The Party

The Secret World of Chinas Communist Rulers

Richard McGregor

To Kath, Angus and Cate, and in memory of Gwen

Contents

The Red Machine: The Party and the State

China Inc.: The Party and Business

The Keeper of the Files: The Party and Personnel

Why We Fight: The Party and the Gun

The Shanghai Gang: The Party and Corruption

The Emperor is Far Away: The Party and the Regions

Deng Perfects Socialism: The Party and Capitalism

Tombstone: The Party and History

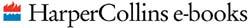

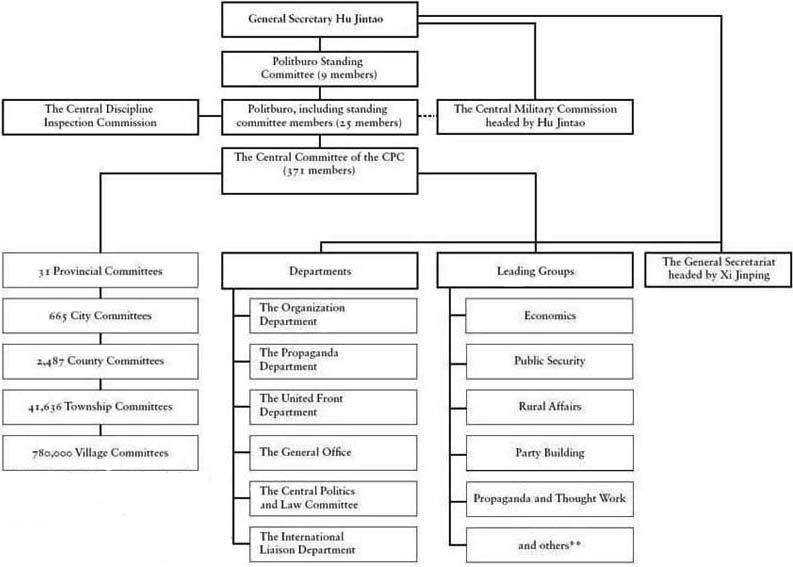

* Party Central is commonly used to refer to the Central Committe of CPC. Therefore, in theory, all the departments at the central level come under the management of the Central Committee. In reality, they all come under the command of the Politburo Standing Committee. Indeed, many of them are directly led by Standing Committee members. ** The other leading groups include the Central Leading Group on Taiwan Affairs, the Central Leading Group on Foreign Affairs and the central Leading Group on National Security.

It was the summer of 2008, one year into the banking crisis in the west. A small group of foreigners, called to China to give financial advice, were ushered into the walled leadership compound astride the Forbidden City in central Beijing. Once in the meeting room, the visitors perched on the edges of the overstuffed armchairs, draped with antimacassars and laid out in a U-shape to create the effect of a space split perfectly down the middle, dividing the visitors from the Chinese. The decorative flowers, the steaming mugs of tea, the warm words of welcome for friends from afarall the ingredients of the time-honoured template for respectful encounters with foreigners were on display.

For the attentive listener, the only part of the meeting that didnt follow the script was their host sitting opposite, Wang Qishan, the vice-premier in charge of Chinas financial sector. Tall, with flat, wide cheekbones and a sharp, imposing manner, the new Politburo member had never been one of those officials whose delphic utterances left interlocutors trying to decipher their meaning afterwards. The Chinese had once used such encounters to solicit foreign views, like bower birds eager to stock up on fresh policy ideas. But Wang quickly made it clear that China had little to learn from the visitors about its financial system. Mr Wang said: This is what you do, and this is what we do, which is what the Chinese always say, one of the participants recalled. But his message was different. It was: You have your way. We have our way. And our way is right!

When China staged its first Davos-style event in 2001, global financiers started travelling there as keenly as they did to the annual conference in the Swiss alps it was styled after. The limousines whisking the financial elite from the airport in tropical Hainan in April 2009 to the seaside conference centre sped through a landscape unlike the usual venues for power meetings in China. The wide, imperious avenues and stiffly guarded marbled buildings of Beijing with their vast entrance portals and stylized meeting rooms were a world away. Unlike the bone-dry northern capital, dusted brown by sands blown in from the nearby desert, the Boao Forum, named after the balmy bay where it is held, was designed to match the message of warm friendship a rising China was determined to convey.

In the early years of the meeting, the courtship had been mutual. Beijing wanted western skills to overhaul their bankrupt state banks. The foreign bankers eyed access to the Chinese market in return. The down payment was delivered in a frenzy of deals in late 2005 and early 2006, when foreign financial institutions invested tens of billions of dollars in Chinese state lenders. The money came with a promise from the foreigners to the laggard locals to teach them the secrets of risk management and financial innovation. The western banks approached the exercise almost as adult education, which is why what happened subsequently was so shocking.

Barely two years after the big Chinese banking deals, the humbled Visigoths of global finance were back. This time, battered by the unfolding credit crisis, they returned, humiliated, cap-in-hand, seeking Chinese cash to shore up their balance sheets or selling their newly acquired shares to take money home. Rather than displaying their wares in Boao and Beijing, the bankers and their advisers slunk in and out of town with barely a peep. One by one, at the 2009 Boao forum, senior Chinese officials tossed aside the soothing messages of past conferences to drive this reversal of fortune home. The first, a financial regulator, lambasted a recent meeting of global leaders as lip service. Another tore into the role of international ratings agencies in the financial crisis. A retired Politburo member ominously suggested the US needed to make sure it protected the interests of Asian countries if it wanted China to keep buying its debt.

When it was his turn at the mike at the session in the resorts Oriental Room, the man anointed as the global face of China Inc. dropped his polite faade as well. Lou Jiwei, as the first head of the China Investment Corporation, the countrys sovereign wealth fund, had been careful to project a conciliatory image since the bodys establishment in 2007. The first difficult years in the job had slowly soured Lous good cheer. The funds bold initial investments offshore had lost money, attracting vitriolic criticism at home. Abroad, Lou became bitter at the opposition he faced to investing in the US and Germany.

Lou recounted to the Boao dignitaries how a delegation from the European Union had demanded after the funds establishment that he cap any stakes he bought in their companies and not ask for voting rights in return for shares purchased. Lou reckoned he was lucky in retrospect to meet such patronizing intransigence, because he would have lost a ton of money if he had been allowed into the market. So, I want to thank these financial protectionists, because, as a result, we didnt invest a single cent in Europe. Now, he noted sardonically, to a mixture of stifled guffaws and startled gasps in the audience, Europeans had sheepishly returned to tell him his money was welcome, with no strings attached. People suddenly think we are lovable.

The same mood of brittle triumphalism on display at Boao had begun to course through government pronouncements, official debates, the state media and bilateral meetings at home and abroad from early 2009. Behind the scenes, in ways not easily visible from the outside, the official propaganda machine had clicked into overdrive as well. The Peoples Daily , the mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, usually reserved its front page for the daily diaries of top leaders, their foreign guests and the latest political campaigns. The paper, which acts as a kind of internal bulletin board for officials, relegated finance stories to the back pages, if they were reported at all. The announcement in March 2009 of healthy profits by the big Chinese banks, once derided in the west as financial zombies, made for an irresistible exception. The banner headline on the papers front page screamed: Chinas Banking System Hands in a Fabulous Exam PaperStands out After Being Tested by the International Financial Storm.

For a decade, Beijing had resisted pressure from Washington, led latterly by the former Goldman Sachs boss, Hank Paulson, as Treasury Secretary, for wholesale financial liberalization. In the seven years to 2008, the Chinese economy had more than tripled in size. But alongside Chinas rise, the patience with which Beijing listened to advice from foreigners had been dwindling. It wasnt until the western financial crisis that the confidence of the likes of Wang Qishan spread through the system and burst to the surface like never before. Many Chinese leaders were beginning to voice out loud the sentiments expressed privately by Wang: what on earth have we to learn from the west?