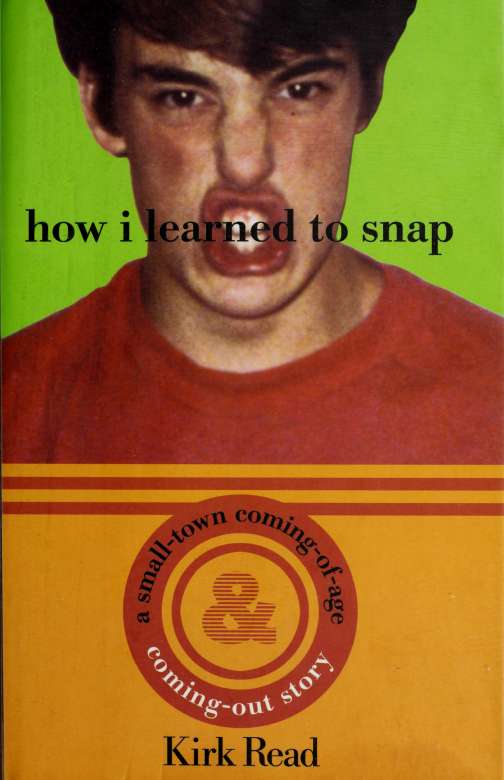

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

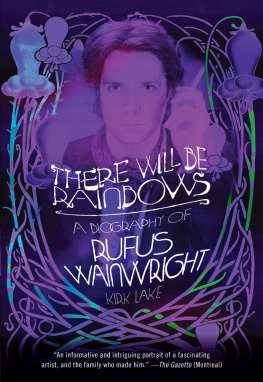

for Richard Labonte

con

acknowledgments 229

yj contents

prologue

Lake County, California, is a lumpy casserole of good country people, leftover hippies, and hardcore druggies. The speed problem here has prompted Senator Barbara Boxer to urge a ten-million-dollar "clean-up" of its meth labs, many of which are situated in Clearlake garages. You haven't lived until you've bowled next to a pack of rednecks on homemade speed. Their prison tattoos and dirty fingernails make me wonder what in the world I'm doing here, why I don't sleep with a gun under my pillow, and why, of all places, I came here to write a book about being openly gay in high school.

The week I traded San Francisco for Lake County, I got a tarot reading from an old-school gay hippie who makes his living from tie-dye. I've historically dismissed tarot readings as the New Age equivalent of kids at a slumber party huddled around a Ouija board, but I thought it would be good trashy fun, and in a county where Wal-Mart and K-Mart are the cultural epicenters, a bit of camp is always welcome.

The tarot queen said there would be a sign. I envisioned earthquakes, floods, and the reawakening of the supposedly dormant Mount Konocti volcano, the imposing stature of which fills the window of my writing studio. "You'll know it when you see it," he assured me.

My sign came in the form of a teenage boy. I'm leery of the word boy being applied to teenagers. The word is so often used in

prologue

the media to portray teenage sex as criminal and horrific. Once you've traded Legos for masturbation, you're not really a boy anymore, are you? But this young man, around fifteen, was undeniably a delicate, peachfuzzy boy.

The ambitiously named Cafe at Wal-Mart was bustling at lunchtime. I was feeling appropriately guilty about my burger and fries, and even worse about spending money at a corporate chain that feeds so much cash to right-wing crazies. This was an East coast lapse in scruples, to be sure.

Amidst those lunching at tiny Formica tables, the boy sat with his mother. He sported a ponytail tied off with a purple scrunchie. His well-conditioned hair hung over the left shoulder of his Calvin Klein tee shirt. I don't think he wanted that ponytail out of his sight, because he kept petting the end of it as if it were a hamster. His fingers were covered with silver rings and he ate quickly, as if some coyote were poised to leap atop the table and finish his tater tots for him. His mother was a round woman dressed in an embroidered Guatemalan shirt I'd seen priced three for a dollar at the Hospice Thrift Shop. He was chubby from sharing his mother's snacks. I wondered how long it would take him to reach her size.

They spoke without looking at one another. I sat at the table behind his mother, catching pieces of their quiet conversation. Names like Pa and Aunt Junebug floated over to me. The boy saw my tee shirttwo baby girls kissing. He looked up from his food to throw glances at me. As he lifted his burger, his pinkies jutted out from the sides of the bun. He was a dainty eater and wiped the sides of his mouth with a small stack of napkins after each bite.

He looked at me again, this time longer. I turned my head so he could get a good look without feeling so self-conscious. When I returned his stare, our eyes locked. I was careful, aware that this was not my turf. In the Castro or Chelsea, such looks are part of the cultural fabric. But I was home again, back in the land of nervous gestures and crude guesswork as to the substance of a stranger's gaze.

VIII

prologue

I went through high school dreaming of being rescued by an as-yet-undiscovered older brother who would adopt me and ask why I looked so sad. I stared at older men I thought might be candidates and was thoroughly heartbroken every time the connection didn't occur the way I'd written it in my journal.

His eyes were full of a need for adoption. I wasn't cruising him. I was gently, carefully letting him know that his tribe was out there, beyond the cinderblocks and hubcaps that filled his front yard. It took me ten years to make it to the other side of this dynamic. How many strangers had I set my eyes upon, begging for reassurance? In that moment, I wished I could have handed him something usefulsomething more than a smile, something more than a soft-eyed stare that said "hang in there" or "save your money."

prologu<

The curtain opened slowly, ian Haisted had just finished

a spot-on piano rendition of Dave Brubeck's "Take Five." It drew polite applause. The gymnasium of Lylburn Downing Middle School was completely dark. When the curtain was drawn, the lights came up on Jesse Fowler, who was standing center stage with his back to the audience. The ominous, pounding strains of Michael Jackson's "Beat It" erupted from the speakers. With each chord, Jesse raised an arm above his head, alternating left and right, just like Michael in the video.

When the drumbeats gently entered the mix, Jesse threw his arms to the side and added his torso to the dance. The guitar roared in, and Jesse spun around on the ball of his right foot. The audience screamed. He was wearing mirrored sunglasses and the kind of red, heavily zippered jacket that Michael Jackson had just introduced to the world. Where had Jesse gotten it? Where had a white boy learned to dance like that?

The black girls were standing by this point, waving their hands in the air. The rest of the audience sat, slackjawed, beholding the purely alien being before them. During Eddie Van Halen's guitar solo, Jesse whipped off his sunglasses and tossed them to the side of the stage. He shuffled his feet, copping moves from the video he'd no doubt watched hundreds of times. But this was

how i learned to snap

more than karaoke footwork. Jesse took ample inspiration, but made the song completely his own.

I was in fourth grade at the time, 1983, sitting on the front row with a broken ankle. Jesse was in seventh grade. His thirteen years made him Moses-size to me. Halfway through the song, Mason Emore leaned over to me and said, "He's a faggot." I cringed, knowing what a horrible thing that must be.

I couldn't take my eyes away from him. Neither could anyone else. Tasha Nelson was dancing in the aisle like she was at a tent revival. Every move Jesse made drew a collective roar. The black girls had moved up to the front and were spinning furiously, six feet beneath his gyrating body. Jesse worked his way across the entire stage, shedding his jacket to reveal a white tee shirt and blue jeans.