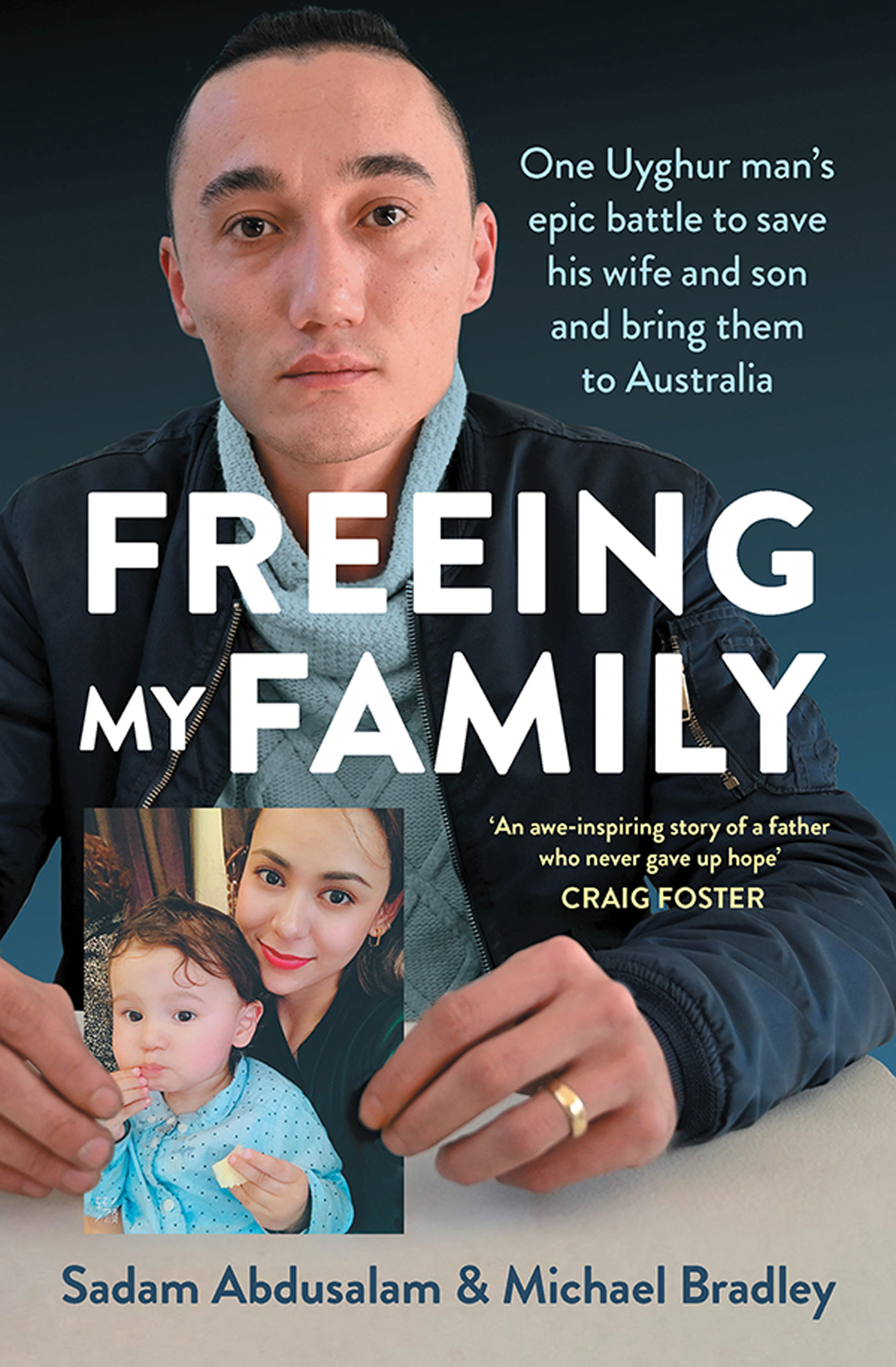

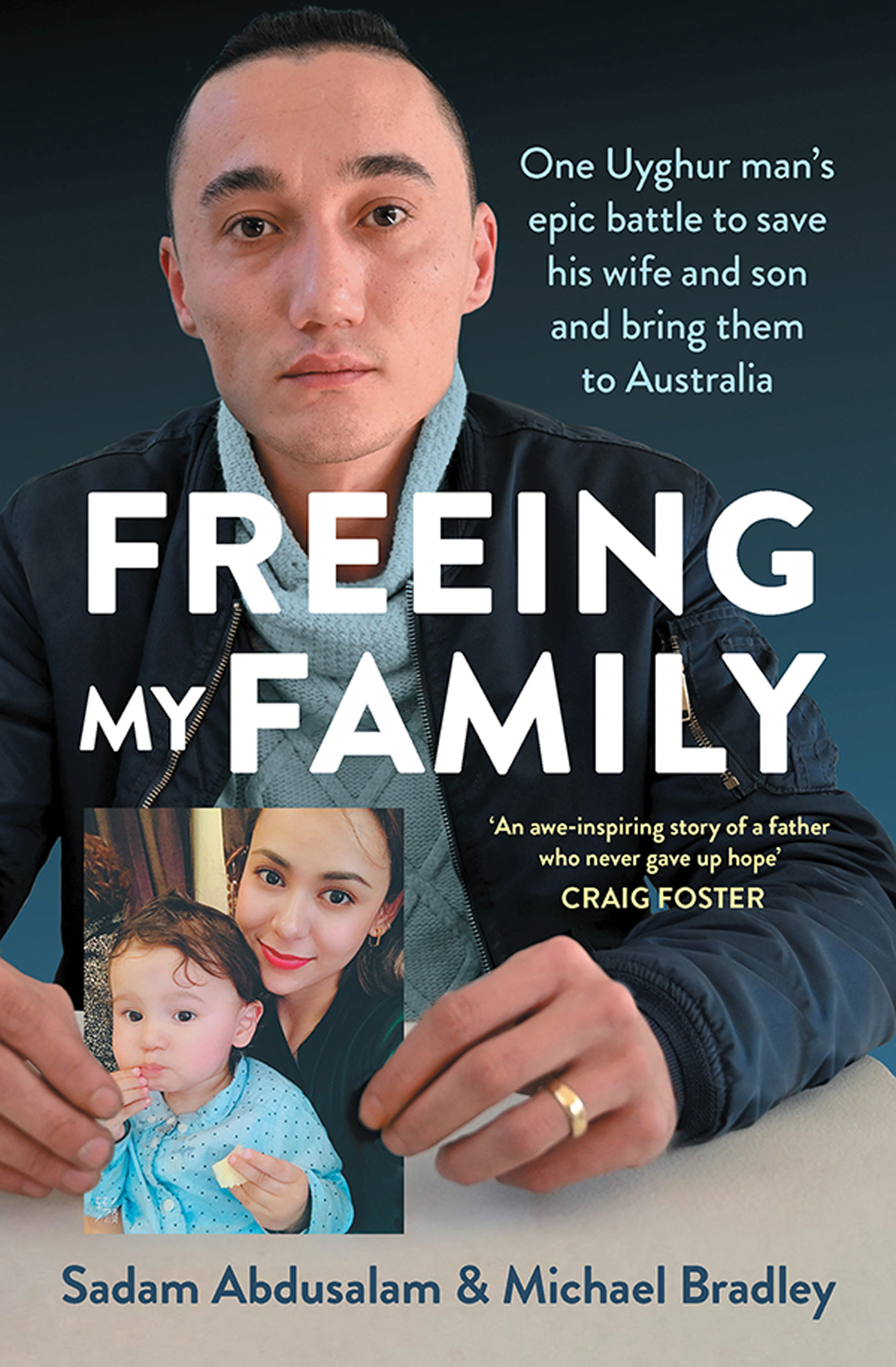

Sadam Abdusalam is an Australian of Uyghur background. Michael Bradley is the head of Marque Lawyers, the legal firm that took on Sadams case pro bono. Michaels articles have been published in Crikey, The Saturday Paper, The Australian Financial Review, ABC Online and The Sydney Morning Herald.

An awe-inspiring story of a father who never gave up hope of rescuing his wife and son from a genocidal regime.

Craig Foster AM, former Socceroos captain and author of Fighting for Hakeem

Against all odds, Sadam achieved the impossiblegetting his wife and son out of Chinas Xinjiang region in the midst of the Chinese governments brutal crackdown against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims. This book gives a raw insight into the painstaking hard work and persistence it took for Sadam and Michael to navigate Australian law, bureaucracy, politics and the media to bring Nadila and Lutfi to freedom.

Elaine Pearson, Human Rights Watch, author of Chasing Wrongs and Rights

Other books by Michael Bradley

Coniston

System Failure: The silencing of rape survivors

First published in 2022

Copyright Sadam Abdusalam and Michael Bradley 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Cammeraygal Country

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Allen & Unwin acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the Country on which we live and work. We pay our respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, past and present.

ISBN 978 1 76106 540 8

eISBN 978 1 76118 505 2

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Lisa White

Front cover photograph: Peter Parks/AFP via Getty Images

For Lutfi

Love is the bridge between you and everything.

RUMI

Sadam was next to me, pulsing. Over the two and a half years since wed first met, his nervous energy had been a constant, visceral reminder of what was at stake for him. He wore the stress on his face, in his body and in his words. His life was singular.

As a lawyer you encounter people at the extreme often enough. Not in the way that doctors or nurses do, dealing with literal life and death, but plenty of times at the lowest depths of despair and the highest peaks of unrealisable expectations. Its easy, and necessary, to place a professional distance between your clients disasters and yourself. Your function is precisely defined, and it does not include a requirement to care.

Of course, you couldnt not care about Sadam. Anybody would be moved by his predicament and wish for the obvious happy ending to his troubles. But caring and feeling are different things, and Sadam had got under my skin; the first client in my 30 years as a lawyer to achieve that. It wasnt the romance of his story; it was him.

The Qantas domestic terminal was mostly deserted, interstate travel still being heavily restricted due to the pandemic. I had found Sadam outside the security check-in, clutching an enormous bunch of flowers and a remote-control car he was hoping would break the ice with the son he had never met. He looked terrified, and relieved to see me.

We sat down in the gate lounge to wait the half hour or so before the planes expected arrival. It was due on time, 11.45 a.m. Thursday, 10 December 2020.

Sadams English is excellent, but hes shy about it and not a man of many words. Im so nervous, Michael was about all he could manage now, over and over again. I, also not famous for small talk, did my best to keep chatting inanely about flight paths, the weather, how exciting this was, how wed celebrate when it was over. It was a long half hour; the years of waiting felt squashed into the tight space we occupied, claustrophobic despite the cavernously empty surrounds.

I thought he might implode. It had been too much; this was too much. Sadams pure focus on making this moment happen was now approaching its end point, and he was vibrating with an intensity that was almost scaring me. Almost. Not quite. I kept on talking.

Through the window we could see the plane pull into its gate. Theyre in there, mate, I said to Sadam. He was beyond talking at this point, just shaking.

I told him to text Nadila and get her to wait, to be the last to leave the plane. I figured itd be so much nicer for the family to have their moment of reunion in an empty space, not surrounded by business travellers in a hurry to get to their meetings. So we waited as the plane emptied, then a beat. Im not really into cinematic moments, but time did stop.

And then it happened, and if I could have turned on the slow-motion function I would have. We saw Nadila first, Lutfi behind her legs. Sadam was off, running to Nadila and enveloping her. I was filming on my phone, wishing I could just absorb the moment instead.

It had been 1338 days since Sadam and Nadila had last seen each other on 12 April 2017. Their unbroken faith had been rewarded, but the epicentre of the whole storytheir reason to keep goingwas clearly feeling less sure about all this.

Lutfi knew who his father was, of course, having seen him almost every day of his life on a phone screen. Still, for a three-year-old who has only known the physical reality of one parent to be suddenly confronted by this man wrapping his arms around his mother, giving physical vent to the stress he had been under for so longwell, it was a bit much. Lutfi took one look at the toy that Sadam, down on his haunches with an expression of hopeful terror, was offering him and took off.

He didnt go far, just behind the nearest pillar a few metres away from his parents. He looked across at them, suspicion mingling with curiosity and what I recognised later as an innate sense of self-possession.

That moment sits in my memory, a perfect representation of what the family had been through to arrive here, and what I had been so privileged to observe. A young couple sustained through their separation by love, finally together but both looking anxiously at the child for whom their sacrifices had been made, their lives suspended. And the child, looking back at the sudden strangeness of having two parents, unsure.

The day before I left China, my dad took me aside and said, Dont come back. When you get to Australia, stay there.

Within a few months of my departure, that decision would become an easy one to make. But I hadnt needed to be told anyway; for as long as I could remember, Id never wanted to be in China.

My dad is a Uyghur (pronounced wee-gur), from the town of Ghulja, high up in the mountainous north-western part of Xinjiang (shin-je-ang) near the border with Kazakhstan. Its one of the remotest areas in China. His dad had come from an even further-flung place, called Atush in the Kyrgyz autonomous prefecture on the very western edge of China. My grandfather, I was told, had been a rich merchant, but something had gone wrong and he was forced to move to Ghulja, losing all his money and even spending some time in prison.

Next page