Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2009 by Troy Taylor

All rights reserved

Images are courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

First published 2009

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.113.1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taylor, Troy.

Murder and mayhem on Chicagos South Side / Troy Taylor.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-697-8

1. Murder--Illinois--Chicago--History. 2. Crime--Illinois--Chicago--History. I. Title.

HV6534.C4T393 2009

364.1523092277311--dc22

2009010457

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

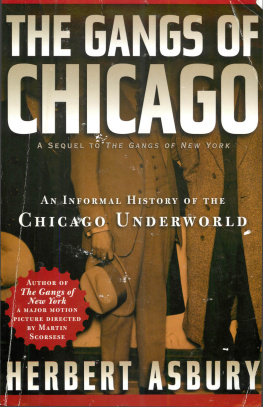

I would like to thank my father for encouraging my interest in Chicago crime and giving me my first biography about Al Capone. Again, thanks to the many writers and chroniclers of crime in the Windy City, especially Herbert Asbury, Jay Robert Nash and Richard Lindberg, and to the kind keepers of libraries, history rooms and archives who always went out of their way to help. Thanks also to Jonathan Simcosky at The History Press and my wife, Haven, for always making sure that I know that nothing is too hard if I put my mind to it.

INTRODUCTION

Nobody planned Chicago. It was not laid out with care. It was carved from the mud, grass and muck along the shores of Lake Michigan and baptized with the blood of the first settlers and soldiers who came to what was then a desolate place. In 1803, those men established a fort called Fort Dearborn that was supposed to provide protection to the brave men and women who tried to build a home out of the wilderness. However, when the War of 1812 unleashed the fury of the Native Americans on the western frontier, Chicago almost ceased to exist before it got the chance to get started. In August 1812, the garrison at Fort Dearborn evacuated its post and, with women and children in tow, attempted to march to safety. But it was overwhelmed and wiped out, in a wave of bloodshed and fire, after traveling less than a mile to what is now the South Side of the city.

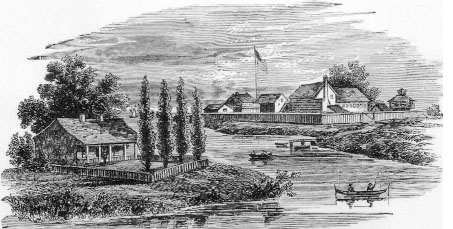

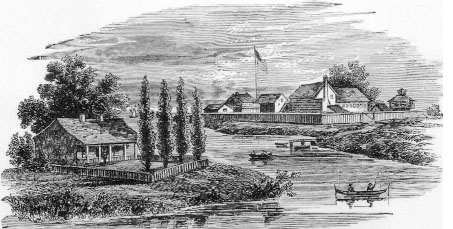

Fort Dearborn, which was originally built by Captain John Whistler, was constructed on a hill that loomed only about eight feet above the Chicago River. It was a simple stockade of logs, inside of which soldiers later built barracks, officers quarters, a guardhouse and a small powder magazine of brick. West of the fort, they constructed a two-story log building to serve as an Indian agency, and between this structure and the fort they placed root cellars and gardens. Blockhouses were added at two corners of the fort and three pieces of light artillery were mounted there. The walls of the fort offered protection to the soldiers garrisoned there, and to the settlers who built homes nearby, but in the end they discovered that the feeling of protection was only an illusion.

An illustration of Fort Dearborn, circa 1803. Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

At the start of the War of 1812, tensions in the wilderness began to rise. British troops came to the American frontier, spreading liquor and discontent among the Indian tribes, especially the Potawatomis, the Wyandots and the Winnebagos. In April 1812, an Indian raid occurred on the Lee farm, near Fort Dearborn, and two men were killed. After that, the fort became a refuge for many of the settlers and a growing cause of unrest for the local Indians. When war was declared that summer and the British captured the American garrison at Mackinac, it was decided that Fort Dearborn could not be held and the fort should be evacuated.

General William Hull, the American commander in the Northwest, issued orders to the forts commander, Captain Nathan Heald, through Indian agent officers. Heald was told that the fort was to be abandoned; arms and ammunition were to be destroyed and all goods distributed to friendly Indians. Hull also sent a message to Fort Wayne, which sent Captain William Wells and a contingent of allied Miami Indians to Fort Dearborn to assist with the evacuation.

There is no dispute about whether General Hull gave the order, nor whether Captain Heald received it, but some have wondered if perhaps Hulls instruction, or his handwriting, was not clear because Heald waited eight days before acting on it. During that time, Heald argued with his officers, with local settlers who opposed the evacuation and with local Indians, one of whom fired a rifle in the commanding officers quarters.

The delay gave the hostile Indians time to gather outside the fort. They assembled there in an almost siege-like state, and Heald realized that he was going to have to bargain with them if the occupants of Fort Dearborn were going to reach Fort Wayne safely. On August 13, all of the blankets, trading items and calico cloth were given out, and Heald held several councils with Indian leaders that his junior officers refused to attend.

Eventually, an agreement was reached that had the Indians providing safe conduct for the soldiers and settlers to Indiana. Part of the agreement was that Heald would leave the arms and ammunition in the fort for the Indians, but his officers refused to do this. Alarmed, they questioned the wisdom of handing out guns and ammunition that could easily be turned against them. Heald reluctantly went along with them, and the extra weapons and ammunition were broken apart and dumped into an abandoned well. Only twenty-five rounds of ammunition were saved for each man. As an added bit of insurance, all of the liquor barrels were smashed and the contents poured into the river during the night.

On August 14, Captain William Wells and his Miami allies arrived at the fort. Wells was a frontier legend among early soldiers and settlers in the Illinois territory. He was also the uncle of Captain Healds wife, Rebekah, and after receiving the request for assistance from General Hull, he had headed straight to Fort Dearborn to aid in the evacuation. But even the arrival of the frontiersman and his loyal Miami warriors would not save the lives of those trapped inside Fort Dearborn.

Throughout the night of August 14, wagons were loaded for travel and the reserve ammunition was distributed. Early the next morning, the procession of soldiers, civilians, women and children left the fort. The infantry soldiers led the way, followed by a caravan of wagons and mounted men. A portion of the Miami men who had accompanied Wells guarded the rear of the column. It was reported that musicians played the dead march, a slow, solemn funeral march that forbode the disaster that followed.

The column of soldiers and settlers was escorted by nearly five hundred Potawatomi Indians. As they marched southward and into a low range of sand hills that separated the beaches of Lake Michigan from the prairie, the Potawatomis moved silently to the right, placing an elevation of sand between themselves and the white men from the fort. This act was carried out with such subtlety that no one noticed it as the column trudged along the shoreline.

Next page