Lamb of the Ninth; Count Belisarius; Wife to Mr Milton (all published as Penguins); Proceed, Sergeant Lamb; The Golden Fleece; They Hanged My Saintly Billy; and The Isles of Unwisdom. He wrote his autobiography, Goodbye to All That, in 1929 and it rapidly established itself as a modern classic. The Times Literary Supplement acclaimed it as one of the most candid self-portraits of a poet, warts and all, ever painted, as well as being of exceptional value as a war document. His two most discussed non-fiction books are The White Goddess, which presents a new view of the poetic impulse, and The Nazarine Gospel Restored (with Joshua Podro), a re-examination of primitive Christianity. He translated Apuleius, Lucan and Suetonius for the Penguin Classics, and compiled the first modern dictionary of Greek mythology, The Greek Myths. His translation of The Rubiyt of Omar Khayym (with Omar Ali-Shah) is also published in Penguins. He was elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford in 1961, and made an Honorary Fellow of St Johns College, Oxford, in 1971.

Robert Graves died on 7 December 1985 in Majorca, his home since 1929. On his death The Times wrote of him, He will be remembered for his achievements as a prose stylist, historical novelist and memorist, but above all as the great paradigm of the dedicated poet, the greatest love poet in English since Donne.

The death of the Old Bull of the Year apparently poleaxed, and the birth of the New Years Bull-Calf from a date cluster; under the supervision of a Cretan priestess, who identifies herself with the palm-tree. From a Middle-Minoan bead-seal in the authors collection (diameter enlarged 1 times). About 1900 B.C.

Foreword

Since revising The Greek Myths in 1958, I have had second thoughts about the drunken god Dionysus, about the Centaurs with their contradictory reputation for wisdom and misdemeanour, and about the nature of divine ambrosia and nectar. These subjects are closely related, because the Centaurs worshipped Dionysus, whose wild autumnal feast was called the Ambrosia. I no longer believe that when his Maenads ran raging around the countryside, tearing animals or children in pieces (see ).

On an Etruscan mirror the amanita muscaria is engraved at Ixions feet; he was a Thessalian hero who feasted on ambrosia among the gods (see ) was that he broke the taboo by inviting commoners to share his ambrosia.

Sacred queenships and kingships lapsed in Greece; ambrosia then became, it seems, the secret element of the Eleusinian, Orphic and other Mysteries associated with Dionysus. At all events, the participants swore to keep silence about what they ate or drank, saw unforgettable visions, and were promised immortality. The ambrosia awarded to winners of the Olympic footrace when victory no longer conferred the sacred kingship on them was clearly a substitute: a mixture of foods the initial letters of which, as I show in What Food the Centaurs Ate, spelled out the Greek word mushroom. Recipes quoted by Classical authors for nectar, and for cecyon, the mint-flavoured drink taken by Demeter at Eleusis, likewise spell out mushroom.

I have myself eaten the hallucigenic mushroom, psilocybe, a divine ambrosia in immemorial use among the Masatec Indians of Oaxaca Province, Mexico; heard the priestess invoke Tlaloc, the Mushroom-god, and seen transcendental visions. Thus I wholeheartedly agree with R. Gordon Wasson, the American discoverer of this ancient rite, that European ideas of heaven and hell may well have derived from similar mysteries. Tlaloc was engendered by lightning; so was Dionysus (see ). Tlaocs emblem was a toad; so was that of Argos; and from the mouth of Tlalocs toad in the Tepentitla fresco issues a stream of water. Yet at what epoch were the European and Central American cultures in contact?

These theories call for further research, and I have therefore not incorporated my findings in the text of the present edition. Any expert help in solving the problem would be greatly appreciated.

R. G.

Dey, Majorca,

Spain, 1960.

Introduction

The medieval emissaries of the Catholic Church brought to Great Britain, in addition to the whole corpus of sacred history, a Continental university system based on the Greek and Latin Classics. Such native legends as those of King Arthur, Guy of Warwick, Robin Hood, the Blue Hag of Leicester, and King Lear were considered suitable enough for the masses, yet by early Tudor times the clergy and the educated classes were referring far more frequently to the myths in Ovid, Virgil, and the grammar school summaries of the Trojan War. Though official English literature of the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries cannot, therefore, be properly understood except in the light of Greek mythology, the Classics have lately lost so much ground in schools and universities that an educated person is now no longer expected to know (for instance) who Deucalion, Pelops, Daedalus, Oenone, Laocon, or Antigone may have been. Current knowledge of these myths is mostly derived from such fairy-story versions as Kingsleys