Table of Contents

REMNANTS OF A

SEPARATION

A History of the Partition through

Material Memory

AANCHAL MALHOTRA

For her, who taught me the importance of ones soil

and

for him, who tried so hard to forget it

Contents

A LINE DRAWN ACROSS THE lives and homes of people is the initial moment in the formation of an archive one of the most evocative archives of the history of India. It is an archive of memory, of stories, of violence, of lost friendships and relatives. Lives lived and lost become the stuff of remembrance of things past. The Partition of India in August 1947 is one such moment of separation and uprooting when a new kind of archive began to be formed.

One part of the archive is well known and well mined the written documents that were prepared for the Partition that came with the birth of two independent nation states. The various narratives that have been constructed to understand how Partition and Independence happened together have used this documentary archive. But these documents, valuable though they are, do not begin to touch the lives of the millions of women and men who were directly affected when the motives of politicians dramatically altered their lives. People were forced to move, to flee, once India and Pakistan became two distinct political entities. This movement of population arguably one of the largest in the history of the twentieth century and packed, as it was, in a very short period of time was accompanied by a movement of memories and possessions, sometimes those about which the affected people were unable and unwilling to speak. Silence can also be the material for history writing, and so can objects, which by definition cannot speak.

Aanchal Malhotras book tries to address this question: what objects do people take with them when they are leaving/fleeing their homes with the full knowledge that they will never return? What do people carry with them when time as they know it has been forced to stand still and a new kind of time, a new and unknown rhythm of life, is poised to begin? It is difficult to conjecture. What is valuable? Do I take the most valuable or the most important? The answers, as this book shows, vary. Two other questions hover over the narratives that Aanchal constructs. One, what about those who did not even have the time to pick up an object when they fled to save themselves and their children and dear ones as madness and fury enveloped them? And two, in case of those who had the luxury of choosing, did they have regrets about choosing one thing over another? The objects that one did not take, the cupboard door one never opened these form the echoes in the memories of human beings who left behind, who lost, much more than they could ever carry. They carried memories sometimes too heavy to be borne.

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind cannot bear very much reality. It is this very much reality, as contained in objects, that Aanchal pursues.

This is an unusual book and I recommend it for its extraordinariness. It is a book about loss, about memories, but also about hope. Objects help to redeem time.

Prof. Rudrangshu Mukherjee

Chancellor, Ashoka University

August 2017

T HE PAST HAS BEEN surfacing frequently and unexpectedly these days.

It is March 2016. I return home from work to find my paternal grandmother, my dadi, hunched over the bed, sifting through a pile of metal. A plastic sheet has been spread over the mattress, and her elusive coin collection, unseen by me but talked about frequently by my father, has been toppled on to the sheet. For as long as I can remember, this coin collection has lived discreetly inside a blue velvet pouch. Rupee, paisa, anna, taka, dhela a veritable hoard amassed by her over the years. Mementos of monetary change in the subcontinent, some passed down from her mother and some her own. Today, they are strewn across the sheet, and my grandmothers long fingers pick at them erratically.

But this is not an unusual sight in our house, especially of late. My grandfather died a few weeks ago and the plastic sheet has been ceremoniously laid out many, many times since. As drawers and cupboards are gradually emptied, belongings are laid out some his, some theirs to be classified for keeping or discarding. Coupled with this sorting are memories, which inevitably tumble out alongside.

I stand at the door and watch her. Her eyebrows are knit together. Though Im not surprised to find her this way, I am curious since this is the first time Ive actually seen the collection.

What are you doing? I ask, visibly startling her.

I was sorting through some things and I found this pouch. It has my old coins. Purane zamane ke. She is speaking to me but her eyes have already returned to the pile. I come in and sit down on the cane chair next to her bed.

She is singling out the larger silver coins and laying them in a line, chronologically. From the front of the lineup, she picks one and holds it to the light. Then she wipes it clean and places it in the middle of my outstretched palm. It is heavier than I expect, minted in solid silver, dulling at the edges but still brilliant. ONE RUPEE INDIA 1920. The amount is written in English and Urdu and is surrounded by a floral wreath. I flip it over to find an image of the king, embossed in all his regal glory. George V King Emperor, it reads proudly.

Humne kya kya din nahi dekhe, she says distantly.

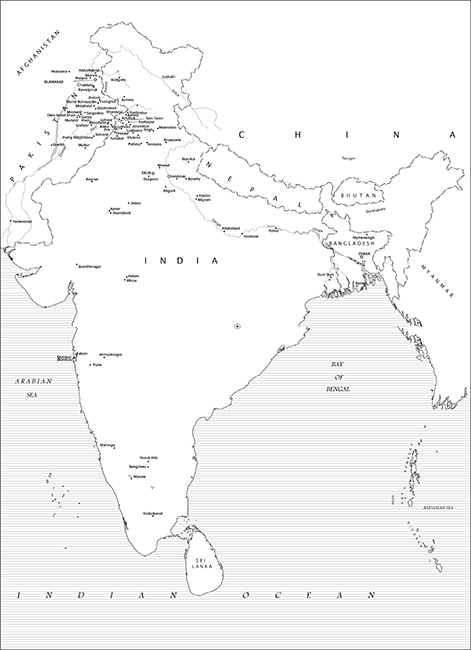

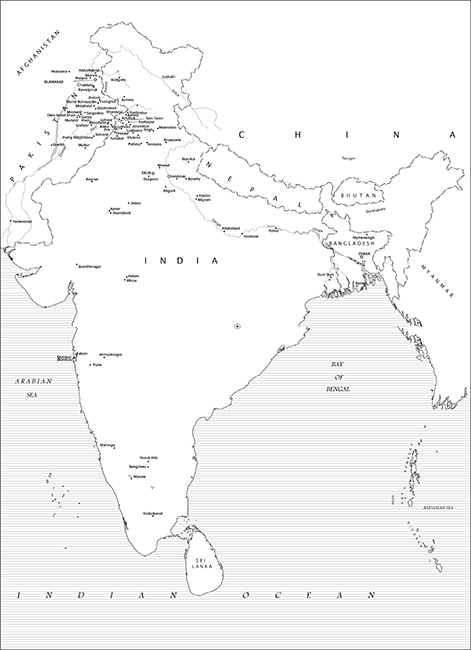

As I study the coin, I think about what she means when she says this. What have I not seen in my time. My grandmother was born in 1932 in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP, now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province) in Pakistan into an affluent family of landowners. Her father, the youngest of four brothers, passed away when she was a child, and her mother became a widow at the age of only twenty-five. They were cheated out of their share of the family property, leaving them in dire circumstances. In 1947, at the onset of the Partition, my great-grandmother and her five children fled across the border and arrived in Delhi.

In those days, one rupee was worth a lot of money. My grandmother is sitting next to me, yet her voice seems to be emanating from elsewhere. I remember this incident from when I was six or seven years old. We needed money for something important and my mother had none. It had to be something important or I wouldnt have done it, I wouldnt have asked. It was always me when money was involved. I was always the one sent out.

She pauses and runs her flattened palm over the sea of one-rupee coins.

I can still see the scene play out before me. The ancestral house was large and each of my fathers brothers had his separate quarter. I walked across the house to the room of my cousin my eldest uncles daughter-in-law who was much older than me. She had had nothing to do with the division of family property and seemed kind enough. So there I was, knocking on the door innocently, hoping that she would understand our plight. She opened the door and asked me what I wanted. Five rupees, I had said to her. Just five rupees, didi. We dont have anything, and this will last us the whole month.

Suddenly, she stops narrating and looks at me, her moist eyes boring into mine, and I realize that my grandmother has extracted perhaps the most heartbreaking memory from her past. Now, from the pile, she separates five of the one-rupee coins and stacks them on top of one another. Five rupees.