Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To our families, and to those in China and elsewhere who helped us shed light while they were compelled to stay in the shadows

This book is the product of five years of reporting in China, the United States, Africa, and other locations, much of it for The Wall Street Journal. Though we reported together, in the majority of cases we traveled and conducted interviews individually. The material from inside Xinjiang, for instance, is the result of reporting Josh did for the Journal in 2017 and 2018, while Liza handled most of the reporting from Hangzhou. Though much of the book benefits from our combined twenty-five years of experience living in and reporting on China, weve tried to keep ourselves out of the story as much as possible. On those rare occasions when we found it necessary to describe observations or interactions from our personal point of view, we have chosen to use the plural pronoun we to avoid the awkward distraction of referring to ourselves individually in the third person.

Throughout the book, we refer far more often to the Communist Party than we do to the Chinese government or China as a whole. Though its membership accounts for a little more than 5 percent of Chinas population, the Communist Party is the ultimate power in the country, standing above both the government and the legal system. It is also the driving force behind the conception, construction, and operation of the Chinese surveillance state.

On rare occasions we have changed names and biographical details to protect sources in China and elsewhere who face possible retribution for having spoken with us.

They took Tahir Hamuts blood first. Next came his voice- and fingerprints. They saved his face for last.

The police officer gestured at a stool set up opposite the camera, and Tahir felt the weariness wash over him. He and his wife, Marhaba, had spent the entire afternoon in that windowless basement, wordlessly waiting their turn at each new station, not daring to ask why they were there. The officers gave away nothing. Each sat behind his or her computer like an irritable robot, issuing instructions in a flat tone tinged with half-hearted menace.

In other parts of China, police often functioned as little more than glorified security guards. Unarmed and undertrained, they could occasionally be found on the streets retreating in exasperation from gaggles of ornery retirees upset at being asked not to monopolize public space. It was different in Xinjiang. Here on the countrys remote western edge, at the doorstep of Central Asia, the police were hard and well armed. Any interaction with them unfolded in an aura of peril and potential violence. The tension was tolerable in short bursts, but to confront it for hours was exhausting.

Tahir lowered himself onto the stool and watched as the officer fiddled with the camera. Instead of one large lens it had three mini-lenses mounted horizontally in a black casing roughly the length and thickness of a small billy club. He had worked as a filmmaker for more than fifteen years and had never seen anything like it.

The officer told Tahir to sit up straight, then adjusted the tripod until the lenses lined up perfectly with the center of his face. The camera was connected by a cable to a computer on the desk opposite him. A woman operating the computer issued instructions in a dull voice. Face the camera. Turn to the right, then all the way back to the left. Then turn back to face the camera. Then look up and down.

Do it slowly, she said. But not too slowly.

Tahir stared into the lens, his back straight and tense. He moved his head to the right, paused briefly, then began moving back to the left.

Stop, the woman said. Too fast. Do it over.

Tahir started again. The officer stopped him again. Too slow this time.

He got it right on the third try. As he moved, the lenses captured waves of light from a fluorescent bulb overhead as they bounced off his skin. The camera converted the waves into streams of ones and zeros that it fed into the computer, where a program transformed them into a mathematical likeness. The program assembled numbers to denote his high nose and dark complexiontraits that typically distinguished Uyghurs like him from Chinas dominant Han ethnic group. It registered his hooded eyes and thin-pressed lips, which he kept frozen in a mask of practiced impassivity. It also spun a series of integers to represent the swept-back salt-and-pepper hair that brushed his shoulders in a rakish manethe type of cosmopolitan flourish that stood out in a hinterland outpost like Urumqi, almost 2,000 miles west of Beijing.

When he was done, the woman told him to open and close his mouth. Tahir stared into the lens and made an O with his lips, like a goldfish gulping water. After he closed his mouth the woman nodded.

You can go.

Feeling dazed, he stood to the side as Marhaba had her turn. She struggled to maintain a consistent speed. With each failed attempt, her frustration grew. It took her six tries. When she was finished, the two climbed the stairs to the lobby of the police station and stepped out past a newly installed security gate into the early Urumqi evening.

In the distance, fading rays of May sunlight glinted off mountain peaks still wrapped in shawls of white snow. This was usually one of the nicest times of year in Xinjiang, a sliver of comfort sandwiched between the regions jagged winters and boiling summers. But the warming weather did little to melt away the chill that enveloped the regions Uyghur neighborhoods.

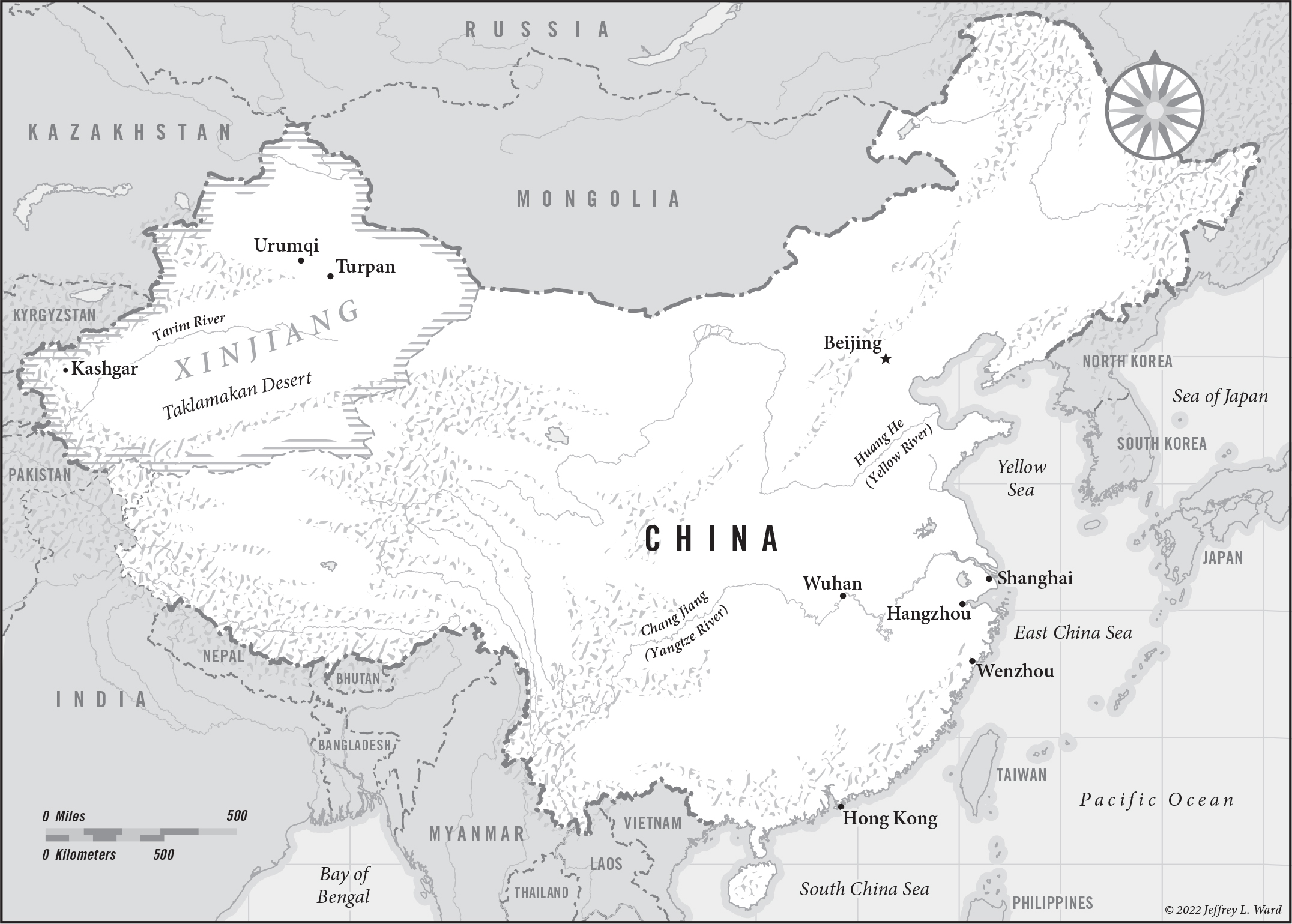

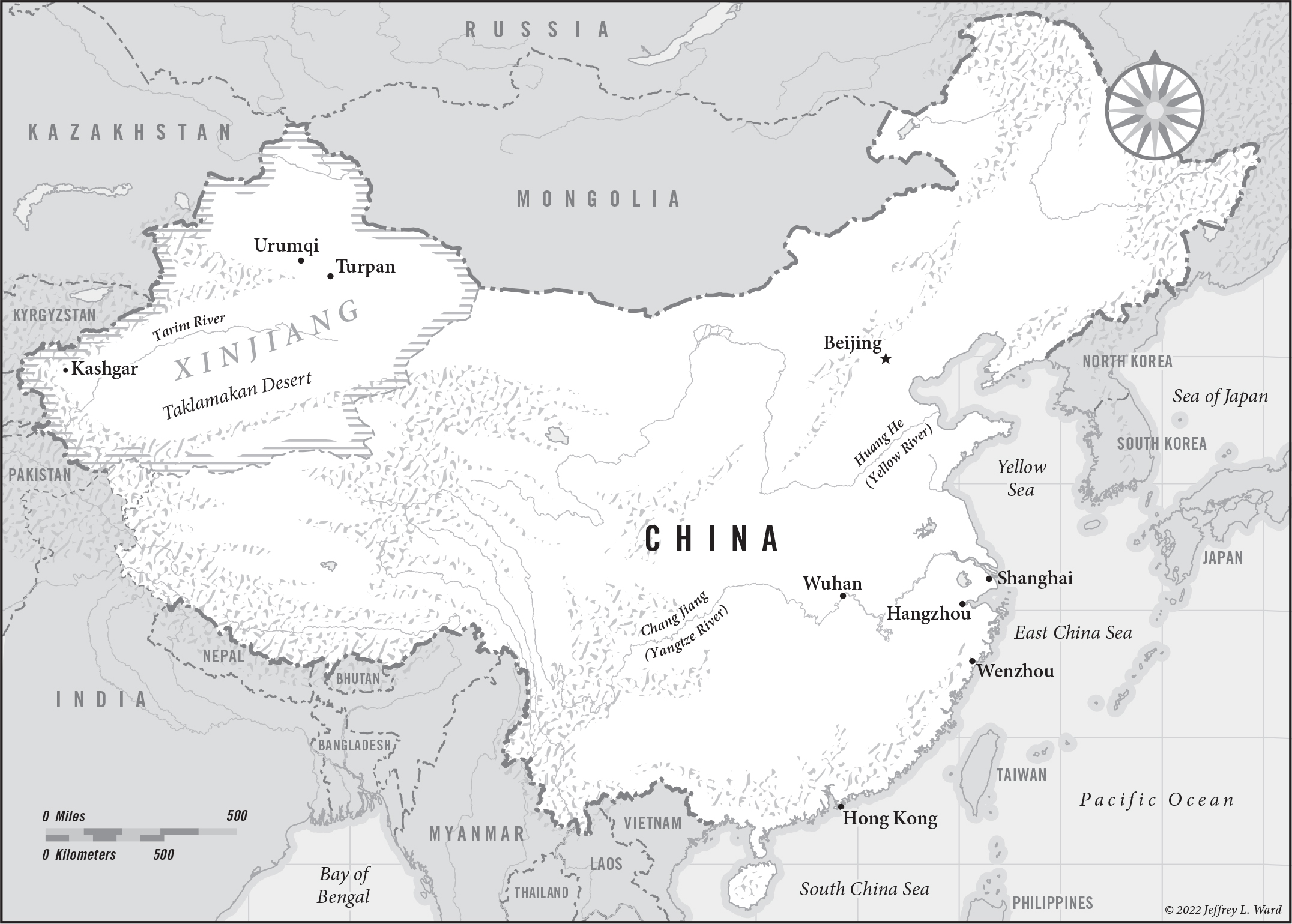

A rugged expanse of mountains, deserts, and steppe twice the size of Texas, Xinjiang has floated on the margins of the Chinese empire for millennia. It formally became a part of China in the late 1800s, when rulers of the last dynasty named it a province, but well more than a century later it still felt like another world. The differences were especially jarring in areas dominated by the Uyghurs, a Turkic Muslim group that traces its roots to the oasis towns dotting Xinjiangs southern deserts. Uyghur enclaves conjured an atmosphere closer to Istanbul than Beijing, with thrumming bazaars, shop signs in Arabic script, and calls to prayer echoing from minaretsexpressions of a distinct identity that Chinas Communist Party wanted to erase.

Six months earlier, Party leaders had set in motion plans to impose an unprecedented level of control in Xinjiang. To aid the effort, local authorities had begun to weave a spiders web of digital sensors across the region that would make it easier for local authorities to monitor Uyghurs and the regions other Turkic minorities. Xinjiang had been crawling with surveillance for years, but the old systems required huge amounts of manual labor. Police could spend weeks scanning video footage or listening to audio recordings just to retrace the movements of a single target. The new systems used artificial intelligence to eliminate human inefficiencies. They could suck in feeds from hundreds of cameras and microphones simultaneously and sift through them to identify targets in a matter of minutes, sometimes even secondsfast enough for security forces to scuttle out and wrap up their prey before it slipped away.