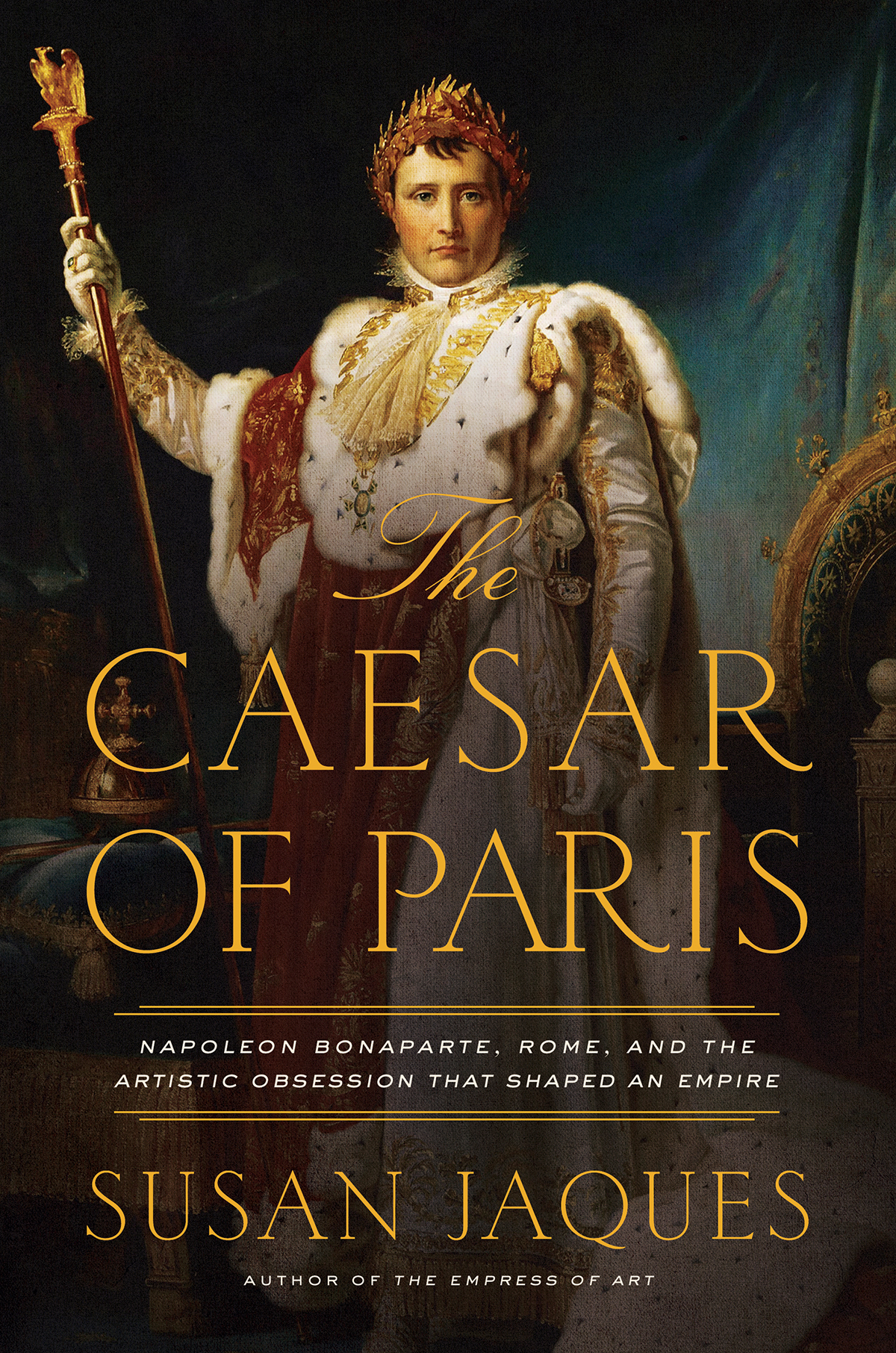

The

CAESAR

OF PARIS

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE, ROME, AND THE

ARTISTIC OBSESSION THAT SHAPED AN EMPIRE

SUSAN JAQUES

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

For Doug, to another thirty-four years

I am of the race of the Caesars, and of the best of their kind, the founders.

Napoleon Bonaparte

A s a young boy growing up on the island of Corsica, Napoleon Buonaparte begged his older brother to switch places with him in a mock combat pitting Romans and Carthaginians. The skinny youngster couldnt stand being on the losing side.

In May 1779, the nine-year-old arrived as a scholarship student at the Brienne military college in the Champagne region, speaking a Corsican dialect and bad French. Napoleon escaped his classmates bullying by reading, especially biographies of antiquitys great military commanders. His fascination with antiquity continued at the Military Academy in Paris. Napoleon was so well versed in Greek and Roman history that Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli told him: There is nothing modern in you; you are entirely out of Plutarch.

Early in his career as commander of the Army of Italy, Napoleon looked to his ancient heroes for military strategy. Caesars principles were Hannibals, and Hannibals were Alexanders: keep your forces together, dont be vulnerable on any front, strike very fast with full strength on a given point, he told his officers during the Italian campaign. The Egypt campaign was a military failure, but Napoleon cleverly spun it into a political and cultural victory. The French army was promoted as a successor to the Roman legions; the Egyptian Revival style became the rage in decorative art and architecture.

Antiquity exerted an equally powerful influence on Napoleon off the battlefield, where he waged a parallel campaign. After returning from Egypt, Napoleon took advantage of Frances power vacuum and staged a coup, replacing the corrupt Directory regime with the Consulate, named for a Roman institution. Just as Romes Caesars returned from campaigns with spoils of war, Napoleon brought wagonloads of art back to Paris from his military victories. Napoleon most prized the antiquities, many stripped from the Vatican. As Alex Potts puts it, the exhibition of Napoleonic war booty in Paris was a cruder version of the ancient Romans giving distinction to the ideal statuary of ancient Greece.

Tellingly, Napoleon gave the famed actor Franois-Joseph Talma advice on how to play Nero in Racines Britannicus and Julius Caesar in La Mort de Pompe. Emperors arent like that, the first consul told the star after seeing his performance as the notorious Roman emperor.

Napoleon soon cast himself in the real-life role. In May 1804, the Senate proclaimed the thirty-four-year-old emperor, bringing the French Republic to an end. Napoleon invited Pope Pius VII to officiate at his December coronation, then shocked everyone by crowning himself. As he famously told a confidant, I have dethroned no one. I found the crown in the gutter. I picked it up and the people put it on my head. Two years earlier, Napoleons Concordat with the newly elected Pius VII reestablished the Catholic Church in France. But the rapprochement did not last long.

The battle for control of the Catholic Church was just one of Napoleons obsessions with Rome. As the repository of 2,500 years of art and architecture, Rome had become Europes cultural capitala magnet for painters, sculptors, tourists, and archeologists. During his fifteen-year rule, Napoleon reshaped Paris into the new Rome, Europes culture capital. As Paris shined, the rest of Rome faded, first as the Roman Republic and later as a marginalized French dominion. Napoleon kept the uncooperative Pius VII under house arrest for nearly five years. During this time, he appropriated the Palazzo del Quirinale, the papal summer residence, turning it into his own lavish imperial palace.

Antiquity inspired all aspects of Napoleons imperiumfrom his short Augustus-like haircut to his choice for the symbol of his Empire, the eagle of Jupiter. From ancient Rome, he borrowed images and symbols of power and authority, along with its powerful rituals. Yet as Diana Rowell notes, Napoleon was not simply reinventing the Roman world; he and his entourage were simultaneously manipulating former Rome-inspired traditions to reinforce the impact of his own form of power over the past, the present, and the future.

Without any hereditary claim to rule, Napoleon sought legitimacy by associating himself with antiquitys greats and his rule with the great civilizations of ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Napoleons heroes were many and variable, writes Matthew Zarzeczny, his personal pantheon constantly changed with the circumstances. Just before his coronation, Napoleon added Charlemagne to the group, the Frankish king and military leader who unified medieval Europe after the Roman model. To drum up support for his planned invasion of England, Napoleon promoted William the Conqueror, the man behind the Norman Conquest, with an exhibition in Paris of the famous Bayeux Tapestry.

Travel continued to be a touchstone experience. Like his heroes Alexander, Julius Caesar, Augustus, and Charlemagne, Napoleon was rarely in his capital. Occupied on foreign campaigns, waging some sixty battles, the peripatetic ruler spent just two and a half years in Paris between 1804 and 1814. Extended visits to cities like Vienna, Berlin, Venice, and Genoa influenced Napoleons ambitious vision for Paris. Between battles, Napoleon dictated thousands of instructions for his projects to turn Paris into the rendezvous of all Europe.

A frequent recipient of these dispatches was Dominique-Vivant Denon, director of the Muse Napolon, who traveled with the Grande Arme overseeing art confiscations and curating the ever-growing collection. As Napoleons de facto culture minister, the urbane Denon also commissioned art to enforce his patrons heroic image. To lend authenticity to a series of monumental battlefield scenes, Denon embedded draftsmen in the army to take notes on everything from uniforms to topography. Denons A-list painters included Antoine-Jean Gros, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, as well as their teacher Jacques-Louis David.

In paintings, sculpture, medals, and porcelain, Napoleon was portrayed in the guise of Roman gods and as a modern Caesar. As Christopher Lloyd writes, his personal iconography is one of the most extensive ever created for an individual and is a perfect demonstration of the way in which art could be harnessed to political and military ambition.

A far less enthusiastic propagandist was the celebrated Italian sculptor Antonio Canova. Resentful of Frances treatment of Italy, Canova had a complex relationship with Napoleon. He designed the tomb of the patriotic Italian poet Vittorio Alfieri for Santa Croce in Florence, along with a funerary monument for Napoleons archnemesis, British admiral Horatio Nelson, yet kept a bust of Napoleon in his bedroom until his death. Dispatched to Paris twice to model portraits of the Bonapartes, Canova doubled as papal envoy. In 1815, Pius entrusted Canova with retrieving the Papal Statess stolen art in Paris, forcing a face-off with the wily Denon.

Like Romes emperors, Napoleon adorned his capital with heroic, monumental architecture inspired by surviving masterworks of ancient Rome. Declaring that Men are only as great as the monuments they leave, he ordered the construction of icons like the Vendme Column, the Arc de Triomphe, the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, and Temple to the Glory of the Grande Arme, todays Madeleine Church. Augustus boasted of building his Forum from the spoils of war; Napoleon too financed his building spree with indemnities from his many conquests.

Next page