This book began with an e-mail from an editor at Lyons Press, Stephanie Scott, who sought me out with an idea. Im still not sure why she tapped me over anyone else for this project, but Im extremely grateful for the opportunity and the chance to take it in my own direction. Its been a pleasure working with you, Steph. I must also say thank you to Chris Fusco, editor in chief of the Chicago Sun-Times. Not only did Chris offer support and encouragement, but he opened the doors to the libraries of the Sun-Times and its predecessors, including the Chicago Daily News.

This book could not have happened without the legendary journalists of Chicago, past and present. In particular, I must thank the Chicago Daily News, the Chicago Sun, the Daily Times, and the Chicago Sun-Times. Reading these newspapers rich body of work left me in awe, and it reminded me why journalism is so important. Not only is it a crucial check in a democracy, but it truly is the first draft of historyoffering crucial context and insight to future generations. Many, many thanks for the work done every day by journalists at the Chicago Sun-Times, the Chicago Tribune, and news outlets around the country.

Several people helped me research this book. Id like to say thank you to Elise Fariello of the National Archives at Chicago, John Lupton of the Illinois Supreme Court Historic Preservation Commission, John Reinhardt and Catheryne Popovitch of the Illinois State Archives, Rachel Dailey of the Office of the President of the Cook County Board of Commissioners, Lesley Martin of the Chicago History Museum, and the staff of the archives department of the Clerk of the Circuit Court of Cook County. I also want to thank Dr. Richard Jorgensen, Coroner of DuPage County, as well as the Office of the Clerk of the 18th Judicial Circuit Court. Additionally, I want to thank the staff of the Chicago Public Library and Hassett Commercial Moving and Storage, who accommodated me as I dug through old newspaper clippings.

Special thanks go to Toby Roberts of the Chicago Sun-Times, who answered my many questions and steered me toward valuable resources. I am also grateful for attorney David Sweis and the wise counsel he provided early in this project.

I want to say thank you to additional colleagues at the Chicago Sun-Times. I am grateful to work with Steve Warmbir, the editor who has put up with me for many years. Thank you to Tina Sfondeles, who listened to me talk about this book and even read some chapters. And thank you to Frank Main, Robert Herguth, Paul Saltzman, and Tom McNamee, who gave me advice along the way. Tina, Frank, and Robert are key members of the Sun-Times extraordinary reporting staff. Paul and Tom are veteran editors with invaluable insight.

I must also thank Frank Main for writing a great foreword to this book.

Thanks to Robert Shea for the book he let me borrowand for all the kind words.

To the rest of my Sun-Times colleagues, please know that I am honored to work beside you every day. The same goes for my comrades in the press room of the Everett M. Dirksen US Courthouse.

Finally, thank you to my family. To my parents, for everything; to my in-laws, for giving my daughter the run of their home; and to my wife, who encouraged me to write this book despite the additional strain it placed on our already hectic lives.

Finally, thank you to my daughter. You are my daily reminder of what life is all about.

August Spies is under arrest. He was captured by the police at 8 oclock this morning. The anarchist and incendiary editor of the Arbeiter Zeitungwho was the first one to address the meeting at Desplaines and Randolph streets; who occupied the wagon from which, it is charged, the dynamite bomb was thrown which did such bloody work last night; who was one of the speakers at the mob-meeting on the prairie near McCormicks Monday afternoon; whose words inflamed the mob until it was ready to burn down the great factoryhad the temerity to appear in the editorial rooms of his paper this morning.

~ CHICAGO DAILY NEWS, MAY 5, 1886

CARTER HARRISON III HELD A MATCH STICK BETWEEN HIS FINGERS. HE flicked his wrist.

And in the darkness, its flame illuminated the face of Chicagos mayor.

Standing near the crowd that had gathered at Haymarket Square on Des Plaines between Lake and Randolph, Harrison lit his cigar. He also suspected that, with the sudden burst of light, hed made his presence known to the man standing atop a wagon, speaking to the crowd as rain-clouds gathered overhead.

August Spies.

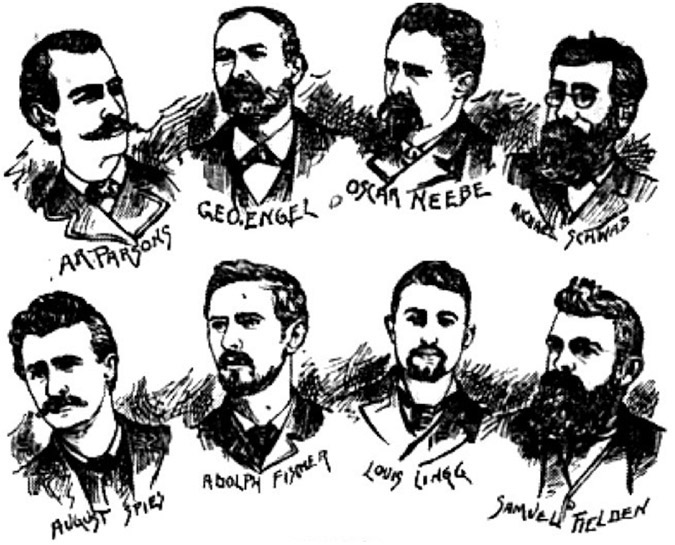

This was May 4, 1886. The day the citys struggle between classes erupted into the bloodiest day of Chicagos history. The day forever tied to Spies, Albert Parsons, Samuel Fielden, Louis Lingg, Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Oscar Neebe, and Michael Schwab.

Illustration of the eight men convicted in the Haymarket trial that appeared in the Chicago Daily News. COURTESY OF SUN-TIMES MEDIA

A day still steeped in controversy over 130 years later.

A half-century had nearly passed since Chicago became a city on the banks of Lake Michigan. Thirty-four years after that, fire ravaged the business district to the south and nearly destroyed all of the citys north division. The fire took 200 lives, left 98,500 people homeless, and cost $190 million in property damage. But a decade after the Great Chicago Fire of October 1871, the city rebuilt with better and handsomer buildings so that scarcely a vestige of the calamity remains, according to the fledgling Chicago Daily News. The population also soon doubled.

Still, trouble brewed in 1886 as members of the citys working class fought for an eight-hour workday. Industrialists called their demand a body blow to the American way of life.

A labor demonstration outside the McCormick Reaper Works turned fatal on May 3 of that year, devolving into bloodshed near Blue Island and Wood. Members of the crowd allegedly turned, with sticks and stones, upon hundreds of non-union workers trying to leave. The demonstrators surrounded the factory. A bullet hit a police officer on duty at the gate. The crowd surged forward.

It took a squad of roughly fifty police officers to break up the riot, in which several people were wounded.

The workers then made their way home with a police escort, still suffering from harassment. A crowd on West 17th Street reportedly grabbed a police officer with a cry of Lets hang the copper! One man found a clothesline and tied it to a lamppost. The officer pulled away just in time to run, dodging gunfire and leaping into a nearby patrol wagon.

That night, following the McCormick riot, a mysterious horseman could be seen dashing over the Randolph Street bridge, then tossing copies of a flyer into a crowd along Lake Street.

No one knew him, the Daily News wrote. Nor could anyone be found who knew whence he came.

The now-infamous circular read as follows:

REVENGE! WORKINGMEN, TO ARMS!!! Your masters sent out their bloodhounds, the police; they killed six of your brothers at McCormicks this afternoon. They killed the poor wretches because they, like you, had the courage to disobey the supreme will of your bosses. They killed them because they dared ask for the shortening of the hours of toil. They killed them to show you, free American citizens, that you must be satisfied and contented with whatever your bosses condescend to allow you, or you will get killed!

You have for years endured the most abject humiliations; you have for years suffered unmeasurable iniquities; you have worked yourself to death; you have endured the pangs of want and hunger; your children you have sacrificed to the factory-lords; in short, you have been miserable and obedient slaves all these years. Why? To satisfy the insatiable greed, to fill the coffers of your lazy, thieving masters! When you ask them now to lessen your burden, they send their bloodhounds out to shoot you, kill you!