Milwaukee Mayhem

MILWAUKEE MAYHEM

Murder and Mystery in the Cream Citys First Century

M ATTHEW J. P RIGGE

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

2015 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

E-book edition 2015

For permission to reuse material from Milwaukee Mayhem (ISBN 978-0-87020-716-7; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-717-4), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

wisconsin history .org

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Designed by Sara DeHaan

17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Prigge, Matthew J.

Milwaukee mayhem : murder and mystery in Milwaukees first century / Matthew J. Prigge.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-716-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-87020-717-4 (ebook : alk. paper) 1. MurderWisconsinMilwaukee. I. Title.

HV6534.M65P75 2015

364.1523097759509034dc23

2015007718

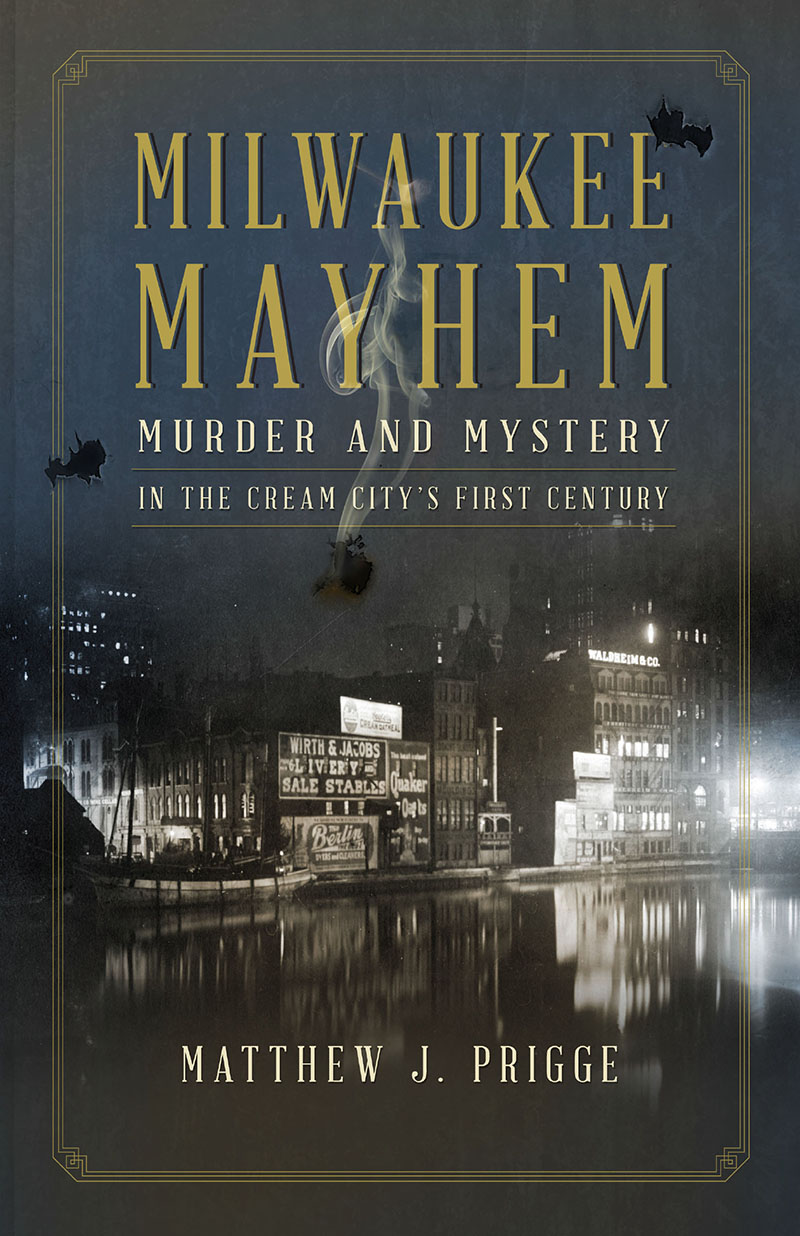

Front cover: WHi 49492, the Milwaukee River at night

Whoever shall record the annals of the circle of States which environ the mighty Lakes of the New World, must occasionally pause from the swelling narrative of a wilderness subdued, of savage and foreign enemies conquered, of Territories and States organized, of the sudden apparition of cities, roads and cultivated fields teeming with population and wealthfrom such and similar signs of an unprecedented material developmentand pause upon some startling outbreak of human passion, which, though a mere eddy in the mighty currentthough only an episode of domestic lifewill often be found no less suggestive of instruction than thrilling with interest.

from Report of the Trial of Mary Ann Wheeler, for the Murder of John M. W. Lace, Her Seducer

Contents

I N THE summer of 1845, the young village of Milwaukee spent several weeks tearing itself apart at its riverway seams. While the village had been incorporated more than five years earlierjoining settlements that had grown along each side of the Milwaukee Riverthe unification was hardly one of spirit or purpose. The most contentious of their disagreements was over the bridges that spanned the waterway. Of the three bridges that crossed the Milwaukee River, those who lived on the west side favored only the one that led down Spring Street, which allowed them access to City Hall and the courthouse. Each of the others were, in their estimation, impediments to river traffic. Those living on the east side preferred the connections that allowed for materials to be unloaded at their lakeside docks and transported across the river by wagon or cart. Westsiders preferred these goods to be unloaded at their river docks, bypassing the east altogether. When a befuddled schooner captain plowed his vessel into the crossing at Spring Street, westsiders accused the east side of paying the captain to cripple their choice passage, revenge for their refusal to help finance the bridges they considered deleterious to their community. Within days, Milwaukees two halves were at war.

It had been more than two hundred years since Father Jacques Marquette became the first European to see the land the village now occupied. He noted in his diary that the place was of no value. Dozens of Europeans visited and traded at the spot over the following decades. The first resident of the area was a Frenchman named La Framboise, whose misdeeds with the locals caused him to be chased out of the area in 1791. The first permanent white resident was Jean Baptiste Mirandeau, who arrived in 1795. His reasons for coming are not known, although some whispered that a scandalous love affair sent him to the young nations hinterlands, while others swore he had taken up the stance of a heretic during his training for the priesthood and fled on the eve of his taking orders. Mirandeau lived east of the Milwaukee River with his Native American wife and large family for nearly a quarter century, trading with local tribes, farming, and operating as a part-time blacksmith. He also might have been Milwaukees first resident inebriate, as he met his fate in the winter of 1819 when he tried to move a heavy log while drunk.

Around the same time Mirandeau was shuffling through the snow toward his dreary end, a six-foot tall, twenty-five-year-old Frenchman named Solomon Juneau was taking over the fur-trading business of Jacques Vieau, who had been swapping with local tribes in the Menomonee Valley since 1795. But it was more than Vieaus pelt trade in which Juneau was interested. He had also become smitten with his fourteen-year-old daughter, Josette. Solomon and Josette were married the next year and in 1822 built a cabin on the east-side stomping grounds of the ill-fated Mirandeau. For more than a decade, Juneau was contented with the simple life of a frontier trader. His primary efforts toward the growth of the settlement were via his dear wife, Josette, who gave birth to seventeen of his children. No one in the area at the time, least of all Juneau, recorded any visions of the place rising to became a major American city. Then the Yankees began to arrive.

Byron Kilbourn was, in the words of historian H. Russell Austin, the most accomplished and learned man to appear in the little backwoods community when he arrived to survey the land west of the Milwaukee River in 1834. He had aristocratic roots and came from an eastern family of means. Kilbourn never intended his career as a surveyor to satisfy his ambitious nature. It was in the course of performing his governmental duties across the river from Juneaus peaceful little outpost that he determined to make himself a city builder. The land west of the waterway, he felt, would prove superior to the swampy patch of earth that Juneau occupied. The Juneau settlement, while having direct access to the lake, was also pinched on three sides between the lake and river. These waterways were almost a noose and, with just the right angling, Kilbourn seemed confident it could be slipped around the neck of the little village, allowing it to hang as his west side birthed a new American metropolis. But Juneau was not one to back down from a fight. For a decade, the earthy, overgrown Frenchman and the refined eastern sharpy built rival villages and competed for the flood of speculation money flowing into the new American west. Juneau called his village Milwaukie; Kilbourn called his Milwaukee. No one knew what the word meant.

Milwaukees population at the time of Kilbourns arrival (excluding Native Americans) totaled about twenty. By the time his wards loyalists took axes to the bridge at Chestnut Street ten years later to avenge the felling of the Spring Street Bridge, nearly nine thousand called the place home. Milwaukees population had tripled in the preceding three years as teams of men swarmed to the place. These were men familiar with hard ways and bone-breaking work. They had set to the west for no more of a reason than to bleed their fortunes from the fertile frontier. As the east ward awoke the morning after Kilbourns west ward made its move on Chestnut Street, they found the bridge reduced to a watery pile of mangled timbers. A mob hustled an old cannon that was being used as a decoration piece to the bank of the river and set its aim upon the home of Byron Kilbourn. Lacking cannonballs, they dismantled a nearby clock, and its round weights were loaded into the muzzle.