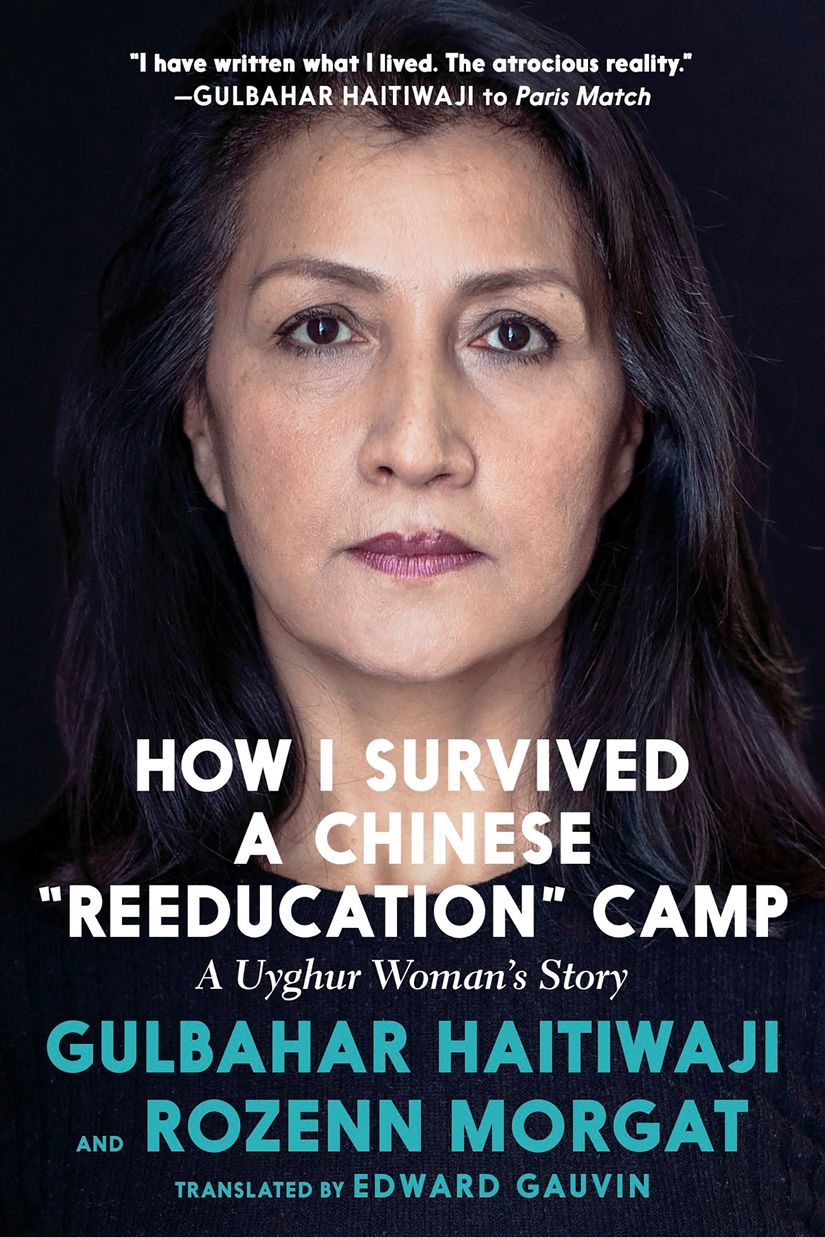

HOW I

SURVIVED

A CHINESE

REEDUCATION

CAMP

A UYGHUR WOMANS STORY

Gulbahar Haitiwaji

Rozenn Morgat

Translated by Edward Gauvin

SEVEN STORIES PRESS

New York Oakland

Copyright 2021 by Gulbahar Haitiwaji and Rozenn Morgat

English translation 2022 by Edward Gauvin

Published by Seven Stories Press, Inc., by arrangement with ditions des quateurs,

Paris, France.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

sevenstories.com

College professors and high school and middle school teachers

may order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles.

Visit https://www.sevenstories.com/pg/resources-academics

or email academics@sevenstories.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file.

isbn: 978-1-64421-148-9 (hardcover)

isbn: 978-1-64421-149-6 (ebook)

Printed in the USA.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

To all those who didnt make it out.

To Fanny, Gatane, and Lucile

free women.

Through vocational training, most trainees have been able to reflect on their mistakes and see clearly the essence and harm of terrorism and religious extremism. They have notably enhanced national consciousness, civil awareness, awareness of the rule of law, and the sense of community of the Chinese nation. They have also been able to better tell right from wrong and resist the infiltration of extremist thought.... They are confident about the future.

SHOHRAT ZAKIR, chairman of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and the Communist deputy party chief of Xinjiang, to state media on October 16, 2018

Not any force can stop Xinjiang from moving towards stability, development, and prosperity.

SHOHRAT ZAKIR, during a press conference held by the State Council Information Office on December 9, 2019

Referring to the Chinese reeducation camps in Xinjiang.

Preface

Gulbahar survived internment. She endured hundreds of hours of interrogation, torture, malnutrition, police violence, and brainwashing. On the basis of a photo of her daughter taken during a Uyghur diaspora demonstration in Paris, China sentenced Gulbahar to seven years in a reeducation camp. Her trial did not take place until after a year in detention. It lasted all of nine minutes. Neither a judge nor lawyers were present. Gulbahar stood all alone in the dock, facing three police officers. For a long time, she was sure she would simply be executed. Then she was overcome by another certainty: she would die in a Xinjiang prison camp. No onenot the nation of France, where she had lived in exile for the last decade, nor her daughters and husband, Gulhumar, Gulnigar, and Kerim, all three of them political asyleeswould be able to come to her rescue. She could feel the trap that China had set closing around her once and for all.

After her release, deep in her heart, Gulbahar was riven by conflict: should she go public and tell the world her story, or remain in the shadows to protect her loved ones? During our conversations in her Boulogne apartment, she seemed cautious, resigned to keeping her true identity a secret.

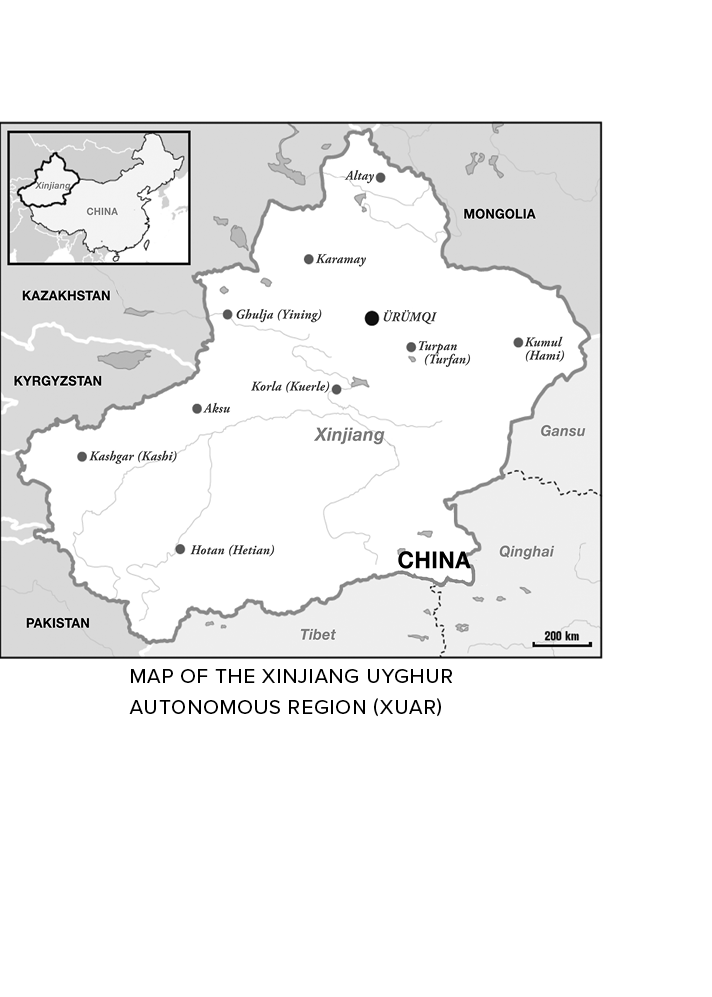

Gulbahar was born into a Uyghur family that had lived in Xinjiang for generations. Like her ancestors, she was raised in that oil-rich land of deserts and oases, for centuries troubled by deep-seated geopolitical conflicts that hadapart from brief bursts of independenceresulted in long periods of Chinese annexation. The arrival of the Communists in 1955 led to the province becoming part of the Peoples Republic of China and being renamed the Xinjiang Autonomous Region: Xinjiang means new frontier in Mandarin. Since then, this vast territory, more than twice the size of Texas and six times the size of the United Kingdom, has suffered from colonization at the hands of Chinas ethnic majority, the Hans. Over time, oil refineries developed, Chinese tractors paved the way for sprawling cities, and Communist red overran the land with countless banners, flags, and paper lanterns; from minor intrusions to large-scale discrimination, Uyghurs were subjected to the first manifestations of what is now clearly full-scale genocide. One day in May 2006, exhausted from seeing their prospects for the future dwindle before their very eyes, Gulbahar and her family left to start a new life in France.

Because Uyghurs are Sunni Muslims and their culture has Turkic rather than Chinese roots, and because China was late in absorbing them, the ethnicitys minority separatist fringe flies the sky-blue flag of East Turkestan for independence. In 2009, the rmqi riots, which claimed the lives of several hundred Hans and Uyghurs, were met with repressive measures of unprecedented violence. The powers that be had at their disposal an impressive arsenal of means for surveillance and control: armies of cameras that used facial recognition, police presence on every street corner, and from 2017 onwards, transformation-through-education camps. At the same time, the region became the most highly surveilled place in the world and a centerpiece of Xi Jinpings New Silk Road, or Belt and Road Initiative. A gateway to Central Asia, Xinjiang borders on eight different countries. It has become a strategic linchpin for the colossal infrastructure project aimed at connecting China to Europe. This is far from mere coincidence. To date, Amnesty International and the Human Rights Watch estimate that more than one million Uyghurs have been sent to or are currently interned in these camps that China persists in designating as schools, where teachers claim to eradicate Islamist terrorism from Uyghur minds.

Gulbahar has never harbored the slightest interest in her countrys politics. She admits as much without contempt, and with even a hint of pride: when she speaks of her religion, she speaks of a peaceful Islam, a moderate Islam. She is neither a separatist nor an Islamist terrorist. And yet she was sent to a camp. Herein lies the hypocrisy and perversity of the Chinese concentration camp system, which seeks not to punish an extremist Uyghur minority, but instead to eradicate an entire ethnicity, right down to its members living in exile abroad, like Gulbahar.

One morning in November 2016, Gulbahar received a mysterious phone call from Xinjiang. An employee of her former company was requesting that she return to China. For administrative formalities, he specified, documents concerning your forthcoming pension. Gulbahar was wary, but not wary enough. A few days later, she landed in rmqi , and her ordeal began: authorities confiscated her passport, threw her in jail, and then, after months in a cell without a trial, she was transported to a camp.

In the camps, the reeducation process is systematic in that it applies the same remorseless method to destroying all its victims. It starts out by stripping them of their individuality. It takes away your name, your clothes, your hair. There is nothing now to distinguish you from anyone else. Then the process takes over your body by subjecting it to a hellish routine: being forced by teachers to unendingly recite the glories of the Communist Party for eleven hours a day in a windowless classroom. Falter, and you are punished. So you keep on saying the same things over and over again until you cant feel, cant think anymore. You lose all sense of time: first the hours, then the days.