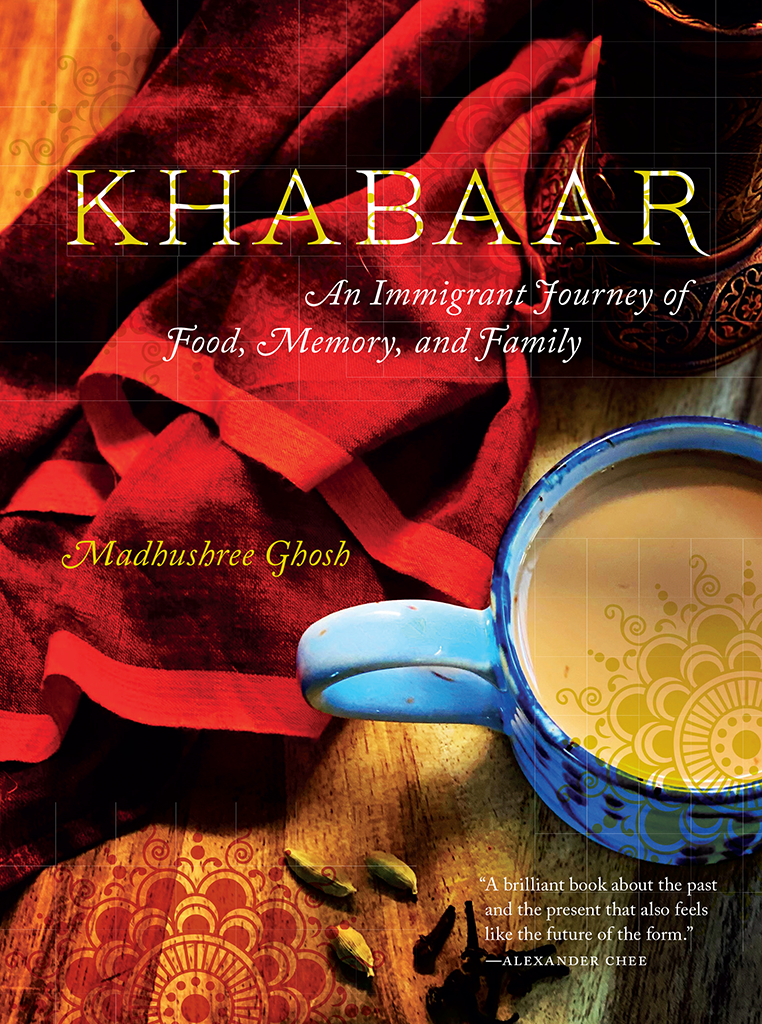

KHABAAR

FoodStory

Nina Mukerjee Furstenau, series editor

KHABAAR

An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory, and Family

Madhushree Ghosh

UNIVERSITY OF IOWA PRESS,

IOWA CITY

University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242

Copyright 2022 by University of Iowa Press

uipress.uiowa.edu

Printed in the United States of America

Design by April Leidig

No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach.

Printed on acid-free paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ghosh, Madhushree, author.

Title: Khabaar: An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory, and Family / Madhushree Ghosh.

Description: Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, [2022] | Series: FoodStory | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021045194 (print) | LCCN 2021045195 (ebook) | ISBN 9781609388232 (paperback; acid-free paper) | ISBN 9781609388249 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, Bengali. | Ghosh, MadhushreeFamily. | ScientistsUnited StatesBiography. | East Indian American womenBiography. | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX724.5.I4 G474 2022 (print) | LCC TX724.5.I4 (ebook) | DDC 641.595492dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021045194

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021045195

Another world is not only possible, shes on her way. Maybe many of us wont be here to greet her, but on a quiet day, if I listen very carefully, I can hear her breathing.Arundhati Roy, Come September,

My Seditious Heart, 2019

For Baba and Maei je, etaa nao

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

Khabaar tackles not only how immigrant food and South Asian food in particular traveled through colonization, migration, refugee journeys, and indenture; it is also about my childhood as the daughter of refugees and as an immigrant myself. While I pride myself in my memory, I am acutely aware that what I remember, or choose to remember, is what I want my world to adjust to. I have kept the names of most of the people in the essays as is and noted when I may be misremembering them. I have discussed with my surviving family members incidents that I am certain of, although they have sometimes remembered them very differently. I have stayed true to my recollection in Khabaar and am true to the memory fades, memory adjusts Didion school of thought.

I have also called the neighborhood I grew up in Chittaranjan Park or C. R. Parkboth have been used interchangeably. If you talk to anyone from there, whether they still live in that neighborhood or are elsewhere in the world, I can guarantee you they too will use both descriptors interchangeably.

The colonization of the mind and of our immigrant stories is a problematic minefield indeed. It takes decades for multilingual authors like myself to take a stance on how to present words that arent English but that I grew up with. Should we italicize words our mothers raised us with or not? Are these words foreign, and if so, to whom? If a reader doesnt understand the word, what will they do? Stop reading? Start exploring? After all, isnt that what we do ourselves as writers, readers, and learners? Why then, this italics-policing by many publishers to highlight an exotic, foreign, unfamiliar word? Read the sentence. Read the story. Youll get it. Or youll ask.

It is easy for me to devolve into irrational rage. Its natural to internalize racism, sexism, even hatred, and descend into victimhood. I wrote Khabaar to understand what we question and what we track and how we follow the journeys of immigrant food stories. Jumoke Verissimo italicizes her Yoruba words to assert her selfhood through her writing, primarily because she learned English as a result of colonial legacy and education.

There have been multiple nudges to italicize Bengali and Hindi words in Khabaar. As a scientist by training, an immigrant by choice, and the daughter of refugees by destiny, to call myself one or the other feels like othering myself. Italics add another dimension to this exclusion. I can be one and the other. I choose not to italicize Bengali, Hindi, or other Indian language words. I hope you use or start to use them as liberally as I do here and in life. I do italicize khabaar because I want you to pay attention, not because it is foreign or simply because its the book title.

In Bengali, we have twice as many vowels and consonants as the English alphabet. S is usually pronounced as sh and s has three distinct characters in the Bengali script. Ive tried to keep the Bangla transliterations to as close to how we would pronounce it in my familypeople who moved from Dhaka and Barisal to Kolkata, then New Delhi and now America through Partition and immigration.

This then brings us to the concept of food and its appropriation by white, English-speaking people. Imperialismand as a result colonialismhas the dubious distinction of evangelizing spices and cuisines of colonized lands. I dont think we need to debate that. While Old World colonizers, such as the British, Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese, currently have a significantly reduced influence, the New Order imperialists, such as the United States and China, that have colonized Africa, Latin America, and parts of South Asia, are flourishing.

What does it mean when our lands are colonized? The stories are well known, but the impact over generations is felt through many layers. How are my ancestors connected to a Singapore kopitiam stall selling prata or a Durban restaurant selling lamb bunny chow? That story may be lost or, as it often happens in our cultures, passed down through oral lore, changing and morphing over the years.

Appropriation, however, especially of cuisines, remains constant. It seems that were outraged daily about racist and toxic environments for BIPOC in food-focused companies, magazines, and media la Bon Apptit and New York Times columnists. Co-opting in a white-centric world reinforces a white norm, a whitewashing of a food that has existed independently for centuries. While the topics are intertwined, to ignore privilege in India while talking about khabaar would be doing immigrant journeys a disservice.

Privilege in India comes through not only through colonization and our calculated association with those colonizers but also through wealth, which in turn is a result of class and caste. If we as South Asians and/or South Asian Americans dont acknowledge our societal status, which enables us to explore food journeys so easily or learn how lack of resources devastates lower castes and the casteless, we cant address what these food journeys truly inform.

Sharanya Deepak highlighted how food scarcity led Dalitsthe untouchables, casteless people in the Hindu caste systemto create innovative cuisine. When the untouchables are excluded from the Hindu caste system, denying them opportunities, foods, places of worship, and the right to equality, they improvise. Food tells the story of how middle-class families like mine separated the utensils used for the help from ours and ours from the guests who were given food on plates of the highest quality. I acknowledge my privilege. I learn to check it daily, and I work to unlearn every day.

I hope the journey youll embark on with this book will spark a discussion about immigrants like me, how we came to be, what was done to us, how we love, and what our food illuminates. But more important, I hope