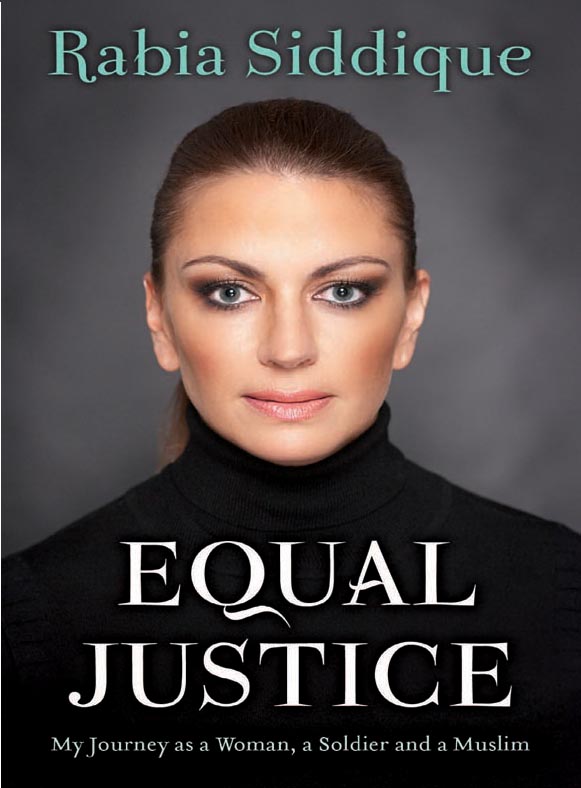

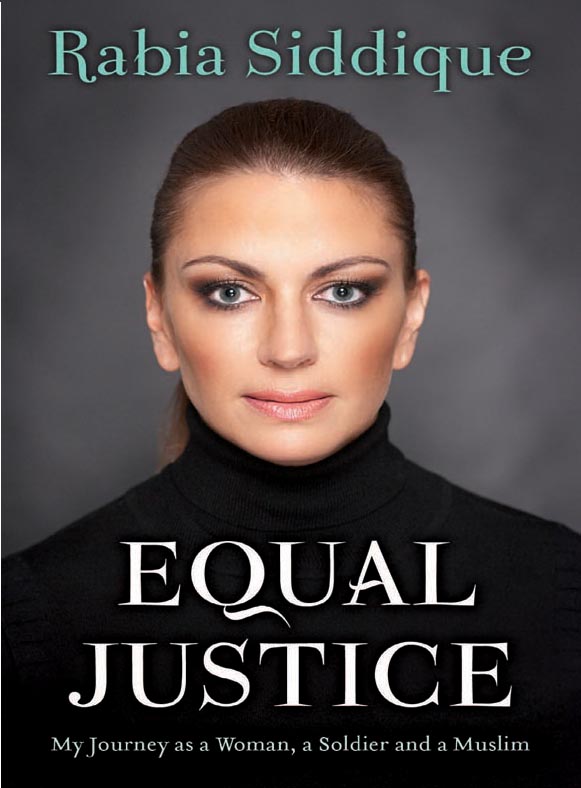

ABOUT EQUAL JUSTICE

Muslim, lawyer, soldier, hostage.

As the daughter of an Indian Muslim father and a white Australian mother, growing up in the conservative environment of 1970s Perth, Rabia Siddique was always going to be marked as different. Escaping her traumatic childhood, Rabia moved to London after graduating from law school to pursue her passionate commitment to social justice. She joined the British Army as a military lawyer just days after 9/11, finally finding herself stationed in Southern Iraq, where she pushed herself to make a difference in one of the most dangerous and testing environments on earth.

On 19 September 2005, Rabia and another soldier were taken hostage by Islamic insurgents as they tried to negotiate the release of two kidnapped British SAS operatives. She battled for hours to save their lives, using her legal expertise, knowledge of Islam and Arabic to negotiate with their captors as a violent mob tried to storm the compound where she was being held. After their release, her colleague received a Military Cross, while Rabia received nothing. Her subsequent sex and race discrimination case against the British Army made headlines around the world. Her memoir is a story of grit, courage and conviction, born out of a unique perspective.

This book is dedicated to the four gorgeous men in my life: Anthony, Noah, Oscar and Aaron, and is written in loving memory of my friends Charles Nathan Arnie Arnison and Assaf Al Nahi.

PROLOGUE

AL-JAMIAT

19 September 2005

I m sitting inside a British Army Lynx helicopter as it begins circling the sprawling Hayaniyah district in the port city of Basra, in southern Iraq. I dont want to be here but its my duty. Im a major in the British Army; Ive come to Basra to serve not just in the name of that army but also in the name of justice to protect the human rights of the Iraqis who inhabit this land we have made our home, no matter how temporarily and Ive just been given an order to get in this helicopter bound for al-Jamiat, the notorious police station in this desperate city.

As the chopper swirls around, a frightening, chaotic scene is unfolding below us: hundreds of furious Iraqis are trying to storm the compound around al-Jamiat. The only thing blocking their path is a cordon of British soldiers at the entrance. For these soldiers, the danger is obvious: many of the Iraqis have begun hurling petrol bombs, and black smoke is filling the sky above the compound. The violence is doubly alarming as theres a real possibility that Shiite militants in the crowd may begin firing rocket-propelled grenades at the foreign troops they so hate.

All this is taking place as the chopper brings us down, its blades cutting ribbons through the smoke. Im afraid of what awaits us here, among these men who want us gone so badly but Im also here to do my job. Theres no room for fear, not even for doubt. For now, the mission is what matters.

Im in Basra as the sole legal adviser to the UK brigade commander in Iraq, but whats put me in this helicopter is that it has fallen to me a 33-year-old, Australian-born military lawyer from a Muslim background to help save the lives of two British Special Forces soldiers who are being illegally held captive somewhere inside the police station compound.

So here I am, wearing full-body armour and cradling an SA80 assault rifle between my knees. I have a moment to wonder whether many other military lawyers have found themselves so far out of their comfort zone, rescuing SAS soldiers from Islamic extremists. It certainly wasnt part of my job description when I joined the army as a lawyer, looking for something different from the routine of law firms, client meetings and court visits. I joined because being a lawyer in the army afforded me the opportunity to practise law in a way that had meaning for me. In Basra, that has meant acting on behalf of Iraqi citizens. Right now, it means heading into a situation with a completely unpredictable outcome.

The Jamiat police station is an extremely dangerous place for any member of the British Army, let alone our two SAS soldiers. Its the headquarters of the Serious Crimes Unit (SCU), which local Iraqis refer to without joking as the Murder Squad.

They know, and we know, that the SCU is staffed and run by members of a Shiite insurgency group called Jaish al-Mahdi, which was set up a couple of years ago by the notorious anti-occupation cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. The SCU really are the bad guys. By day, they masquerade as police officers; by night, they kidnap, torture and murder Sunnis, foreign civilians and soldiers, as well as liberal members of the Iraqi community who refuse to be told what to do by the Islamic fundamentalists trying to invade all forms of government in southern Iraq. The British have controlled southern Iraq and Basra since the 2003 invasion, when Saddam Hussein was overthrown, but the infiltration of the citys police force by Jaish al-Mahdi insurgents has put everyones lives at risk.

The police officer who essentially runs the SCU is a man called Captain Jaffar. We have good intelligence that Jaffar is a senior member of Jaish al-Mahdi and, accordingly, his house has become the focus of a covert surveillance operation. The two SAS soldiers were involved in this operation when they aroused the suspicions of local Iraqis, who noticed the two strangers dressed in civilian clothing and wearing shemaghs, or Arab scarves, around their faces driving around in a car and taking photographs. The locals alerted the police, who set up a checkpoint to intercept the pair, but when the soldiers spotted the checkpoint they opened fire, reportedly seriously injuring one of the policemen.

The soldiers took off as fast as they could, but didnt get far before their car was surrounded by Iraqi police, who forced them to a halt. The soldiers, whom Id met and knew by their pseudonyms as Ed and Di, immediately identified themselves as members of the British military. At this point they should have been handed over to the British military occupation authorities, as required under the Status of Forces Agreement between the British and Iraqi governments. Instead, the police clubbed them with rifle butts and took them directly to the Jamiat apparently on Jaffars orders, after his men had contacted him and alerted him to the incident.

When we heard what had happened, back at our base at Basra Airport, we feared the worst. Only two days earlier, British and Iraqi troops had arrested and detained a man called Ahmed al-Fartusi, who we knew was the head of the southern Iraq arm of Jaish al-Mahdi. If the condition for letting Ed and Di go was Fartusis release as we suspected it might be then we were all in very big trouble.

So the news was grim even before an update came through a short time later, about rumours being spread throughout the city: that the strangers arrested by the police were, in fact, Israeli spies. This is just about the worst thing that anyone could allege about our two soldiers. Iraq and Israel are not friends and never have been. Just as they were meant to, the rumours sparked huge anger and brought hundreds of enraged Iraqis to the entrance of the police station, where they are now watching our arrival.

As soon as we learnt the soldiers were in the Jamiat, the head of the UK brigades surveillance unit, Major James Woodham, was sent to try to persuade the police to release them. By the time he was allowed to see them, they were bloodied, blindfolded and chained to chairs in a cell. But his negotiations to have the pair freed went nowhere.

Next page