Contents

Guide

Page List

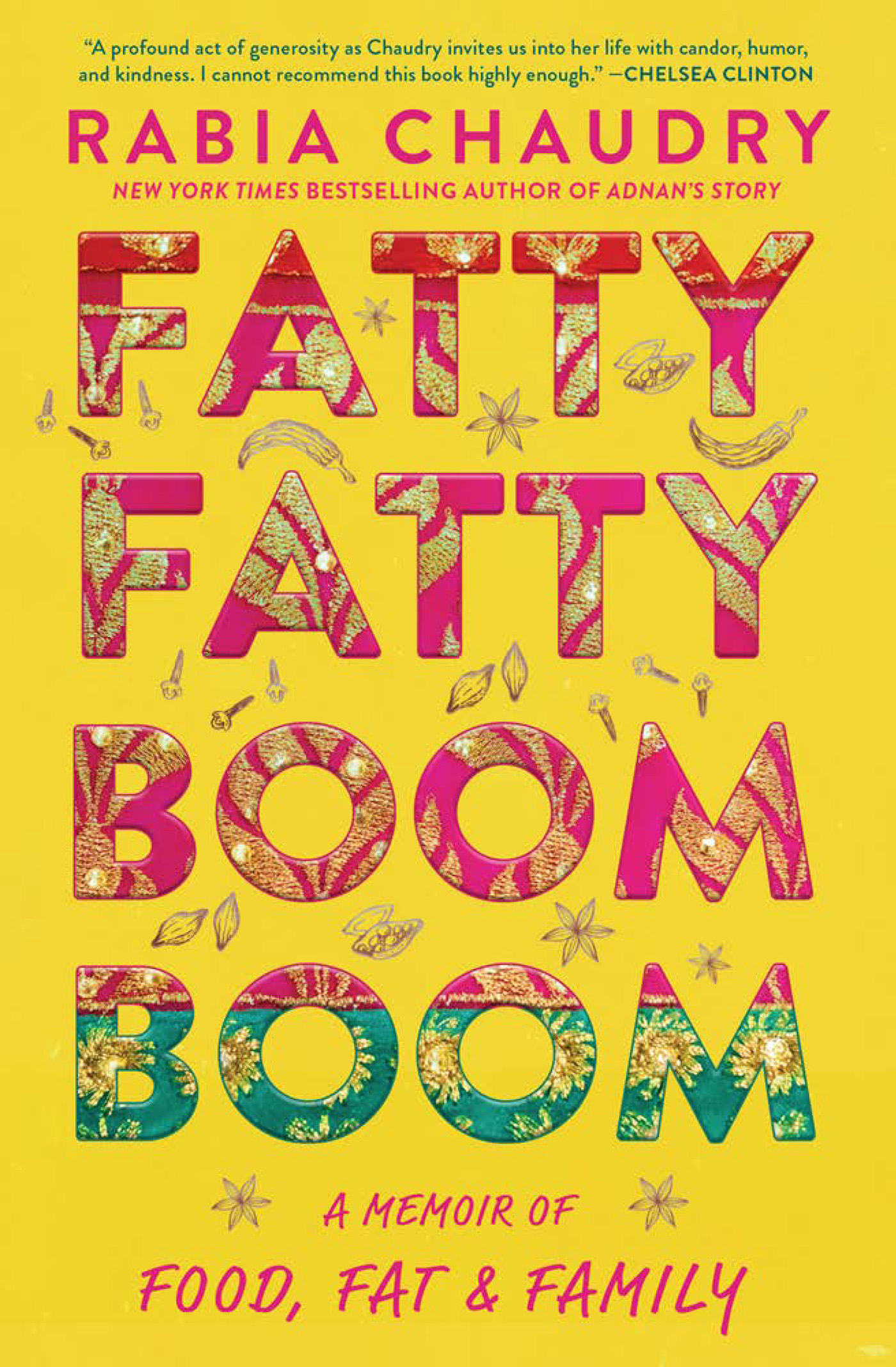

Fatty

Fatty

Boom

Boom

A Memoir of Food, Fat, and Family

Rabia Chaudry

This book is dedicated to all the mothers who taught me their

ways in the kitchen: Ami, Zuby Aunty, Nani Amma, Lilly, and my

mothers-in-law, both current and, yes, even the ex.

It is also dedicated to Abu, my rock through literally thick and thin,

and to Irfan, my partner in fatty and fitness pursuits for

the past sixteen years.

Finally, it is dedicated to all those who have spent their lives being

judgedand judging themselvesfor their weight, who have struggled

between deprivation and depravity, and who deserve like anyone else to

live an abundant life full of great food.

Damned if you do, damned if you dont.

Contents

One

Doodh, Dhai, Makhan: Milk, Yogurt, Butter

She swears the first time she saw him was on their wedding night. Her family had tried to show her his picture, but she turned away from it, resigned to her inescapable future. What was the point when she had no choice but to marry him?

Thats how the legend goes, legend precisely because while everyone who knows my mother has heard the story hundreds of times, it could be completely made up. Shes like that, and if it makes for a good story, it gets repeated until its canon.

Back to the wedding though.

Khalida Khanum Ghauri, intimidating in name and presence, my Ami, was a singularly independent woman in 1970s Lahore, Pakistan. At the age of twenty-six, when the marriage proposal came to her, she was the headmistress of the Lahore Girls College, a position she had held for half a decade at that point. No one becomes a headmistress at the tender age of twenty, in charge of overseeing much more senior staff and faculty, unless theyre a force to be reckoned with.

Few were as formidable as Ami. She was tall and slender, but big-boned like her father and his sisters: broad shoulders, large hands and feet, a frame just begging to be filled out. Her jet-black hair hung straight down to her waist in a tightly knit braid. She had large almond eyes over a delicate, sharp nose, and perfect bow lips that were almost permanently pressed into a sober, and sobering, line.

She was not one for nonsense. All six of her younger siblings knew it, and so did her parents. She barely mixed with the family, claiming the sole bedroom on the second floor for herself. Every morning her birdlike mother delivered a tray of breakfast before the headmistress left for work in a horse-drawn tanga, a covered buggy reserved for her commute. Every morning she got an egg fried in pure ghee, a luxury no other sibling was afforded.

In the evening, when she returned home, she retired to her room, where a dinner tray was brought to herusually a choice piece of meat in a rich, brown broth, with rice saved from that nights supper and covered with a lace doily. Meat that, again, not everyone in the large family was given.

Still, she felt suffocated, not just by the six siblings who were constantly present, but by the countless other relatives who rotated through their home in a continuous stream, including distant relations who would camp out for months in the already cramped quarters.

Ami both valued her independence and had developed a distaste for the institution of marriage itself, seeing women she knewaunts, cousins, friends, and even her own motherlose their identity and freedom in a morass of in-laws and squealing babies.

And for that reason, Khalida had rejected every marriage proposal sent her way since she had come of marriageable age.

Her stubborn refusals filled her parents with trepidation, as they considered how to approach her with my fathers proposal.

But this time, things were different.

Nana Abu, my maternal grandfather, a towering, barrel-chested deputy superintendent of police, was sick. Years of indulging in syrupy sweets had done a number on him, but even raging diabetes wasnt enough to convince him to clean up his eating habits. He had lived pleasing his palate, and would die doing so, too.

Nana Abu had been recently released from the hospital and was convalescing at home, but the writing was on the wall. If his eldest daughter didnt accept this marriage proposal, he would likely die without seeing any of his children married.

He called Khalida to his bedside. She listened as he told her she couldnt say no to this proposal, not this time. At twenty-six, she was virtually a spinster. The proposals, which once came fast and frequent, had nearly sputtered out. She had run out of time because he had run out of time. There were pictures of the prospective groom, he said, if she wanted to see. She quietly walked away, but this time without refusing the proposal.

That was her grudging acquiescence.

There was little to celebrate as far as Ami was concerned. What she knew didnt fill her with any excitement or joy. Her groom-to-be was thirty-two years old, a widower, and he came from a large middle-class Punjabi family on the other side of town.

Punjabis, she sniffed. She couldnt believe she was going to be married into Punjabis.

Sure, she had been born and raised in Lahore, the heart of Punjab province, but that was only because in 1946 her family, like many other Muslims, had left Delhi after rumblings of the Partition of India were beginning to grow. They made it into what would become Pakistan right before Ami was born, in January 1947, eight months before the border was drawn.

By that point, the British imperial project in India had lasted nearly two hundred years, beginning with the British East India Company, a trading company, seizing massive parts of the subcontinent thanks to its own private army. The company competed with the Dutch and Portuguese to strip India of natural resources, harvesting and selling her spices, cotton, silk, tea, indigo dye, and other goods, and grew so prosperous they eventually controlled half of the entire worlds trade.

After a hundred years, and in the face of an uprising by Indian soldiers in that private army, control of the company was transferred to the Crown, thus beginning the era of the British Raj in the subcontinent. In 1876 Queen Victoria was declared the Empress of India, and a decade later the Indian National Congress emerged, in opposition to the colonial rulers.

The call for independence grew over the next six decades, and under the leadership of inspirational political leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, it eventually became reality. But another call ran parallel to the call for independence from Great Britain: a demand for partition and thus the creation of a sovereign nation for Muslims, who comprised 20 percent of the Indian population. In 1940 Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League party, delivered a resounding two-hour speech that came to be known as the Pakistan Resolution. It eventually became clear to the British that a transition to independence for India couldnt be achieved without the creation of Pakistan as well.

And so the last British viceroy of India, Lord Louis Mountbatten, a highly celebrated and decorated navy commander, was tasked with splitting the motherland in two and overseeing the transition to independence by June of 1948.

But he didnt want to take that long.