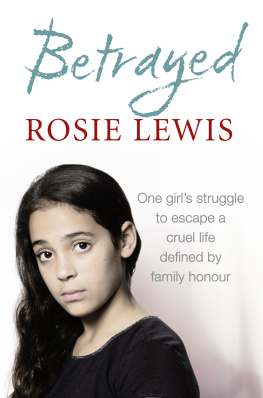

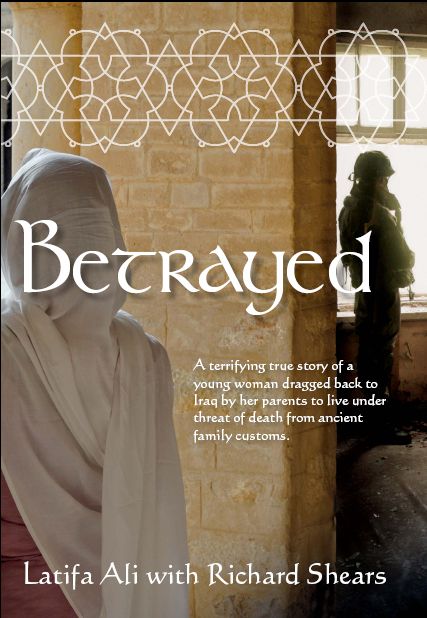

B ETRAYED

First published in Australia in 2009 by

New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd

Sydney Auckland London Cape Town

www.newholland.com.au

1/66 Gibbes Street, Chatswood NSW 2067 Australia

218 Lake Road Northcote Auckland 0746 New Zealand

86 Edgware Road London W2 2EA United Kingdom

80 McKenzie Street Cape Town 8001 South Africa

Copyright 2009 New Holland Publishers:

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing in Publication data:

ISBN 9781741108118

e-ISBN 9781921655081

Betrayed

E SCAPE FROM I RAQ

L ATIFA A LI WITH R ICHARD S HEARS

PROLOGUE

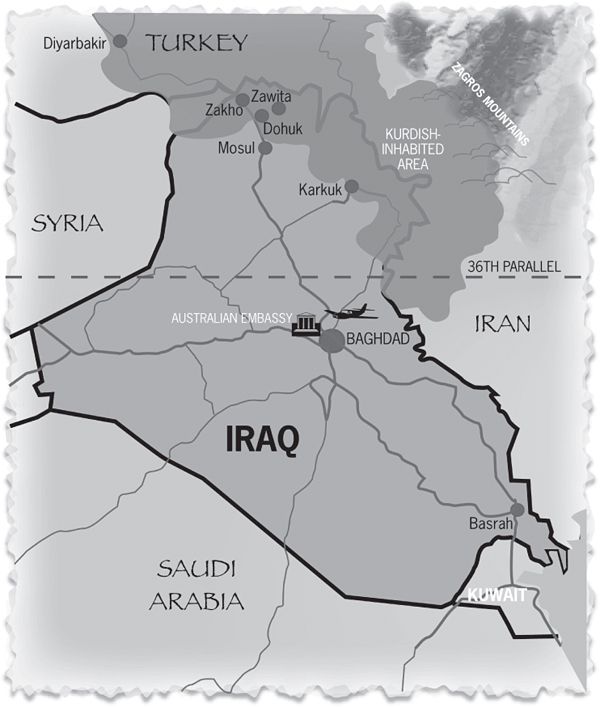

B y now the first of the snows were beginning to fall across the Zagros Mountains and the track was treacheroussteep ravines fell away to the fast-flowing Great Zab River, feeding the plains of Kurdistan below. Soon the paths through the mountain range would be impassable and with the temperature plunging to minus 10C the freedom fighters would return to their towns and villages, knowing that the Iraqi troopsand the Iranians who were always trying to penetrate the borderwould be doing the same. But that would be several weeks away and none of the freedom fighters, the Peshmerga, were ready to leave just yet.

A blanket wrapped around his traditional dark-khaki uniform, the guerrilla continued his climb to where he knew Khalid had positioned himself. Then he broke away from the path and began scaling the steep sides. Khalid would already have seen him from his snipers position but he felt quite safe, for no Arab soldier would travel alone through this territory unless he was pretending to be a Kurdish fighter and that would be a suicidal mission.

Khalid, he called against the icy wind, Khalid, Ive brought the news youve been waiting for.

The sniper burst up from his rocky cover. His checkered scarf hid his grin as he lifted his head high into the falling snowflakes and cried: Allah be praised!

Then he turned to the messenger. A boy? A girl?

I dont know, Khalid. This is the only word theyve sent. Theres a car waiting to take you back.

Khalid was 28 years old and very fit. He did not waste a moment. With his Kalashnikov thumping against his back on its strap he slithered down the hill, hit the path and ran on down towards the plains. Several times he slipped and came close to falling into the ravine, but his excitement overrode the danger. Then he tripped again, rolled and when he picked himself up he discovered he had lost his shoes. He looked around for them but realised they must have gone over the edge.

Now it was his bare feet which carried him over the stones. Tiny smears of his blood stained the light covering of snow, but he did not care about the pain. He wanted to reach his baby.

The 100 kilometre car journey seemed endless. He urged the driver ongo faster, faster!through the villages and then the streets of Mosul before at last they reached his home.

His 16-year-old wife, Baian, with the baby in her arms, smiled as he burst into the bedroom, where other female members of the family were gathered.

She held the baby up. Here is your daughter, she said.

Ah, so I have a girl, said Khalid. He didnt care that his first born was not a boy. There would be plenty of time for that.

Your feet, whispered one of the women. You are bleeding. Where are your shoes?

Somewhere up on the mountain, he said dismissively. It doesnt matter.

But it did. The loss of his shoes was to shape the destiny of the tiny baby girl he held so proudly in his arms on that cold November day in 1980.

ONE

I m known as Latifathe gentle onenow, although thats not the name my parents gave me. But dangers that came to surround me forced me to take on a new identity. Fear, threats and sufferingthey are nothing new to me or my people, the Kurds, who for centuries have struggled to keep out invaders and have their independence recognised.

In the decades before I came into the worldand before Saddam Hussein began his own brutal oppression in the 1980sthe Kurdish people, who make up about 20 per cent of Iraqs 20 million population, had suffered persecution under Iraqs former leader, President Ahmad Hasan al-Bakr. By the time Saddam Hussein placed al-Bakr under house arrest and declared himself president in 1979, my father was a fierce and respected member of that honoured group of Kurdish freedom fighters, the Peshmerga.

And how he was needed. There had been fierce clashes between the Iraqi army and the guerrillas in 1977, but in the following two years hundreds of Kurdish villages were razed to the ground and more than 200,000 Kurds were deported to other parts of the country. I never found out how many soldiers my father killed up there in the mountainsIve seen him shoot and I know how good he isand I know he would have been a one-man force to be reckoned with.

But now he was even more of a man among his peers. He was a father. And his bride, his wife, my mother, was among the most beautiful women in Iraq; blonde, green eyed and shapely, men would have killed for her hand but my fathers family claimed her for him when she was just 15.

Baian was born in Dohuk, the name of which means small village, but with a population today of half a million it is anything but small. With the mountains and the Tigris River nearby, it is an attractive city and its university is recognised as one of the best in the region. But my mothers loveliness denied her any university educationin fact, her family were so concerned that she might be molested or raped by government agents who search towns and villages for attractive girls and womenthat was the lifethat they even kept her home from school. She became a prisoner of her beauty.

It was her father who gave Baian her education because he was a teacher and she had the added advantage of learning from her three brothers and four sisters when they came home from school. But while her early teenage years put her ahead of her peers as a scholar, she was never allowed to mix with girls of her own age.

My mothers and my fathers families were distantly related through my great-great-grandmother, which was agreeable to everyone for it meant that when Baian and Khalid married the good genes were passed on. The wedding, like all Kurdish ceremonies, was a grand affair, with singing and dancing and much merriment and then the couple retired to their room. This was where the bride would give herself to her husband and heaven forbid any woman who was found not to be a virgin. Just as in other households, his mother and his oldest brother waited outside Baian and Khalids bedroom door for the moment when Khalid emerged. Then they went in and, taking no notice of the bride, inspected the bed. They were looking for the blood on the cloth. Yes, she was a true virgin and Khalid, well, he was now a man among men. Music was played, baklava was served. There was great rejoicing.

My father was to tell me years later, when I was old enough to understand, that he came to truly love my mother, although to this day I believe this is all the wrong way around and that love must come first. However, this was the Kurdish region of northern Iraq and that was the way things were.