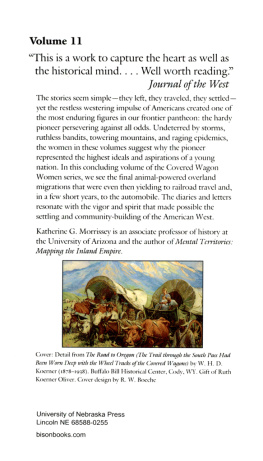

1984 by Kenneth L. Holmes. Reprinted by arrangement with the Arthur H. Clark Company.

Introducton to the Bison Books Edition 1996 by the University of Nebraska Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Library of Congress has cataloged Vol. 1 as:

Covered wagon women: diaries & letters from the western trails, 1840-1849 / edited and compiled by Kenneth L. Holmes; introduction to the Bison Books edition by Anne M. Butler,

p. cm.

Originally published: Glendale, Calif.: A. H. Clark Co., 1983.

Volume I.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 0-8032-7277-4 (pa: alk. paper)

1. Women pioneersWest (U.S.)Biography. 2. West (U.S.)History. 3. West (U.S.)Biography. 4. Overland journeys to the Pacific. 5. Frontier and pioneer lifeWest (U.S.) I. Holmes, Kenneth L.

F591.C79 1996

978dc20 95-21200 CIP

Volume 2 introduction by Lillian Schlissel.

ISBN 0-8032-7274-X (pa: alk. paper)

Volume 3 introduction by Susan Armitage.

ISBN-10: 0-8032-7287-1 (pa: alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-7287-3 (electronic: e-pub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-7287-3 (electronic: mobi)

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Introduction to the Bison Books Edition

Susan Armitage

One of the earliest and most evocative portraits of the overland pioneers was penned by Francis Parkman in The Overland Trail (serialized in 1847, published in book form in 1849). Observing a group of overlanders as they reached Fort Laramie, Parkman wrote:

A crowd of broad-brimmed hats, thin visages, and staring eyes, appeared suddenly at the gate. Tall awkward men, in brown homespun; women with cadaverous faces and long lank figures, came thronging in together, and, as if inspired by the very demon of curiosity, ransacked every nook and comer of the fort.

This remarkable vignette, which captures the moment when the pioneers made their last contact with organized American society before moving farther west into the unknown, provokes our curiosity to know more about them. Parkman, whose real interest lay with Indians and mountain men, tells us little more. To get closer, we must turn to the diaries the overlanders wrote about their westward journeys.

Until about twenty years ago, the Overland Trail story was generally understood as a male adventure epic. The vast majority of known diaries were by men rushing to California after gold was discovered in 1848. Because of the preponderance of these Gold Rush accounts, the smaller Oregon migration was neglected, and so was the family nature of it. In contrast to the temporary intent of California-bound travelers, families went to Oregon to settle, to farm, and to stay. Family migration, as opposed to the individual urge to get to California quickly, was a minor theme in most accounts of the Overland Trail.

As womens history developed as an academic specialty in the 1970s, womens trail diaries were rediscovered, and two historians, John Mack Faragher in Women and Men on the Overland Trail (1979) and Lillian Schlissel in Womens Diaries of the Westward Journey (1982), made important contributions to their interpretation. Their most important finding was simply that the trail experience, like every other kind of life experience, was gendered. Womens feelings about the westward journey differed from mens in small but vital ways. For men, the trail experience was a break from customary farm routines. Planning and safely executing the trip posed a significant challenge and there was adventure in meeting the challenge. For women occupied with the customary female activities of feeding their families and caring for young children, a significant part of the trail experience was the struggle to maintain customary family household patterns under difficult circumstances. In the female experience of the westward journey, endurance rather than adventure predominated.

At first, this gendered analysis of the trail diaries was resisted by many western historians, who tended to defend older, well-documented interpretations. Today, however, postmodern scholarship and womens history alike direct our attention not to unifying myths but to the complexity and variety of individual accounts, in which gender is one important (but not exclusive) variable. Furthermore, the decidedly antiheroic tenor of contemporary thought has affected the interpretation of the Overland Trail as much as it has other national icons. John Unruhs monumental The Plains Across (1979) emphasized not the adventure but the overwhelming tedium of the four- to six-month westward trip to California, Oregon, or Salt Lake City, an emphasis fully corroborated in womens diaries. The Covered Wagon Women series contributes to this antimythic spirit by publishing hitherto unknown womens accounts in all their variety. The diaries in this particular volume, of women travelers in 1851, add new information to the historical record. As Kenneth Holmess story of their acquisition makes clear, new diaries are still being discovered today, almost 150 years after their recording. Taken together and separately, the seven diaries in this volume tell us some things about general trail conditions in 1851, about the particular circumstances of individual trains, and about the experience of the women diarists themselves.

The approximately seven thousand people who ventured west in 1851 found it was a good year to travel the Oregon Trail. The dramatic decrease in numbers from 1850 eased the competition for good camping spots (those with adequate grass, water, and fuel) and decreased the chance of a recurrence of the deadly scourge of 1850, cholera, which was caused by contaminated drinking water. Because of the vast numbers of gold rushers in 1849 and 1850, the trail was now clearly marked in wagon ruts that remain in some places today. Guidebooks were more reliable, and an ever-increasing number of trading posts and ferriesin addition to the major Mormon settlement in Salt Lake Cityhad sprung up along the route.

For all of its improvements, the overland journey tested each of the seven very different diarists, as it doubtless did the other approximately three thousand westering women of 1851 who did not leave accounts of their journey. What can we learn about the 1851 journey from these seven women? Who were they, and what do their diaries tell us about the female trail experience?

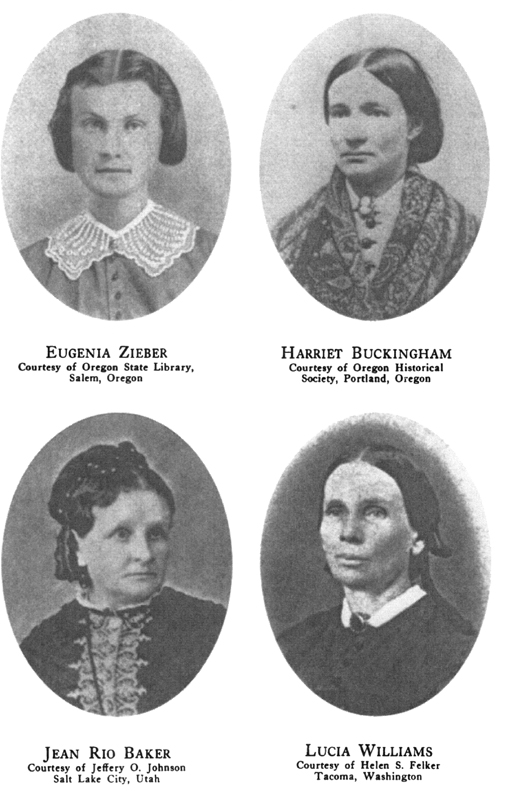

First, the matter of identification. Womens historians have found that identifying women by age and social class (the criteria by which we generally distinguish men) is inadequate for women. Family status is a crucial additional variable, and this is abundantly clear in this volumes diaries. Three accounts are by young, unmarried women: Harriet Buckingham (age nineteen), Elizabeth Wood (twenty-three) and Eugenia Zeiber (eighteen). Buckingham and Zeiber traveled with family parties and had at least partial responsibility for younger kin and probably assisted with cooking. Elizabeth Wood apparently traveled with others who were not kin and seemed to have no childcare responsibilities. All three of these young women offer cheerful accounts of their largely enjoyable trips. Two other young women, Amelia Hadley and Susan Cranston, married but childless, write rather more somber diaries. Cranstons diary in particular, with its obsessive grave-counting, can only be described as depressed. The two oldest women, Lucia Williams (age thirty-five) and Jean Rio Baker (forty-one) each suffered the death of a child during the journey and their accounts reflect this loss. Thus even within this small sample, the range of experience and attitude is enormous.