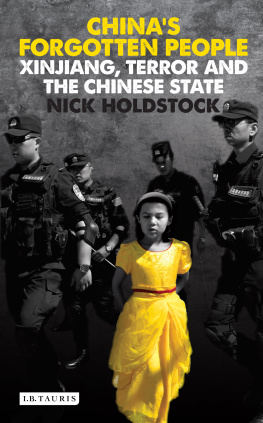

There has been a significant increase in the twenty-first century in the frequency and intensity of violent incidents in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the far north-west province of China, where the Uyghurs, the Turkic-speaking Muslim people who historically constituted the majority population, feel themselves displaced and discriminated against by the growing in-migration of Han Chinese. The book explores the continuing unrest in Xinjiang. It focuses in particular on the major violence of July 2009 in the city of Urumqi, on repression and the practice of Islam in southern Xinjiang, and on the policy of the Chinese Communist Party which has used the rhetoric of the War on Terror to justify its repression in terms which it hopes will gain sympathy from the international community. The book relates these particular points to the development of China-Uyghur relations more broadly in the longer historical perspective and concludes by discussing how the situation is likely to unfold in the future.

Routledge Contemporary China Series

Urbanisation, Regional Development and Governance in China

Jianfa Shen

Midwifery in China

Ngai Fen Cheung and Rosemary Mander

Chinas Virtual Monopoly of Rare Earth Elements

Economic, Technological and Strategic Implications

Roland Howanietz

Chinas Regions in an Era of Globalisation

Tim Summers

Chinas Climate-Energy Policy

Domestic and International Impacts

Edited by Akihisa Mori

Western Bankers in China

Institutional change and corporate governance

Jane Nolan

Xinjiang in the Twenty-First Century

Islam, Ethnicity and Resistance

Michael Dillon

China Studies in the Philippines

Intellectual Paths and the Formation of a Field

Edited by Tina S. Clemente and Chih-yu Shih

For more information about this series, please visit: www.routledge.com/Routledge-Contemporary-China-Series/book-series/SE0768

Xinjiang in the Twenty-First Century

Islam, Ethnicity and Resistance

Michael Dillon

First published 2019

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2019 Michael Dillon

The right of Michael Dillon to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-1-138-81105-8 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-74934-1 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Contents

PART 1

Deep roots of the Xinjiang conflict

PART 2

Urumqi, Kashgar, Khotan: 200915

PART 3

Conflict and resolution in Xinjiang: the Xi Jinping era

Guide

All photographs were taken by the author.

At the time of writing, Xinjiang, which has already endured decades of repression, is subject to the most draconian policies of policing and social control it has yet experienced. This insidious but highly effective subjugation of the Uyghur people of Xinjiang, in the name of a continuing War on Terror, has been largely unreported by the Western media which tends to respond to dramatic violent incidents. I hope that this book contributes to raising awareness of the desperate position in which the Uyghurs find themselves, as well as offering an analysis of how this situation has arisen and how it could be resolved.

The main argument of the book is outlined in the Introduction. , I have analysed the conflict and in the final chapter have offered tentative although pessimistic suggestions for a resolution. This has necessitated repeating some of the details of the various outbreaks of violence but as a result the sections should be sufficiently coherent to be read independently. The Postscript includes the latest information from Xinjiang at the time of writing.

It has always been necessary to exercise caution in naming those in Xinjiang who have provided information or otherwise assisted in my research, for fear of serious repercussions on their careers if not their liberty. The increased repression in the region at the time of writing has made this caution more essential than ever. Suffice it to say that without practical assistance and support from many individuals, mostly Uyghurs, inside Xinjiang it would not have been possible for me to carry out this work. Outside Xinjiang, my work on this book has been informed by contributions made by numerous academic colleagues to international conferences, particularly those organised by The George Washington University and the Universit Libre de Brussels in Washington and Brussels. For eyewitness evidence from Kashgar I am grateful to the film maker and photojournalist, Andreas Rassos. I am grateful to the editor of Central Asian Affairs , Marlene Laruelle, not only for organising those conferences but also for permission to use material in that first appeared in Kashgar and Khotan since 2010: Islam, ethnicity and traditional Uyghur culture in southern Xinjiang in Central Asian Affairs 2015.

At Routledge I have, as always, appreciated the support and encouragement of Peter Sowden who is responsible for publishing a growing series of important books on Xinjiang. I am also grateful for the helpful comments of copy editors.

Michael Dillon

Worksop, Nottinghamshire, August 2018

Note on Spellings

For Chinese names, the Hanyu pinyin system has been used throughout. There is no universally accepted way of romanising personal and place names in the Uyghur language which is written mainly in a variant of the Arabic script but also appears at times in Latin or Cyrillic script. I have used the simplest and least confusing form available: where Uyghur personal names have been taken from Chinese texts, it has sometimes only been possible to cite them in pinyin romanisation. Places in Xinjiang usually have both Uyghur and Chinese names; some also have a Mongolian version. I have chosen the most commonly used forms, with some preference for the Uyghur name, while indicating the alternatives.