THE JUDGMENT OF CULTURE

Legal systems do not operate in isolation but in complex cultural contexts.

This original and thought-provoking volume considers how cultural assumptions are built into American legal decision-making, drawing on a series of case studies to demonstrate the range of ways courts express their understanding of human nature, social relationships, and the sense of orderliness that cultural schemes purport to offer. Unpacking issues such as native heritage, male circumcision, and natural law, Rosen provides fresh insight into socio-legal studies, drawing on his extensive experience as both an anthropologist and a law professional to provide a unique perspective on the important issue of law and cultural practice.

The Judgment of Culture will make informative reading for students and scholars of anthropology, law, and related subjects across the social sciences.

Lawrence Rosen is the William N. Cromwell Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Princeton University, USA, and Adjunct Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, USA. As an anthropologist he has worked on Arab social life and Islamic law; as a legal scholar he has worked on the rights of indigenous peoples and American socio-legal issues. He is a member of the bar of the State of North Carolina and the U.S. Supreme Court.

THE JUDGMENT OF CULTURE

Cultural Assumptions in American Law

Lawrence Rosen

First published 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2018 Lawrence Rosen

The right of Lawrence Rosen to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record has been requested for this book

ISBN: 978-1-138-23778-0 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-23779-7 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-29899-3 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo

by codeMantra

For

Terry MacTaggart and Carol Zanca

colleagues and friends

Many of the issues considered in this book have a long history of thinking and re-thinking, and were I to acknowledge all those who have shared in their development the list would be inordinately long. For support, however, I wish to thank the School for Advanced Research, Santa Fe for the William Y. and Nettie K. Adams Fellowship in the History of Anthropology, the Stanford University Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences for appointing me as a Mellon Fellow, the University of Arizona School of Anthropology for hosting me as a Residential Scholar during their centennial year, and my colleagues and students at Princeton University and Columbia Law School. I have also benefited from the comments by attendees at my University of Oxford Socio-Legal Studies Annual Lecture and as a Phi Beta Kappa Lecturer, as well as at talks I have presented at the University of Geneva and the law schools at the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Michigan, New York University, and Duke University. A special note of thanks is due to Therse de Vet and J. Stephen Lansing for the gracious loan of their Tucson home where portions of this book were written and to Matt Birkhold for many insights he added to the various topics raised here. Jeremiah D. LaMontagne was enormously helpful with the illustrations. The Native American Rights Fund allowed me to spend a summer as a legal intern when I was in law school, a privilege whose intellectual rewards I have gratefully reaped over the course of many years.

Sections of some of the chapters in this volume appeared previously and are reprinted by agreement with the original publishers: Metaphor and the Narration of Native Intellectual Production, Michael Hanne and Robert Weisberg, eds., Metaphor and Narrative in the Law, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017; Natural Law, Religion, and the Jurisprudence of the US Supreme Court, in Franz von Benda-Beckman, et al., eds., Religion in Disputes, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 183200; Anthropological Perspectives on the Abolition of Marriage, in Anita Bernstein, ed., Marriage Proposals: Questioning a Legal Status, New York: New York University Press, 2006, pp. 14770; and The Anthropologist as Expert Witness, American Anthropologist, vol. 79, no. 3 (September 1977), pp. 55578.

The book is dedicated to my friends and colleagues Terry MacTaggart and Carol Zanca who have had to put up with my ramblings, on land and at sea, only to be punished for their forbearance and good humor with yet more musings by a grateful author.

Left at large as we are.

[To Judge Learned Hand from Justice Felix Frankfurter. December 6, 1947. Supreme Court of the United States:] Dear B, I await with an eagerness bordering on impatience the full text of your opinion in the Repouille case. Apart from all the questions that arise in connection with mercy killing, my interest is aroused by the psychological-judicial problem that confronted you, namely to what extent may a judge assume that his own notions of right moral standards are those of the community? But if it is his jobas you and I believe it to beto divine what may rightly be deemed the standards of the community, by what process is he to make that divination? How and whether should he look for disclosures of the communitys mores?1

* * *

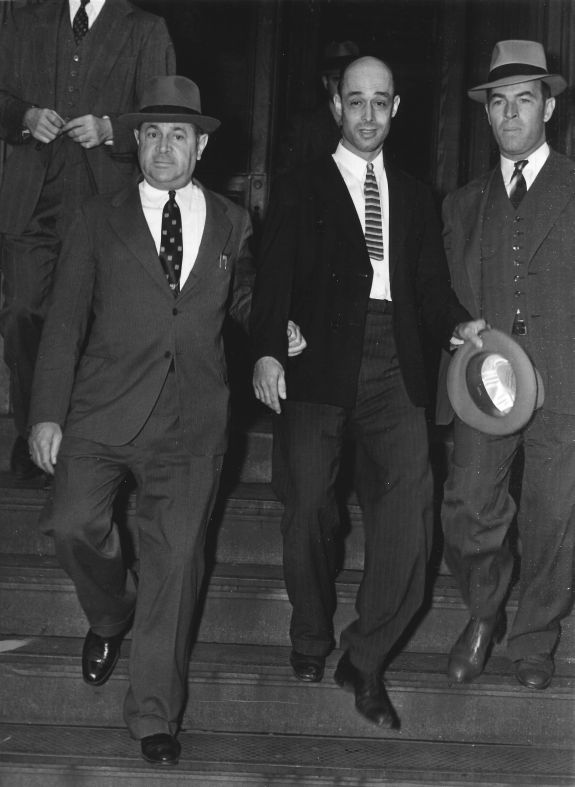

In 1947, a case came before the Federal Court of Appeals for the First Circuit in Boston. Sitting on the three-judge panel were two cousins with the stentorian names of Learned and Augustus Hand; the third judge was Jerome Frank, a no less redoubtable and articulate figure.)

Source: Acme Newspictures, October 12, 1939; photo owned by author.

Writing for the two-man majority, Learned Hand appeared stymied. In his youth a very religious man who later became an agnostic, Handwho was at once a politically active Progressive, a strong proponent of judicial restraint, and often described as the most influential judge who never sat on the Supreme Courtexpressed his uncertainty, if not indeed his anguish, in the following terms ():

[O]ften questions will arise to which the answer is not ascertainable.Indeed, in the case at bar itself the answer is not wholly certain; for we all know that there are great numbers of people of the most unimpeachable virtue, who think it morally justifiable to put an end to a life so inexorably destined to be a brutish existence, lower indeed than all but the lowest forms of sentient life.Left at large as we are, without means of verifying our conclusion, and without authority to substitute our individual beliefs, the outcome must needs be tentative; and not much is gained by discussion. We can say no more than that, quite independently of what may be the current moral feeling as to legally administered euthanasia, we feel reasonably secure in holding that only a minority of virtuous persons would deem the practice morally justifiable, while it remains in private hands, even when the provocation is as overwhelming as it was in this instance.3