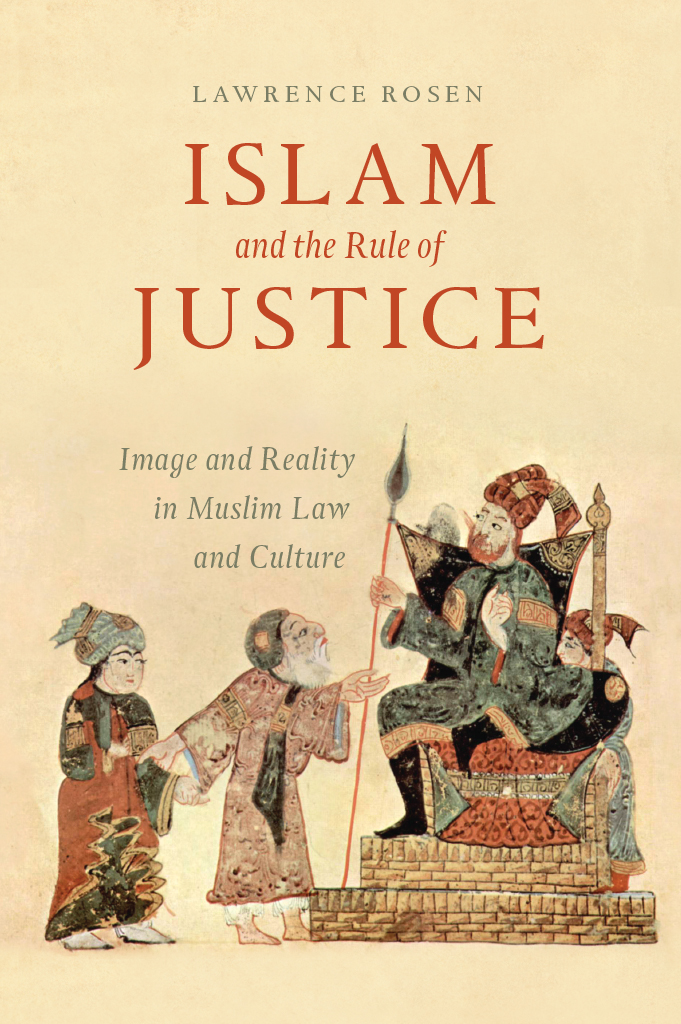

Islam and the Rule of Justice

Islam and the Rule of Justice

Image and Reality in Muslim Law and Culture

LAWRENCE ROSEN

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-51157-3 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-51160-3 (paper)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-51174-0 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226511740.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rosen, Lawrence, 1941 author.

Title: Islam and the rule of justice : image and reality in Muslim law and culture / Lawrence Rosen.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017037408 | ISBN 9780226511573 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226511603 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226511740 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Islamic lawInterpretation and construction. | Islam and justice. | Islamic lawSocial aspects. | LawSocial aspectsMiddle East.

Classification: LCC KBP 440.32 . R 67 2018 | DDC 340.5/901dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017037408

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

FOR MARY AND TITA

Contents

FIGURES

Anti-sharia protest sign, Idaho |

Israeli-Palestine separation wall graffiti by Banksy |

Payment of a bribe |

Woman in the Blue Bra and related graffiti, Tahrir Square, Cairo, December 2011 |

Sign held by young man in Tahrir Square: Leave [Mubarak]I Want to Get Married |

Older men in Tahrir Square |

Bouazizi visited in hospital by President Ben Ali (Tunisian government handout) |

Ordinary citizens sweeping Tahrir Square |

Zacarias Moussaouis mother, Aicha el-Wafi, with a picture of her imprisoned son, December 12, 2001 |

Moussaoui before Judge Brinkema |

Moussaoui, graduating with a British business degree, under arrest, and as a young man |

Portions of this book were written while I was a fellow of the Stanford University Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, and I am most grateful to its director, Iris Litt, and staff. Particular chapters in this book have profited from the helpful suggestions of scholars in the field and I am pleased to be able to thank them in the notes, without, of course, holding them in any way responsible for the final product. Lectures based on various chapters have also benefited from comments by participants at Cardozo Law School, University of California at Los Angeles, University of Victoria, University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, the U.S. Naval Academy, and the Central Illinois Mosque and Islamic Center of Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. To all I am most indebted. Edmund Burke, III, and Abdellah Hammoudi, as always, have listened critically to my arguments and are as blameless for the results as they are blameworthy for stimulating my thinking.

Parts of several chapters appeared in earlier forms and are reprinted here by agreement: Studying the Muslim Courts of Morocco, in Islam in Practice, ed. Gabriele Marranci (London: Routledge, 2014): 2133; Understanding Corruption, American Interest 5, no. 4 (March/April 2010): 7882; A Guide to the Arab Street, Anthropology Now 3, no. 2 (September 2011): 4147; Will the Middle Class Save the Middle East?, Contemporary Islam 5, no. 2 (2011): 18590; Power vs. the People, a review of Elizabeth F. Thompson, Justice Interrupted: The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East, Literary Review (London), October 2013, pp. 2324.

This book is dedicated to Mary Schmidt and Teresita Tiansay Voelkner, dearest of friends.

Approaching Islamic Law

Some years ago I co-chaired a meeting of French and American scholars of North Africa. To stimulate discussion I suggested that at our first, informal session we share stereotypes about one anothers different approaches to the region. The advantage, I suggested, was that we would all know that they are just stereotypesbut (I quietly assumed) we would all, to some extent, really believe that they are true. Through stereotypes we could, however, express ourselves unreservedly and then hide behind the excuse that what we were saying was, we knew, just an exaggerated likeness.

The exercise worked wonderfully well: the French told us that Americans come into the area for a few years and then rush off to the next part of the world, while they devoted their entire careers to one place; and my American colleagues told the French that they were too wrapped up in structural schemes to see the ambiguities in which we colonials delight. No one took offense, we all felt better afterward, and we all appreciated that although stereotypes can be unfair, and even if they contain a grain of truth, they may do far more harm than good.

It is somewhat in this spirit that I begin by addressing a set of misperceptions of Islamic law. Although the central focus of this book is to analyze rather than debunk, it is desirable, at a time when the actions of the Taliban and ISIS would seem to validate Western fears and misunderstanding, to address some of the oversimplified views commonly held about Islamic law. A few precautionary notes are, however, worth highlighting.

The predominant focus of this book is on the Arab world, even though it represents only a fraction of the worlds Muslim population. Moreover, when I speak of the Arabs it is necessarily in rather general terms, the phrase having to encompass a very wide range of local and historical instances. But if one approaches this diversity in the sense of embracing a range of variations on shared themes, rather than as seeking some definitive essence, readers may wish to ask themselves two interrelated questions: In what sense does what is being described correspond to what has been learned about other parts of the Muslim world, such that one is stimulated to think more carefully about each of those situations? And in what ways do these variations affect one another and the non-Muslim world, since none of the countries or situations described exists in isolation? Taken in this spirit the specific situations to be presented here may help in formulating more precise questions raised by the practice of Islamic law.

FIGURE 1.1. Anti-sharia protest sign, Idaho (conservativeinfidel.com).

That stereotypes of Islam, the Middle East, and Muslim lawfavorable and unfavorableare widespread is evident from even the most causal reading of the Western press. When the Archbishop of Canterbury (2008) suggested that Islamic law forums might be appropriate for handling certain family law matters of Muslims living in the United Kingdom he was roundly excoriated by those who acted as if he had proposed stoning adulterers or hacking off the hands of thieves, notwithstanding the frequent recourse to similar religious courts by Britons of other faiths. In March 2014, the Law Society of Great Britain offered instructions for drawing up a will in conformity with Muslim inheritance practices that grant one-half portions to women as opposed to men and no inheritance to children born out of wedlock, but the outcry was so great that eight months later In short, one only has to keep up with the nightly news and op-ed commentary to witness images of Islamic law as brutality against women and punishments of Biblical intensity in order to realize how deeply these stereotypes influence the popular imagination.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).