Philip Mansel , who has lived and taught in Paris, is one ofBritains leading historians of France and the Ottoman Empire. Hisfirst book, Louis XVIII , together with subsequent works such as ParisBetween Empires, 18141852 , established him as an authority on thelater French monarchy. Mansels acclaimed Constantinople: Cityof the Worlds Desire was described by William Dalrymple asan impeccably researched masterpiece of exquisite historicalwriting. In 2012 he was made a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettresand received the London Library Life in Literature award. Hecurrently lives in London, and is editor of The Court Historian (www.courtstudies.org).

An eloquent and original study of the Bonaparte family, delightfully acute in its depiction of the vanities, rivalries and pretensions of Napoleon.

David Gilmour

author of The Pursuit of Italy

Clear, well-researched, always interesting.

Nigel Nicolson

History Today

Napoleon is presented in a new guise: the Eagle both in splendour and as chie-en-lit . The authors urbane and witty style [gives a] vivid description of the Napoleonic Court.

John Mackrell

Journal of Modern History

Mansels book derives from a sound archival and bibliographical base. It is hard not to agree with [his] perceptive comment that it has really been the manufactured splendour of style which accounts for the continuing fascination with the Emperor, of which this is a not unworthy example.

Clive H. Church

British Journal of Eighteenth-Century Studies

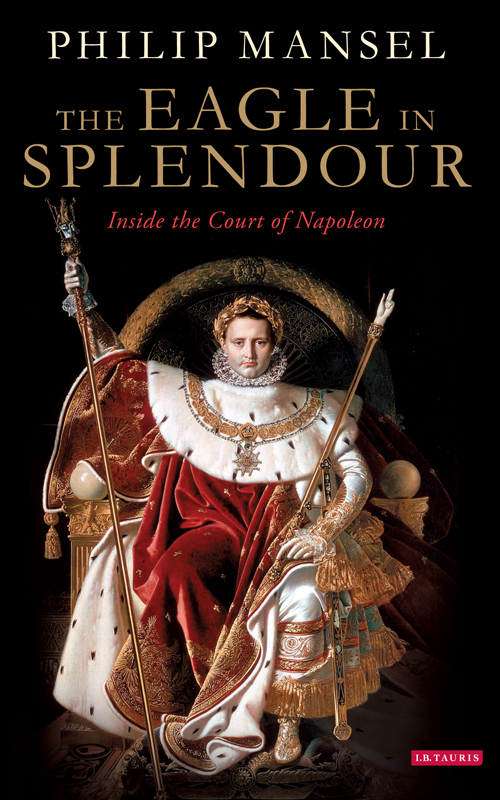

PHILIP MANSEL

THE EAGLE IN SPLENDOUR

Inside the Court of Napoleon

Neweditionpublishedin2015by

I.B.Tauris&CoLtd

London

NewYork

www.ibtauris.com

Firstpublishedinhardbackin1987byGeorgePhilip

Copyright1987, 2015PhilipMansel

TherightofPhilipManseltobeidentifiedastheauthorofthisworkhasbeenassertedbyhiminaccordancewiththeCopyright,DesignsandPatentsAct1988.

Allrightsreserved.Exceptforbriefquotationsinareview,thisbook,oranypartthereof,maynotbereproduced,storedinorintroducedintoaretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,electronic,mechanical,photocopying,recordingorotherwise,withoutthepriorwrittenpermissionofthepublisher.

ISBN: 9781784531751

eISBN: 9780857738950

AfullCIPrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

AfullCIPrecordisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

LibraryofCongressCatalogCardNumber:available

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

T he author wishes to thank all those who have helped withinformation or illustrations. In particular he would like tothank Princesse Minnie de Beauvau, G. Burlamacchi, RupertCavendish, Dr O. Clottu, Jacques Descheemacher, Ren andBatrice de Gaillande, Georges de Grandmaison, NicolaHoward, Grard Hubert, Comte F. de La Bouillerie, theMarquess of Lansdowne, Ulla Lind, Nicholas McClintock,Major and Mrs J. C. Mansel, Comte Louis-Amde deMoustier, Comte G. de Montesquiou, Jacques Perot,Jean-Michel Pianelli, the Countess of Rosebery, AdamZamoyski and Charles-Otto Zieseniss. He is especiallygrateful to David Higgs and Katherine MacDonogh forreading the manuscript.

Introduction

The Court Goes On

T he Eagle in Splendour was published in 1987, towards theend of the dark age of court history. Monarchies in general,and nineteenth-century monarchies in particular, were rarelystudied as systems of political, military and cultural power.Its purpose was to describe and analyse the court as apower-base; to stress the ultra-monarchical nature andextreme fragility of the First Empire; and to suggestthat the Revolution, far from diminishing the Frenchdesire for monarchy and court life, had sharpened it.It is re-issued in 2015, as court history is becoming amajor discipline. This Introduction adds new material,especially on the courts revival during and after the SecondEmpire.

Despite or because of his Jacobin past, GeneralBonaparte, First Consul of the French Republic, was anultra-monarchist. In 17991804, at the same time asintroducing a new constitution, with the Senate, Tribunateand Corps Lgislatif, he established a court system, in acalculated sequence of monarchising measures. First came aguard (1799); then official costumes (1800); residence andreceptions in the Tuileries palace (18001); a chapel headed byhis favourite composer Paisiello, whom he summoned fromNaples, since he preferred Italian to French music (1802); amonarchy, a dynasty and coronation (1804); finally anobility (1808). The choice of such a system, whenFrance was a victorious republic, and the rapidity withwhich Republicans adapted to it, proves its appeal. Thetransformation of France into a republic in 1792 had beenpartly due to contingencies: the executive gap left by theabsence of a vigorous monarch, minister or general; theradicalism of the National and Legislative Assemblies; andwar.

Pierre Branda has shown in a brilliant recent book on Napolon et ses hommes. La maison de lEmpereur,18041815 (2011), how Napoleon used his court asan instrument of domination and enrichment. Recenttheses have analysed particular departments of the court;Charles Eloi Vial has shown how the hunt was reformed,and the crown forests restocked with game, after thedevastations of the Revolution and the democratisation ofhunting rights. Rmy Hme de Lacotte has studied theGrande Aumonerie under the Empire and the Restoration,Olivier Varlan Caulaincourt, the Grand-Ecuyer whoaccompanied Napoleon back from Russia and was atrusted political adviser and minister as well as a courtofficial.

The imperial hunt shows the combination of rupture andcontinuity characteristic of nineteenth-century Frenchmonarchies. Napoleons Grand Veneur Marshal Berthier wasboth the Emperors chief-of-staff, and son of a royal officialat Versailles, who had started to draw a map of the royalhunting forests in 1764. Berthier completed his fathers mapin 1807 and is pointing to it in his portrait as Grand Veneurby J.A.C. Pajou, in grand costume , commissioned by theEmperor for the palace of Compigne. The court not onlyfought back, to regain power and privileges: it huntedback.

Napoleon I revived the courts autumn hunting trips toFontainebleau, suspended by Louis XVI after 1786 for reasonsof economy. He hunted there for about 50 days in the autumnsof 1807, 1809 and 1810. Some 10,000 people were lodged in thepalace and the town. As they had under Louis XVI, theatrecompanies came from Paris to perform in the palace theatre in theevening.

By 1812 the imperial hunt had a staff of 93 men, 115horses and 170 hounds, and cost about 445,000 francs ayear, compared to over 1 million under Louis XVI. Many ofits officials had served in the hunts of Louis XVI. Theyincluded Beauterne, porte-arquebuse of the King and theEmperor; Bongars, page de la vnerie ; and others. Theirhunting skills were more important than their politicalloyalties.

Napoleons marriage to the Archduchess Marie-Louise in1810 was an apogee of court life in France: they processedfrom the Louvre to the Tuileries palace, through theNapoleonic equivalent of the galerie des glaces of Versailles,the grande galerie of the Louvre, hung with picturestaken from conquered monarchs, past 4,000 cheeringParisians in court dress. Thereafter, as Pierre Brandahas shown, Napoleon devoted more time to traditionalroyal occupations such as attendance at mass, the huntand the theatre (100 plays were performed at court in1810).

NewYork

NewYork