The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

To Paris friends

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all those who have helped him with this book, in particular:

Olivier Aaron, Robert Alexander, Sheila de Bellaigue, Zeenie Bonifacio, Micheline Boudet, Anthony Bourne, Prince Gabriel de Broglie, Marie-Franoise Brizay, Caroline Butler, Franois Callais, Cirillo Camara, Baron de Cassagne, Edward Corp, William Dalrymple, Frdric Didier, Fram Dinshaw, Jane Dormer, Emmanuel Ducamp, Olivier Gabet, Ren and Batrice de Gaillande, Jean-Louis Gaillemin, Didier Girard, the Knight of Glin, Pat Gomer, David Higgs, Niall Hobhouse, Mira Hudson, Anne Hurley, Eardley Johnson, Sue, Ossama and Nur Kaoukgi, Manuel Keene, Neil Kent, Randal Keynes, Caroline Knox, Mrs Laing, Richard and Daphne Lamb, Katherine de Leusse, Mrs Bulwer Long, Maxwell Lowe, Thomas de Luynes, Jacques Mallattier, Mlle Marchant, Pippa Mason, Giles McDonogh, Bernard Minoret, Shaaker Mohamed, Joy Moorhead, Mrs R.S. Mortimer, Laure Murat, Gay Naughton, Andr Nieuwazny, Constantine and Nicola Normanby, Patrick OConnor, Dr Sylvia Ostrova, Jacques Perot, Daniel-Georges Polliart, Michel Poniatowski, Alexandre Pradre, Jane Preston, Vicomte de Rohan, Comte Jean de Rohan-Chabot, Baronne Elie de Rothschild, Grard Rousset-Charny, Francis Russell, Ian Scott, Dr H. Smiskova, The Hon. Mrs Townshend, Bruno Villien, Christopher Walker, Adam Zamoyski, and the staffs of the Bibliothque Nationale, the London Library and the British Library.

He is particularly grateful for their comments on the manuscript to Roger Hudson, Caroline Knox, Metin Mnir, Fouad Nahas and, above all, Howard Davies.

Nous nous estimerons heureux davoir prsent au Voyageur tous les objets dignes de son admiration ou de sa curiosit dans une Cit dont la magnificence rivalise avec celle de lantique Thbes; le luxe, le got pour les sciences et les arts avec Athnes; et qui domine sur lEurope, comme Rome, lorsquelle et conquis lempire du monde!

F.-M. Marchant, Le Conducteur de ltranger Paris, March 1814

Death of an Empire: Europe takes Paris

MarchJune 1814

Cest la Ville de Paris quil appartient dans les circonstances actuelles dacclrer la Paix du Monde lEurope en armes devant vos murs sadresse vous.

Proclamation of Marshal Prince Schwarzenberg, 31 March 1814

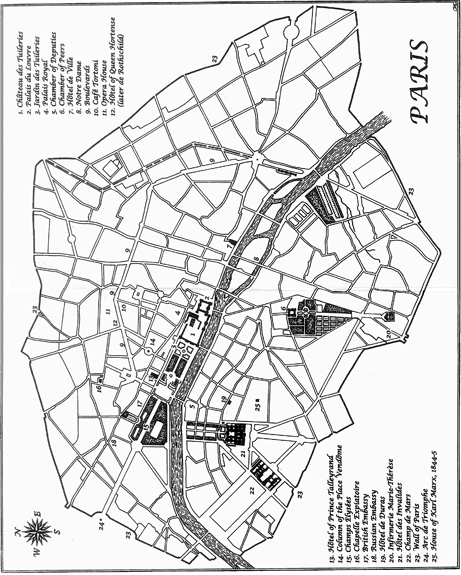

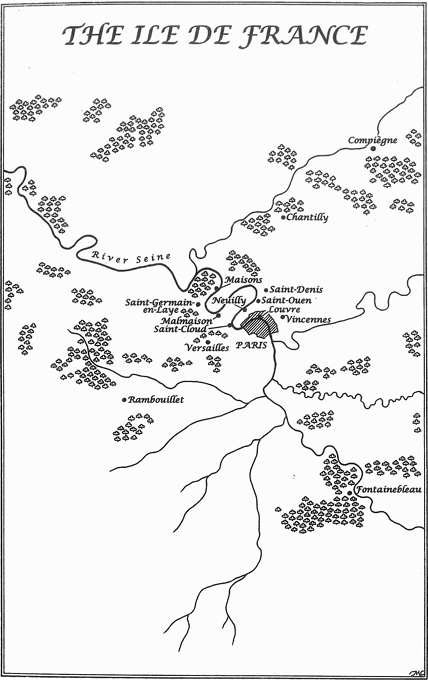

T HE NIGHT WAS clear and still; there was little movement in the streets. From the heart of the city Parisians could see the campfires of the enemy army on the surrounding hills and listen to the strange sound of Russian music. For the first time in its eight centuries as capital of France, Paris was besieged by a foreign army. The shock was all the greater given that, in the previous twenty years, under the Republic and the Empire, French soldiers had marched in triumph into almost every city in Europe, from Lisbon to Moscow. In 1811 the French Empire, under Napoleon I, had covered half the continent, from Hamburg to Rome, from Brittany to Dalmatia.

The buildings of Paris reflected its European empire. The Muse Napolon in the Louvre was filled with the spoils of war, seized from churches and palaces in Italy, Belgium and Germany, or extracted from Frances vanquished foes on the grounds that their rightful place was not with slaves but in the bosom of a free people. Among the loot were Rubens Descent from the Cross, removed from Antwerp cathedral; Raphaels St Cecilia from Bologna; Veroneses Marriage at Cana from Venice; and statues such as the Venus de Medici and the Apollo Belvedere, taken from Florence and Rome respectively. Archives from Vienna, Simancas and the Vatican had been removed to the Archives Impriales in the rue du Faubourg du Temple. The Cardinals too had been taken from Rome to Paris, after the imprisonment of the Pope and the annexation of the Papal States in 1809.

But the retreat from Moscow in 1812 and, even more, the Emperors defeat by an army of Russian, Austrian and Prussian soldiers at the Battle of the Nations outside Leipzig in October 1813 had been the beginning of the end. Since Leipzig Paris had been filled by dread of impending cataclysm. The only news that could be trusted was the location of the Emperors headquarters, as reported in his war bulletins, while he darted across the plains east of Paris at the head of an army of 50,000, trying in vain to block the advancing torrent of Russian, Austrian and Prussian soldiers. The Russian troops, enraged by the French invasion in 1812 and the burning of Moscow (in reality ordered by their own government), were said to know only two words of French: brler Paris.

At the end of March the streets of Paris had been made impassable by the arrival of peasants fleeing the fighting, bringing their cattle and carts laden with relations and possessions. The shouts and groans of frightened animals and people were deafening. Soldiers and cannon leaving for the battlefield crossed more files of carts piled with allied prisoners. Wounded French soldiers crawled haggard and emaciated through the streets of Paris demanding money, or simply lay down to die.

Lunatics were driven out of asylums, patients out of hospitals, to make way for the wounded. So many died that they had to be buried in mass graves to avoid a typhus epidemic. Other corpses were thrown in the Seine. According to Thomas Richard Underwood, an English artist who had lived in Paris as a prisoner on parole since the resumption of war between Britain and France in 1803, the number of dead bodies seen, either floating down the river or stranded on the banks was immense and exhibited an appalling spectacle. To reassure Parisians that the soldiers corpses had not contaminated the Seine, which was the citys main source of drinking water, two professors and the Dean of the Paris Faculty of Medicine were persuaded to publish a statement that the continued fluctuation and change of water destroyed all putrescence and that the fluid was consequently harmless.

* * *

The Napoleonic Empire had internal as well as external enemies. One of the most influential was the celebrated former bishop and revolutionary politician Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, Prince de Bnvent. Although in personal disgrace with the Emperor owing to his opposition to French expansion in Europe, as Vice-Grand Electeur he remained at the summit of the Empires official hierarchy. On 6 March he had sent a royalist, the Baron de Vitrolles, to allied headquarters in the east of France, with a letter written in invisible ink. Vitrolles mission was to reveal the strength of hostility to Napoleon in Paris and to urge an allied advance on the city.

Both the British and Russian governments had long helped finance the activities and propaganda of the exiled Bourbon pretender Louis XVIII, younger brother of Louis XVI. In his efforts to find a haven safe from the advancing French armies, he had spent the last twenty-three years on an odyssey around Europe from Germany to Verona, back to Germany, on to Mittau in Russia, Warsaw and finally England, where he lived from 1807 to 1814. Britain and Russia encouraged the distribution in France of his printed Declaration of Hartwell (his residence near Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire between 1809 and 1814), promising peace, stability, freedom and an endorsement of the post-revolutionary administrative settlement and property distribution. Madame de Marigny, sister of the great writer Chateaubriand whose works Le Gnie du Christianisme (1801), Les Martyrs (1809) and Itinraire de Paris Jrusalem et de Jrusalem Paris (1811) had spearheaded the Catholic revival in France, wrote in her diary on 17 and 20 March that the Kings declaration was being thrown into streets and shops, that the police were tearing it off the walls, that the Bourbons were talked of more than ever and that there was no news from the Emperor. He was leading a last desperate campaign to the south and east of Paris, hoping to split the advancing allied armies and defeat each section in turn.