INTRODUCTION

Chicago was created by blood, fire, sin and unbridled perseverance. The early residents came to an unlikely place, a swampy wasteland on the edge of a lake, and began to build a settlement that endured through Indian massacres, fires and civil unrest.

The city was almost destroyed before it even had a chance to begin. The first settlers were wiped out in the midst of the War of 1812, during the Fort Dearborn Massacre. Originally, the fort had offered shelter and protection to those who braved the daunting wilderness, but as tensions among the Native American tribes began to rise at the start of the war, it became clear that the protection the fort offered was merely an illusion. After orders came from the American military command to abandon Fort Dearborn, the commanders reached an uneasy truce with the Indians that would allow them safe passage to Indiana. As a column of soldiers and civilians, including women and children, traveled along the shore of Lake Michigan, however, the Native Americans attacked and killed 148 of the settlers and soldiers. Those who survived but did not escape were tortured throughout the night. Fort Dearborn was burned to the ground but was later rebuilt after the war. By then, more settlers had arrived at what would someday be Chicago, eager to lay claim to a region where no city should have ever been built.

At that time, Chicago was merely a collection of wooden cabins, a place that was of little interest to travelers and new arrivals. A visitor in 1823 noted:

The village presents no cheering prospectit consists of a few huts, inhabited by a miserable race of men, scarcely equal to the Indians from whom they are descended. Their log and bark houses are low, filthy and disgusting, displaying not the least trace of comfort.

Not surprisingly, Chicago grew slowly, and by 1832, it had swelled to a population of only about five hundred souls. In was in this year that the Blackhawk War, an Indian uprising, broke out in Illinois. The existence of Chicago was threatened again, not by Native Americans, but by smallpox.

Hundreds of soldiers arrived in the settlement in the spring of 1832 and found that there was little room, and little food, for the military men and the residents of the community. When General Winfield Scott arrived with hundreds of additional soldiers in July, the situation became even worse because he also brought a smallpox epidemic with him. The Indian peril was quickly forgotten. The townspeople and the newly arrived settlers quickly took flight, emptying Chicago of its civilian population. Only the military men remained, compelled by orders and a sense of duty, and they spent three weeks fighting the epidemic and digging hasty graves for those who died. By autumn, the war had ended, and the soldiers and the smallpox departed. The townspeople returned to their homes, and life in Chicago resumed.

The soldiers who caused so many problems for Chicago were also largely responsible for the citys early growth. The men who had been forced on an excursion through the wilderness of northern Illinois returned to the East with marvelous tales of the areas beauty and of the forests, mill sites and farmland that was waiting for the arrival of settlers. In scores of eastern communities, these reports were heard with great interest, and soon homesteaders began traveling to Illinois and to Chicago.

The first wave of the tide of immigration reached Chicago in the spring of 1833. Most settlers passed through the city on their way to other places, but some, attracted by the citys potential, ended their journey there. Chicago was a city of wooden huts in 1833, with only one frame building, the warehouse of George W. Dole. However, that summer was a time of great activity, and dozens of frame homes and structures were built. They were of flimsy and haphazard construction, to be sure, but their presence provided convincing evidence that civilization was coming to the shores of Lake Michigan. And with civilization came vice.

Even from these early days, Chicago thrived on its reputation for being a wide-open town. The city gained notoriety for its promotion of vice in every shape and form. It embraced the arrival of prostitutes, gamblers, grifters and an outright criminal element. A commercialized form of vice flourished less than two decades later, during the Civil War era, and it is believed that more than one thousand prostitutes roamed the dark evening streets of Chicago. Randolph Street was lined with bordellos, wine rooms and cheap dance halls, and the area became known as Gamblers Row, mostly because a man gambled with his life when braving the streets of this seedy and dangerous district.

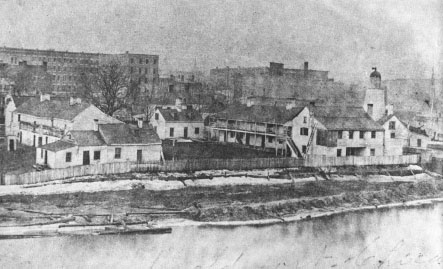

An early view of Chicago shows the second Fort Dearborn, which was constructed before the Civil War. The soldiers from the fort, and those who arrived during the war, played an important role in the creation of organized vice districts in Chicago. Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

Most of the gambling in early Chicago was betting on frequent horse races, which were promoted by prominent settler Jolly Mark Beaubien, and other local sports. There was plenty of friendly card playing going on in taverns and private homes, but there were also a few games conducted by professionals who had drifted into town from St. Louis and eastern cities. Little is known about these cardsharps, but their activities were extensive enough to incur the wrath of the religious element in the community and make them the object of Chicagos first moral reform.

The attempt to drive out the gamblers was led by Reverend Jeremiah Porter, founder of Chicagos first regularly organized church, the First Presbyterian. Reverend Porter lived in New Jersey for many years after leaving the Princeton Theological Seminary and came to the West in late 1831 as chaplain to the garrison at Fort Brady in Michigan. He stayed in Sault Ste. Marie for about a year and a half with great success, managing to stop the dancing to which soldiers and settlers had been accustomed in order to relieve the boredom of the winter months and converting to religion and temperance every person in the fort and settlement except for a young lieutenant and his wife. The couple stayed outside of the fold, despite almost constant prayer and ministering.