Introduction: City Beloved

Bapsi Sidhwa

I have spent most of my life in Lahore, and the city of eight million provides the geographical location of my novels. The citys ambience has moulded my sensibility and also my emotional responses. To belong to Lahore is to be steeped in its romance, to inhale with each breath an intensity of feeling that demands expression. This is amply illustrated by the bouquet of essays, verse, chronicles and memories that celebrate this anthology.

The very spelling of this hoary city causes one to indulge in linguistic anticsas I did in my first novel, A Pakistani Bride:

Lahorethe ancient whore, the handmaiden of dimly remembered Hindu kings, the courtesan of Moghul emperorsbedecked and bejeweled, savaged by marauding hordeshealed by the caressing hands of successive lovers. A little shoddy, as Qasim saw her; like an attractive but aging concubine, ready to bestow surprising delights on those who cared to court herproudly displaying Royal gifts.

According to popular myth, Lahore or Loh-awar (from the Sanskrit word awar or fort) was founded by Lav or Loh, one of the sons of the legendary Rama. But Lahore as we know it today owes its splendour to the Mughal emperors. Emperor Akbar moved his capital to Lahore in 1584 and built its massive fort; Emperor Jehangir and his son Shah Jehanthe indefatigable builder who commissioned the Taj Mahalextended it. Shah Jehan also commissioned the terraced Shalimar Gardens.

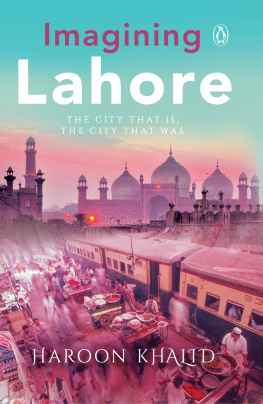

But it is the Badshahi Mosque, its massively billowing marble domes ignited by the setting sun as one approaches the city from the Ravi bridge, that conjures up the image of Lahore for me. Reputed to be the worlds largest mosque, it is laid out like a jewel before the main gate of Lahore Fort. Both structures originally stood on the banks of the Ravi, but the depleted river has meandered into a new course a couple of miles to the north. The Badshahi Mosque, its elegant proportions and the way it is situated in relation to the city, is sheer architectural poetry. For, above all, Lahore is a city of poets. Not just giants like Allama Iqbal or Faiz Ahmad Faiz, but a constellation of poets. Given half a chance, the average Lahori breaks into a couplet from an Urdu ghazal, or from Madho Lal Hussain or Bulleh Shahs mystical Punjabi verse, and readily confesses to writing poetry.

But if I toss up the word Lahore and close my eyes, the city conjures up gardens and fragrances. Not only the formal Mughal Gardens with their obedient rows of fountains and cypresses, or the acreage of the club-strewn Lawrence Gardens, but the gardens in thousands of Lahori homes with their riot of spring flowers. The trees bloom in a carnival of jewel-coloursthe defiant brilliance of kachnar, bougainvillea and gulmohur silhouetted against an azure sky. And the winter and spring air are headythey make the blood hum. On summer evenings the scent from the water sprinkled on parched earth signals respite from the furnace of the dayfor the summers are as hellish as the winters are divine.

There is a certain route I follow when I take visitors to my favourite Lahori landmarks. From my house in the cantonment near the old Lahore airport we drive to Mall Road. Believed to be part of the famed Grand Trunk Road that ran across the breadth of India from Peshawar to Calcutta, it has been grandly renamed Shahrah-e-Quaid-i-Azam, after the founding father of Pakistan. But old names, like old habits, die hard, and it is still commonly called Mall Road. Shaded by massive peepal and eucalyptus trees, its wide meridians ablaze with seasonal flowers, the avenue provides an impressive route for the dignitaries being wafted in their darkened limos to the Government House. Past the delicate pink sprawl of the British-built High Court and the coppery Zamzamah, the cannon better known as Kims Gun after Kiplings young hero, past the deadly little fighter jet displayed on the traffic island a little further along the road, our tiny Suzuki noses through the congestion of trucks, horse-drawn tongas, bullock carts and scooter-rickshaws to Data Sahibs shrine on Ravi Road.

One of the earliest Muslim saints to visit India, Data Gunj Baksh was embraced by all communities including the Hindus and Sikhs. I was regularly hauled to the shrine as a child. My mother had a committed and confidential relationship with the saint and was forever asking him to either grant her some favour, or thanking him for having granted it. On those visits, prompted by her gratitude, she would insert one or two crisp ten-rupee notes in the collection box just inside the grills of the tomb window. Sometimes, when the resolution of a particularly knotty problem merited extra thanks, she would also donate a deg or cauldron of sweet or savoury rice. The shrine provides food at all hours, and the path to the shrine is lined with merchants hawking enormous degs of steaming rice and lentils. Once the deg is paid for, two men haul it on bamboo struts to a comparatively vacant distribution lot a few yards away, and immediately a long line of labourers and beggars materializes before it as if beamed down from an airship. The labourers hold out the flaps of their shirts, and the women portions of their ragged dupattas, to receive the saucerfuls of rice ladled out by the hired help. It is alleged that the saint saved Lahore during the 65 and 71 wars with India. Sikh pilots are believed to have seen hands materialize out of the ether to catch the bombs and gentle them to the ground. How else can one explain the quantity of unexploded bombs found in the area? They cant all be blamed on poor manufacture, surely.

From Data Sahibs, I take my visitors to the monumental Lahore Fort. Running along one side of the old walled city, it is your standard Mughal bastion with thick, impenetrable stone walls, tall ramparts and neatly constructed turrets from which small cannons were fired long ago. One enters the fort through dwarfing gates that open on the wide canyon of the elephant walk. The walks gradual granite incline is marked by a series of small steps placed wide enough apart to accommodate an elephants stride. As an awed child, I once watched three richly caparisoned elephants conjure the spirit of bygone empires as, trunk to tail, they lumbered up the ancient path for some visiting dignitaries.

The walk leads to a spread of open courtyards and halls bordered by marble pillars and arching canopies, and finally we arrive at the million-mirrored Sheesh Mahal, the queens and princesses private chambers. If my preferred guide has not already attached himself to us, he can be counted on to do so now. Respectful and non-insistent, a rare quality in this indigent breed, he appears always to be loitering inside the fort. He leads us with a somewhat diffident air of mystery to the darkest portion of the Sheesh Mahal and, fetching a tiny box of matchsticks from the depths of his baggy shalwar, strikes a match. (The striking of a Lahori match is a chancy thing. It might ignite a sterile spark that produces no fire, or it might produce a weak fire that gutters out if not nursed.) Holding the anaemic fire like a fledgling in the cupped palms of his hands, the guide finally cajoles it into a robust flame and holds it aloft. For a few seconds all the little mirrors imbedded in the arches and vaulting ceilings of the chamber burst into flames and, as the guide slowly moves his arm about, the flames dance like a glittering chorus of Broadway fireflies.