Contents

1983 by Kenneth L. Holmes. Reprinted by arrangement with the Arthur H. Clark Company.

Introduction to the Bison Books Edition 1996 by the University of Nebraska Press

All rights reserved

The paper in this book meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

First Bison Books printing: 1996

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Library of Congress has cataloged Vol. I as:

Covered wagon women: diaries & letters from the western trails, 1840-1849 I edited and compiled by Kenneth L. Holmes; introduction to the Bison Books edition by Anne M. Butler.

p. cm.

Originally published: Glendale, Calif.: A. H. Clark Co., 1983.

Reprinted from volume one ... of the original eleven-volume edition

T.p. verso.

Volume I.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-8032-7277-4 (pa: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4962-2556-6 (eBook)

ISBN 978-1-4962-2557-3 (mobi)

1. Women pioneers-West (U.S.)-Biography. 2. West (U.S.)-History.

3. West (U.S.)-Biography. 4. Overland journeys to the Pacific.

5. Frontier and pioneer life-West (U.S.) I. Holmes, Kenneth L.

F59l.C79 1996

978-dc20

95-21200 CIP

Volume 2 introduction by Lillian Schlissel.

ISBN 978-0-8032-7274-3 (pa: alk. paper)

Reprinted from volume two (1983) of the original eleven-volume edition titled Covered Wagon Women: Diaries and Letters from the Western Trails, 1840-1890, published by The Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, California. The pagination has not been changed and no material has been omitted in this Bison Books edition.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Introduction to the Bison Books Edition

Lillian Schlissel

When Ken Holmes began collecting the journals and diaries of overland women, there were few such writings in print. A quarter of a million men and women moved west between 1845 and 1860 knowing they were part of a historic adventure, and there was an outpouring of narratives, but women's observations were not considered significant to the historical process and their writings were largely overlooked.

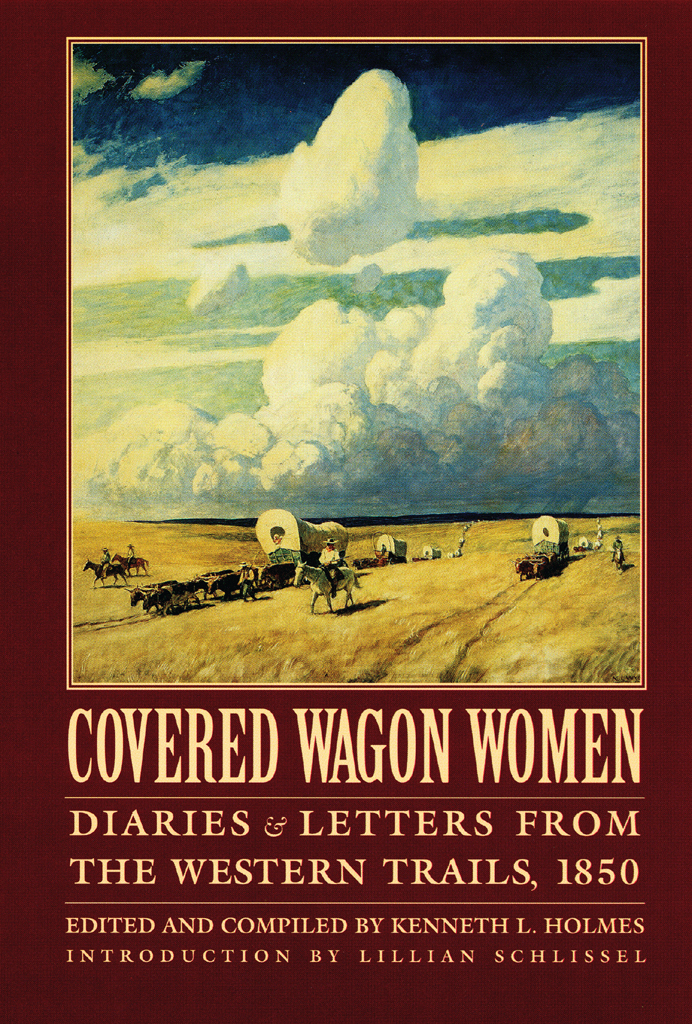

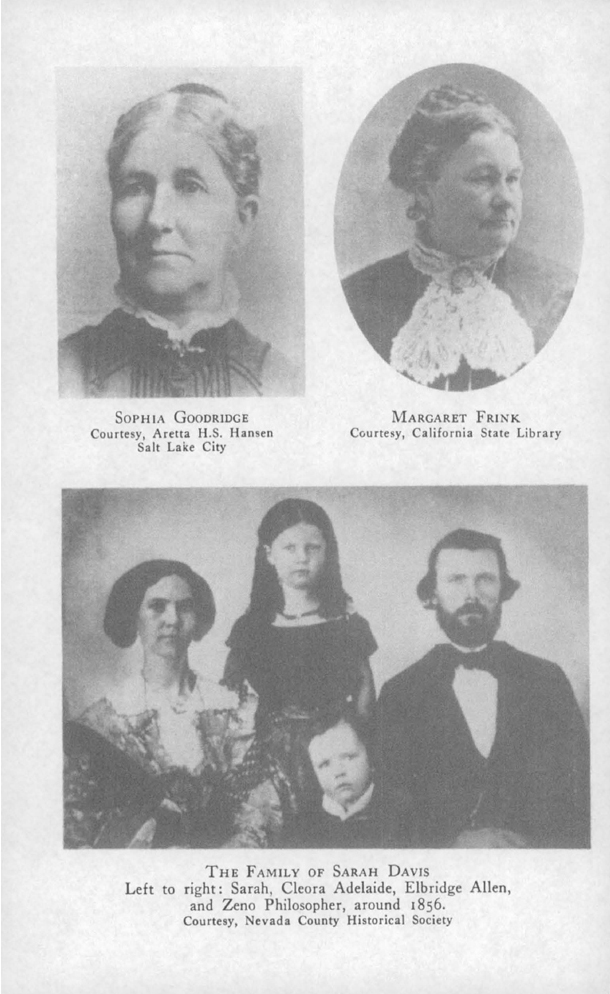

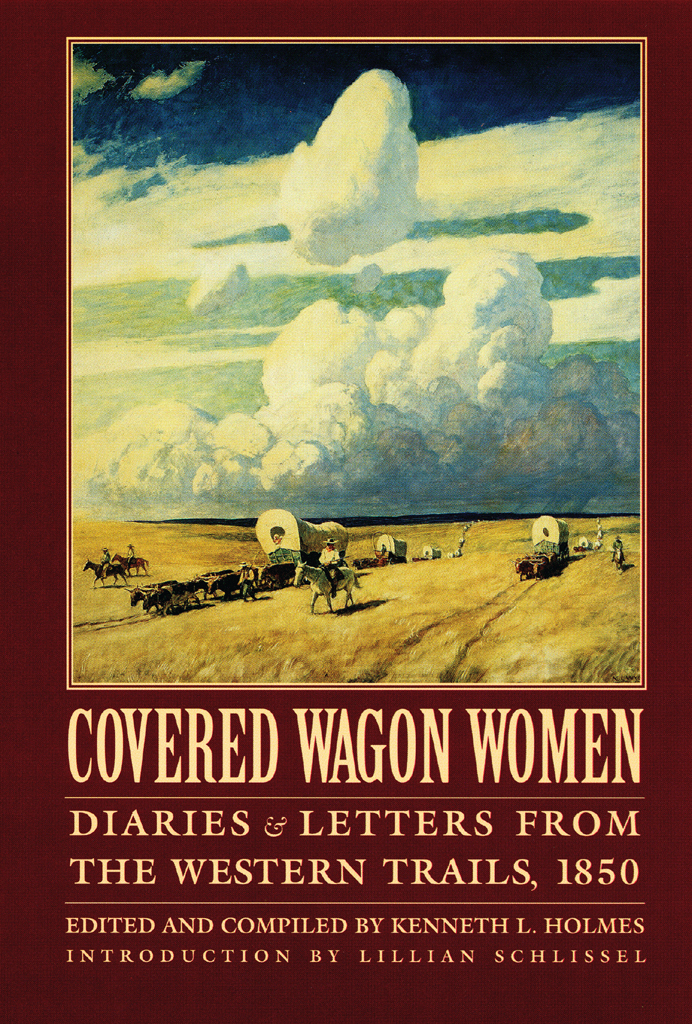

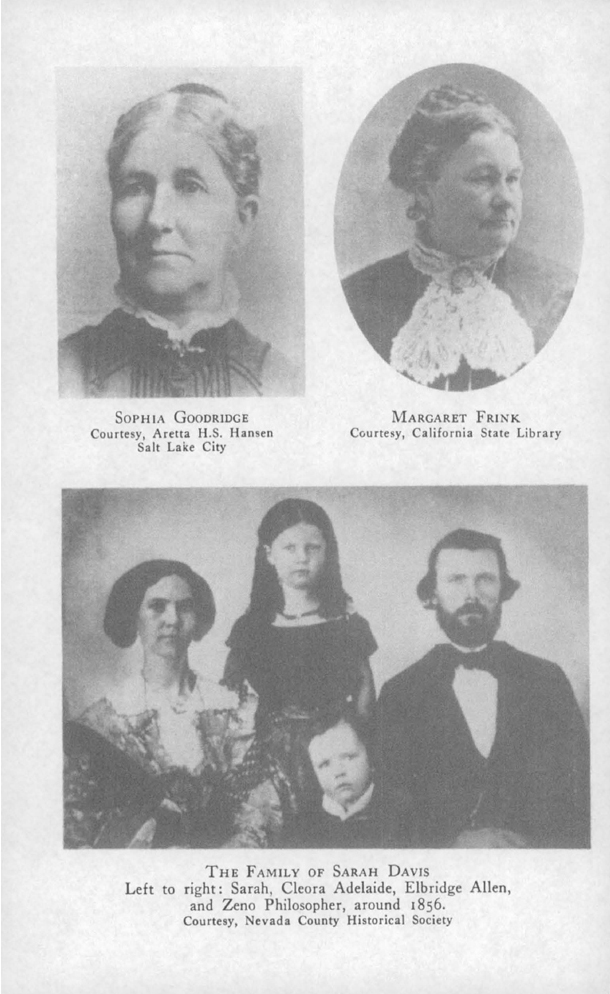

A few historians, though, recognized gems of historical evidence when they found them, and Ken Holmes was one. A diary like Margaret Frink's brought the excitement of a great discovery. This diary, he wrote, is one of the real rarities of historical publication. Holmes loved this project and shared his unabashed pride, telling his readers the thrill he felt when he held the actual book in [his] hands.

And Frink's 1850 diary is certainly one of the best accounts we have of the westward journey. A clear-eyed woman, Frink wrote that she hired a seamstress to make up a fully supply of clothing, but though she might have been well-suited, she and her husband knew nothing of frontier life. She traveled with an india rubber mattress that could be filled with air or water and a feather bed and pillows. She was well provided with plenty of hams and bacon, ... apples, peaches, ... rice, coffee, tea, beans, flour, com-meal, crackers, sea-biscuit, butter, and lard (61), and her husband shipped enough lumber for a house by flatboat down the Wabash and Ohio rivers, down the Mississippi to New Orleans, round Cape Horn and up the coast of South America and found it waiting for them in Sacramento.

During the peak years of 1850-53, the overland journey was a rare spectacle. Margaret Frink wrote, I had never seen so many human beings in all my life before .... in all manner of vehicles and conveyances, on horseback and on foot, all eagerly driving and hurrying forward, I thought, in my excitement, that if one-tenth of these teams and people got ahead of us, there would be nothing left for us in California worth picking up (85-86). Like a demonic driver on a freeway, some careless person ... drove his team up too close behind, and the pole of his wagon ran into [our] stove, smashing and ruining it (97).

That crowded road could also turn treacherous-a safe ford today might be a dangerous one tomorrow, Frink wrote. Our horses could sometimes be in water no more than a foot deep; then, in a moment, they would go down up to their collars as quicksand sucked down both drivers and oxen (91-92). Sometimes nature itself seemed in raw opposition to the travellers: I stood in the sleet and held four horses for two hours, till I thought my feet were frozen (67).

Indians followed the progression of wagons, sometimes from the safety of distance, sometimes at close hand. Frink was careful to name the tribes whose lands she crossed-the Cheyennes, Blackfeet, Snakes, Arapohoes, Oglallah Sioux, Pawnees, and Crows. In June, her wagon party passed a large encampment of Sioux. They were quite friendly. The squaws were much pleased to see the 'white squaw' in our party, as they called me. I had brought a supply of needles and thread, some of which I gave them. We also had some small mirrors in gilt frames, ... with which we could buy fish and fresh buffalo, deer, and antelope meat (94). Social encounters with Indians are often described in women's diaries. Anna Morris, wife of Major Gouverneur Morris, a lady who traveled with her maid, noted that she too visited an Indian house in Kansas. The mistress of the tent spoke french [and] ... was making mockasins (23). A young squaw took a great fancy to my diamond ring (30). Sarah Davis, a young wife traveling with an infant, told that the Indians swarmed a round her wagon train and that their was one Indian come to us for his diner (188). All along the trail, overlanders and Indians negotiated a peaceful commerce. Sophia Goodridge, daughter of a large Mormon family, noted that Aunt Hattie sent a blanket shawl for the special purpose of its being bartered with the Indians. En route, travelers watched attentively while 300 Shoshone warriors with about 1,000 horses were preparing to war with the Cheyennes (230).

These casual observations of Margaret Frink, Anna Morris, Sophia Goodridge, Sarah Davis, and dozens of others provide extraordinary evidence of the ways in which the tribes along the overland route participated in the lives of the travelers. Dozens of diarists note that Indians were usually paid fifty cents a wagon for assisting at river crossings and Indians routinely traded salmon and buffalo with travelers whose supplies were dwindling. Sometimes understanding broke down; it seems clear that tribes expected tribute from people moving through their lands-women wrote of Indians who came begging. Overlanders, for their part, had not the least sense that the land belonged to anyone. But it is also clear that women were not afraid and that they bartered with Indians who moved freely among the wagon trains. The daily exchanges were part of the day's routine, and women wrote to relatives back home to include extra shirts and coffee and trinkets for trade when they prepared for the journey. The women's diaries show that, for better or worse, Indians and overlanders came together out of need and out of curiosity, and that they wove an imperfect understanding each of the other.