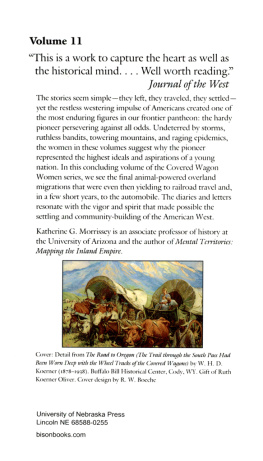

Contents

1983 by Kenneth L. Holmes. Reprinted by arrangement with the Arthur

H. Clark Company.

Introduction to the Bison Books Edition 1995 by the University of

Nebraska Press

All rights reserved

The paper in this book meets the minimum requirements of American

National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for

Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-l984.

First Bison Books printing: 1995

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

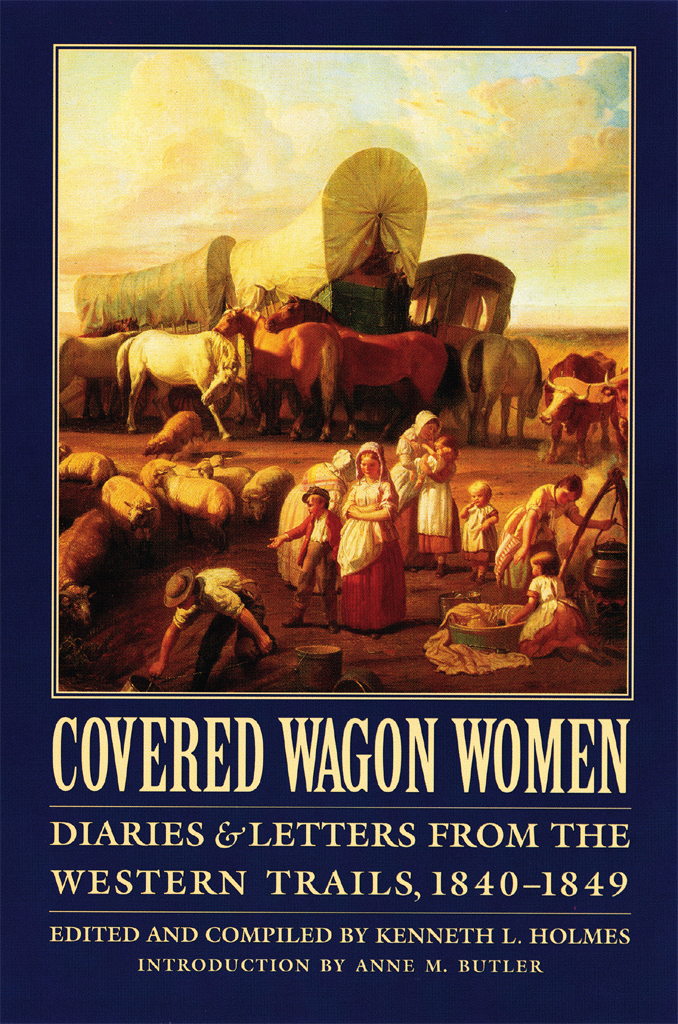

Covered wagon women: diaries & letters from the western trails, 18401849 / edited and compiled by Kenneth L. Holmes; introduction to the Bison

Books edition by Anne M. Butler.

p. cm.

Originally published: Glendale, Calif.: A. H. Clark Co., 1983.

Reprinted from volume one of the original eleven-volume edition T.p. verso.

Volume I.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-8032-7277-4 (pa: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4962-2554-2 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-4962-2555-9 (mobi)

1. Women pioneers-West (U.S.)-Biography. 2. West (U.S.)-History. 3. West (U.S.)-Biography. 4. Overland journeys to the Pacific.

5. Frontier and pioneer life-West (U.S.) 1. Holmes, Kenneth L.

F591.C79 1996

978dc20

95-21200 CIP

Reprinted from volume one (1983) of the original eleven-volume edition titled Covered Wagon Women: Diaries and Letters from the Western Trails, 18401890, published by the Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, California.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Dedicated to

C LIFFORD M ERRILL D RURY

First White Women Over the Rockies,

laid the foundation for much

of what follows here.

INTRODUCTION TO THE BISON BOOKS EDITION

Anne M. Butler

O that I had time and talent

to describe this curious country.

Elizabeth Dixon Smith

Happily, the concept of a womens West no longer surprises us. Women were shaped by the West, but they did their own share of shaping, leaving a female signature on land and lives. It took Americans several decades to acknowledge this historical reality. The recognition came slowly, but we have moved beyond an earlier perception of the West as an arena reserved for male exploits. While once historians described the West as the exclusive territory of trappers, cowboys, miners, and soldiers, all of whom sprang from Anglo stock, the region is now recognized as far more gendered in its history. Women like Elizabeth Dixon Smith, the articulate and observant pilgrim quoted above, have identity and voice in the annals of western history.

Scholarly and popular publications alike have pushed back the confining parameters of western history to reveal a rich panorama of social, economic, and political forces that molded womens lives. Noted historians have turned out revealing and important works about women in the West. Yet, even as the scholarly investigation of western women has expanded, so the discussion over the nature of the experience has intensified. The more we know, the harder it seems to be to pinpoint the meaning of life for pioneer women in the American West. Did migrant women look to the West with quivering fear or joyful anticipation? What changes threaded through family interactions as a result of the struggle to relocate in the West? Were men and women affected differently by these incredible journeys? Did the pioneer experience exacerbate conditions of oppression for American women, or did it release women from cultural and economic limitations? Did the arrival of white women add to the mounting racial conflicts in the West, or did women reach across cultural divisions and perceive gender commonalities? Did pioneer wives and mothers encourage general female independence, or did they intensify the oppression of all women through their own cultural and habitual sexism and racism? Clearly, the response of Anglo women to the pioneer era remains a thorny issue for historians.

Much of the scholarly literature rests on the premise that the time period, which included a growth in American manufactures, a flood of new immigrants, and an explosion in domestic migration and western land grabbing, also saw the rise of a powerful social philosophy, ultimately known as the cult of true womanhood. spirit that encouraged individualism and personal achievement, a counter message cast a long shadow across the lives of women. While men partook of coarse national impulses. women were valued in the private sphere, inside the American home. The message women got effectively shut them out of opportunities for rigorous education, professional advancement, political involvement, and economic independence. This exclusion occurred simultaneously with the championing of education, advancement, involvement, and independence all along the ladder of Americas masculine hierarchy.

Thus, the privacy of the home came to circumscribe the legitimate arena for womanly attention. Within the domain of the home, women could cultivate traits designed to make them pure, passive, and pious. In a rough-and-tumble era of American history, women, denied access to public avenues of power, became exclusively responsible for creating a family sanctuary. With this charge to be the moral guardians of the family, society dictated that a womans fulfillment centered' on domesticity, childbearing, and the reflected glory of her husband.

Although the notion seems incredibly simplistic, almost amusing, it assumed a power unto itself. It infiltrated all aspects of womanhood-physical, intellectual, and spiritual-producing inflexible rules of female conduct. With a hefty assist from ministers, physicians, journalists, and a wide range of selfappointed authorities, the cult of true womanhood emerged as the single definition of the female experience.

At odds with this rigorous standard were the public values of the day, the institution of slavery and the specific lives of thousands of women-poor immigrants, factory workers, women of color-for whom the code had neither practical nor appealing application. Such women ignored the cults dicta, intent on actively salvaging as much of their own culture as possible within the context of an ever stronger white Protestant America. However, the cult of domesticity and passivity touched the hearts and minds of many women, especially of the hard-working white lower-middle class, who yearned for a life that would allow them the designation of lady.

This powerful ideology of acceptable womanhood provides the lens through which scholars have examined a range of womanly activities across the spectrum of U.S. history. Grounded in eastern intellectual and social forces, the cult of true womanhood invites western applications, since, with its rigid female limitations, it contrasts so dramatically with burgeoning frontier society. Perhaps nowhere in the nation, between 1830 and 1900, were power strategies. self-aggrandizement, and personal advancement played out with cruder force than in the American West. The more recent bonding of a feminine eastern ideology with the masculine frontier West has shifted the historians lens over time, illuminating new shadings and angles within western womens experiences and providing a rich literature for consideration.