Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In Memory of Roger King.

And to Barbara Wilson, with gratitude.

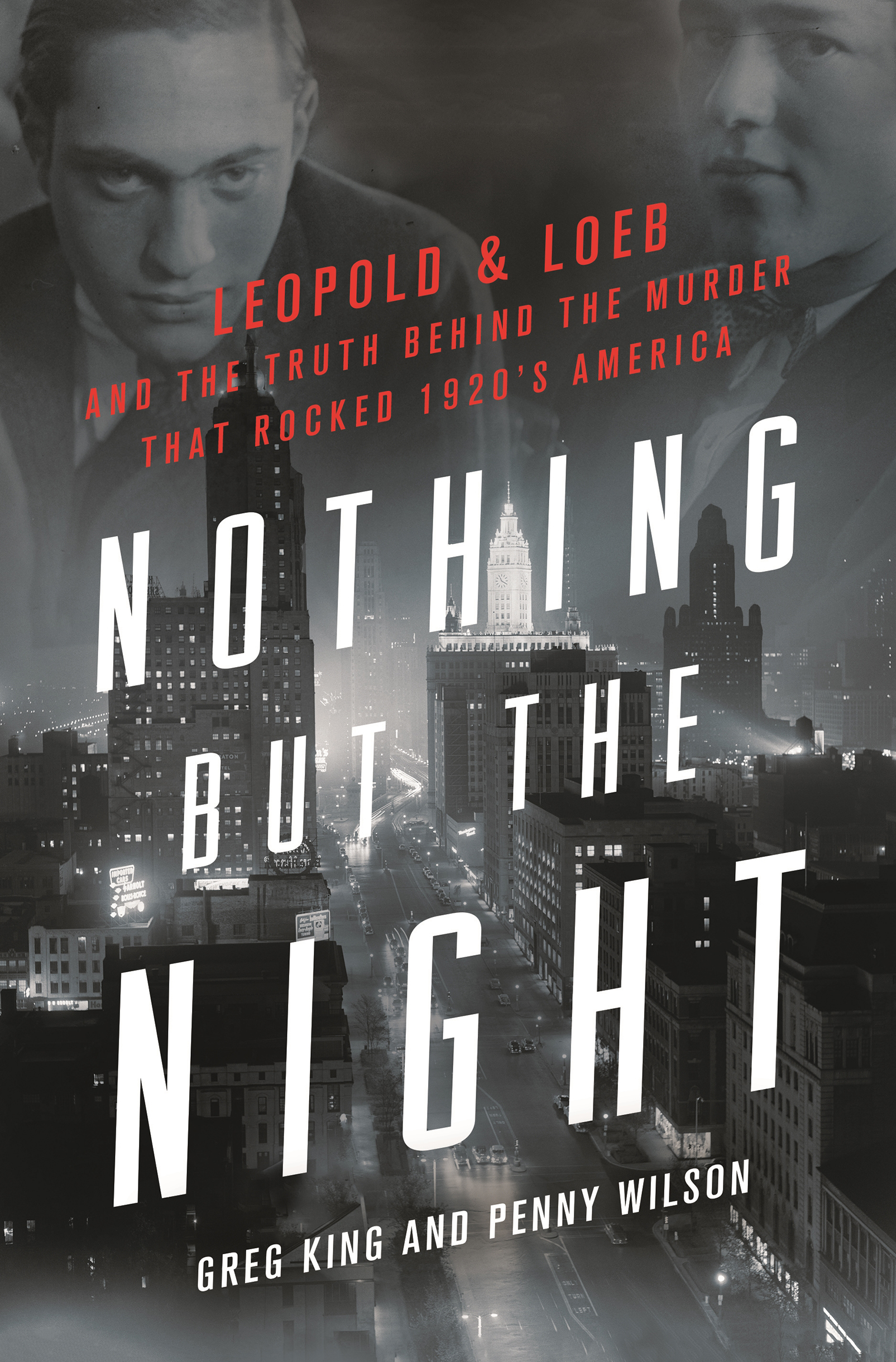

Its been a century since Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two wealthy, Jewish Chicago teenagers, kidnapped and killed fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks. It was the original Crime of the Century. Although other crimes had shocked the nation, the 1924 drama surrounding Leopold and Loeb was among the first to be covered as a nationaleven an internationalmedia event. Newspapers and radio stations fought to report every stray fact, every bizarre assertion. While denouncing interest in the case as prurient, they eagerly printed up the latest gossip, the newest developments, and the most sensational details in efforts to satiate the seemingly unending public appetite for news about the crime and its perpetrators.

From the beginning it seemed so bizarre. Leopold and Loeb were both prodigies, graduating from college by eighteen. Leopolds father was a millionaire box manufacturer; Loebs father, even wealthier, had been vice president of Sears, Roebuck. Their young sons, denied nothing in life, with everything to look forward to and very little to gain, upended expectation by joining together, locked in an amoral danse macabre in which they fed off each other and eventually murdered.

These two disaffected young intellectuals, it is often said, were obsessed with the work of Nietzsche and viewed themselves as supermen. That they had apparently killed just for the experience, to see if they could commit the perfect crime as if it was some kind of childish game pitting their wits against the police, was incomprehensible to Jazz Age Chicago. How had two young sons of wealthy families gone so wrong? The seeming lack of remorse left people reeling as the confessed killers grinned, gave interviews, and gave every appearance that they were enjoying their time in the spotlight. From the start there was an idea that the case offered important lessons. People tried to wrest some moral lesson from the chaos, making the murderers proxies for the clash between traditionalism and hedonism. They were held up as living warnings of juvenile delinquency and intellectual precocity.

Famed lawyer Clarence Darrow managed to save Leopold and Loeb from a date with the hangman, winning them life sentences. In 1936, a fellow inmate murdered Richard Loeb, claiming that he had done so to resist his unwanted sexual advances. This left Nathan Leopold: he rewrote history, blaming his former lover for their crimes and attempting to present himself in the best possible light in his quest for eventual parole. A smuggled straight razor wielded by another fellow convict deprived Loeb of his redemption story; Leopold, by default, claimed the mantle of remorse, won his freedom in 1958, and lived on for another thirteen years.

The case has never quite gone away, even as other more notorious crimes supplanted it in the public imagination. Writing about the case, historian Paula Fass noted that the story has an almost Dostoevskian quality that made it at once compelling and unsolvable. It has spawned films, documentaries, myriad scholarly articles, and a plethora of booksironically the most famous, Compulsion, was a novel, a fictionalized recounting of events in 1924. There have been psychological explorations, historical narratives of varying accuracy, an autobiography by Nathan Leopold and, bizarrely, even two books aimed at a young adult reading audience.

Gallons of ink have been spilled over the case; sometimes the facts seem set in stone. Yet after a century, its time to take a fresh look at the original Crime of the Century, to strip away the legends and challenge accepted history. The Leopold and Loeb case remains relevant today, encompassing as it did so many issues still in headlines: the death penalty; mental illness; anti-Semitism; homophobia; and the corrupting influence of money on the justice system. Darrow delivered an epic closing argument against the death penalty that spared his clients young lives. A century has wrapped it in legend, extolling his brilliant advocacy. In truth, it was dishonest, disjointed, and often offensive.

Then there is the groundbreaking courtroom battle of psychiatric arguments and Freudian theoriesthe first time such testimony took center stage in an effort to transform villains into victims. The wealthy Leopold and Loeb families hired a veritable Whos Who of American psychiatry to examine the pair. Defense alienists proposed a litany of alleged mitigating circumstances: abusive governesses; parental neglect; improper reading materials; and a host of minor physical ailments that, under Darrows careful machinations, skirted the truth. The portraits fell just short of insanity, leaving the popular though erroneous impression that these two young defendants were, at best, emotionally fragile and, at worst, so mentally damaged that they had been unable to resist their murderous compulsions.

Newspapers played up the fact that the Leopolds, the Loebs, and Bobby Frankss family were all Jewish. It didnt matter that the Leopolds were far from observant, that Richard Loebs mother was Catholic, or that the Franks family had converted to Christian Sciencemuch public opinion seems to have lumped them all together. For some, their Jewish roots made them alien: Jewish intellect, it was said, fed the crime, and Jewish money corrupted them and defeated justice.

And, from the first, whispers surrounded the nature of Leopold and Loebs relationship. Even the most sensational newspapers refrained from printing the details, instead merely referring to the pairs perversions. The truth burst forth in stunning testimony during their trial: Nathan was gay, and Richard had gone along with his sexual demands in order to secure him as an accomplice. The issue was deemed so shocking in 1924 that at one point the presiding judge ordered all women from his courtroom, lest details offend their refined sensibilities. It left the distasteful and inaccurate idea that the pair had killed only because of their sexuality.

Or, Darrow and others suggested, it was money that had corrupted their young minds and driven them to murder. Not want of ituntil their incarcerations Leopold and Loeb lived in mansions, drove fast cars, sported the latest fashions, and freely indulged their every desire. Rather, defenders and critics alike claimed, it was this privilege that had so corrupted them and freed them from any sense of social obligation. It was perhaps the earliest example of what became known as the affluenza defense, a strategy echoed in 2013 when sixteen-year-old Texan Ethan Crouch killed four people while driving under the influence and tried to claim that wealth had stripped him of an ability to determine right from wrong.

Here we have tried to answer the remaining questions: Did Leopold and Loeb commit other murders? Who actually killed Bobby Franks? Was he sexually assaulted? Did Nathan have a hand in Richards murder? Here, and often for the first time, we have attempted to address these issues at length, even if much is still speculative. Weve also dug deeply into the psychological relationship between Leopold and Loeb. History (and Leopold) portrayed Loeb as the psychopathic impresario, with Nathan positioned as his weak, infatuated disciple swept up in a mad folie deux. But we discovered evidence contradicting this view. It is time to even out the scales in an attempt to understand what really happened in 1924, even if this introduces a certain imbalance in the narrative.