Contents

Guide

This book is for Hazel Elelman, my grandmother, with love.

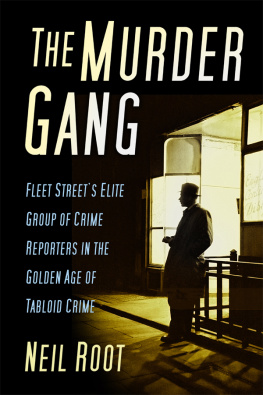

History is the story of the worlds crime.

Voltaire

First published in 2010 by Ian Allan Publishing,

this edition published in 2019 by The History Press

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Simon Read, 2010, 2019

The right of Simon Read to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9157 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

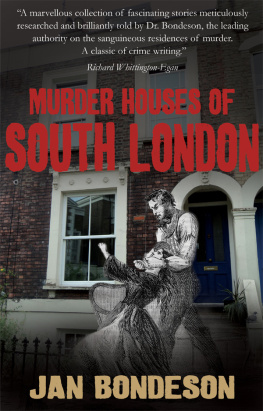

Id like to thank Mark Beynon and the fine people at The History Press for approaching me with the idea for this book and commissioning me to write it. Working on Dark City was great fun, as it gave me a chance to delve once more into my favourite period in history.

My family, as always, was incredibly supportive. I put my father, Bill, to work as a research assistant. Together, we sifted through countless pages of official documents at the National Archives. It presented a special opportunity for my dad, who got to read police reports written by his own father, the arresting detective in the infamous Cleft-Chin Murder case. Im also grateful to my agents Rivers Scott in Britain and Ed Knappman in the United States, and the staff at the National Archives for their assistance. I have to thank Tony, Phil and Mike (as always) for the music.

Finally, love and thanks to my wonderful wife, Katie, who patiently played audience to my manuscript readings and offered advice when I got stuck.

Preface

Christmas shoppers crowded narrow Birchin Lane in the early afternoon hours of Friday, 8 November 1944, their collars turned up against the wet fog that hung heavy over the city. They paid scant attention to the black Vauxhall that turned into the street shortly after 2.30 p.m. and came to a stop outside Frank Wordleys jewellery store at number 23. Three young men, one of them carrying an axe, clambered out of the vehicle and approached the stores front window.

Pearls and diamonds arranged neatly in display cases glittered through the glass. The axe blade smashed the window and littered the pavement in a crystalline shower of broken glass. The men grabbed what they could, as stunned passersby stopped and stared. They hurried back to the car, their arms filled with pearl necklaces and sparkling rings valued at more than 2,000. The engine roared to life and the car peeled away from the pavement. It moved at high speed toward the end of the lane, where the robbers planned to escape via Lombard Street. While frantic pedestrians leapt clear of the vehicle, Captain Ralph Binney a 56-year-old Royal Navy Officer stepped into the street, blocking the cars progress and motioned for the driver to stop.

In the Vauxhall, Binney loomed large in the windscreen, only to disappear when the car slammed into him. The two front wheels rolled over the captain before the car came to a stop. As outraged onlookers ran towards the vehicle, the driver threw the Vauxhall in reverse and backed over Binneys stricken form, but a crowd charging from the rear forced the driver to accelerate forward and run the still-conscious Binney over yet again. This time, the captains coat caught on the cars chassis. The Vauxhall picked up speed and dragged the frantically struggling Binney beneath it.

Horrified onlookers watched helplessly as the car screamed into Lombard Street. From underneath the vehicle, Binney could be heard screaming for help. Another motorist gave chase and followed the thieves over London Bridge and into Tooley Street. As the Vauxhall shot past the terminus for London Bridge Station, Binney was thrown clear of the car, slid across the street and slammed into the kerb. The pursuing motorist stopped to help the stricken man who had been dragged for more than a mile as the thieves car disappeared from view. An ambulance was on scene within minutes and rushed the captain to Guys Hospital, where he died 3 hours later from his extensive injuries. Both his lungs, noted Home Office Pathologist Dr Keith Simpson, who performed the autopsy, had been crushed and penetrated by the ends of broken ribs when the car ran over him.

The Vauxhall was found abandoned not far from where Captain Binney had been thrown free. Scotland Yard launched a massive manhunt, believing the thieves-turned-killers were members of the Elephant Boys, a loosely organised gang of thugs that stamped about the Elephant and Castle area of South London. Detectives scoured the bomb-ravaged neighbourhoods of Bermondsey and other blue-collar enclaves in pursuit of their prey, staking out rough-and-tumble pubs and various hotspots known to be frequented by the areas more shady operators. A break in the case finally came when informants notified police that three men had started keeping a low profile in the wake of the much-publicised crime. They were getaway driver Ronald Hedley, a 26-year-old member of the Elephant Boys, and fellow gang associates Thomas Jenkins and his younger brother Charles Henry Jenkins, known amongst his associates as Harry Boy.

Sent to trial at the Old Bailey in March 1945, Hedley was found guilty of murder, sentenced to hang, but later reprieved; Thomas Jenkins received an eight-year sentence for manslaughter. Harry Boy Jenkins, then 20, went free after witnesses failed to place him at the scene of the crime. He would hang three years later after taking part in another smash-and-grab robbery in which a motorcyclist, following Captain Binneys example, was fatally shot while trying to stop Jenkins and his cohort.

At the end of 1944, noted one crime historian, Captain Binney was an omen of post-war lawlessness. But the case also exemplifies the worst of wartime London.

The lights went out on Thursday, 31 August 1939. The night-time blackout, put into effect three days before the declaration of war, turned Londons once familiar streets into a foreign landscape. Venturing out in the dark became a hazardous undertaking; in the pitch black one never knew when a lamppost or letterbox might cross their path. As the months dragged on, surface air-raid shelters and canvas sandbags became constant obstacles even crossing the street posed a dangerous undertaking.

Buses and taxis manoeuvred blacked-out city streets with their headlamps covered, resulting in more-than-occasional mishaps with pedestrians. By the following autumn, pontoon bridges stretched the Thames and pillboxes lined Victoria Embankment. Children, who had not yet been evacuated overseas or to the countryside, played amongst ruins and searched for shrapnel and other souvenirs of war. Large, zeppelin-shaped barrage balloons hovered above the citys battered skyline.