Copyright 2018 by Rupert Christiansen

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: October 2018

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Names: Christiansen, Rupert, author.

Title: City of light : the making of modern Paris / Rupert Christiansen.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018012387 (print) | LCCN 2018033758 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541673434 (ebook) | ISBN 9781541673397 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Paris (France)History18481870. | Urban renewalFranceParisHistory19th century. | Public worksFranceParisHistory19th century. | Haussmann, Georges Eugene, baron, 18091891Influence.

Classification: LCC DC733 (ebook) | LCC DC733 .C483 2018 (print) | DDC 944/.36107dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018012387

ISBNs: 978-1-5416-7339-7 (hardcover), 978-1-5416-7343-4 (ebook)

E3-20180824-JV-NF

Prima Donna: A History

Paris Babylon

Romantic Affinities: Portraits from an Age 17801830

The Victorian Visitors: Culture Shock in Nineteenth-Century Britain

En mmoire de Claudine, Nicole, Danielle, et les autres chres filles au pair de mon enfance, qui mont inspir une ardeur romantique pour la ville lumire

A view of the foyer of Garniers Opra as it is today. (J OE V OGAN / A LAMY S TOCK P HOTO )

J ANUARY 5, 1875, WAS A winters evening during which Paris radiated all the glamour that had earned it a reputation as la ville lumire, the city of light. Tonight would be special: a brighter glow in its celebrated illuminations was caused by the ceremonial opening of a magnificent new opera house, designed by the architect Charles Garnier in a style of unabashed grandeur that continues to astound and delight today. The occasion of its inauguration drew hordes of rubberneckers to the streets as a pageant of officers of state, crowned heads, venerable nobles, and uniformed dignitaries paraded through the doors. A particular sensation was caused by the arrival of the lord mayor of London, emerging from a gilded fairy-tale coach robed in all the antique splendor of his office.

An artists impression of the foyer of Charles Garniers Opra on its opening night, January 5, 1875. (E VERETT C OLLECTION / B RIDGEMAN I MAGES )

The building had been under construction for nearly fifteen years at vast cost, with no expense spared on either materials or decoration. But for the moment, nobody cared about the budget sheet (several million francs over the original estimate, as is so often the case): a week before, Garnier had formally handed over the 1,942 keys to the management, and now the singers and dancers prepared to christen it in a lengthy program of operatic scenes and balletic divertissements. To a city addicted to excitement, scandal, and headlines, the novelty was all: as The Times of London reported, the opening of the Opra was the sole, the only topic which engages public interest and attention.

Garniers Opra, as seen from the Avenue de lOpra, circa 1880. (P RIVATE C OLLECTION / B RIDGEMAN I MAGES )

The show proved something of an anticlimax, dragging on interminably without aesthetic distinction. Exacerbated by opening-night panic and production problems, the scenery did not fit the space properly, and the stage management proved amateurish. The prima donna Christine Nilsson had withdrawn at the eleventh hour, as prima donnas tend to do, because of an indisposition. As the exasperated critic Lon Escudier wrote in his review, A corner grocers shop could have organized a more attractive artistic celebration. There were problems of protocol as well: so lengthy was the list of honored guests that Garnier, the genius who had fanatically devoted himself for over a decade to the creation of this wonder of the world, was assigned a seat in a box to the side of the auditorium on the second tier, an appalling snub that he brushed aside by choosing to remain in his office and continue working instead.

This was the publics first glimpse of the foyers where Garniers imagination had run free: gilded and mirrored salons, shimmering candelabra and marbled colonnades, ceilings covered with mosaics and frescoes, classical statuary, and flaming gas torchres, all enhancing a superb central stairwell that turned the ascending and descending audience into a spiraling spectacle far more impressive than anything that the clunking grand operas and silly, twittering ballets could display on stage. Patriotic hearts were exhorted to rejoice, and even the satirical weekly Le Sifflet responded to the call: Be proud of being French when looking at our Opra! Foreigners who come to visit this marvel will see that despite all our misfortunes, Paris is and always will be without rival.

Yet ultimately the significance of this opera house was not a matter of music, art, or even architecture. It was an ideologically charged symbol of Frances recent history and bruised national pride: an ambiguous monument to a triumph and a disaster that had started as one thing and ended as another.

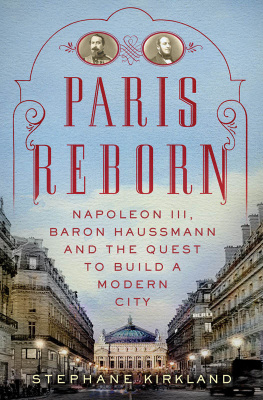

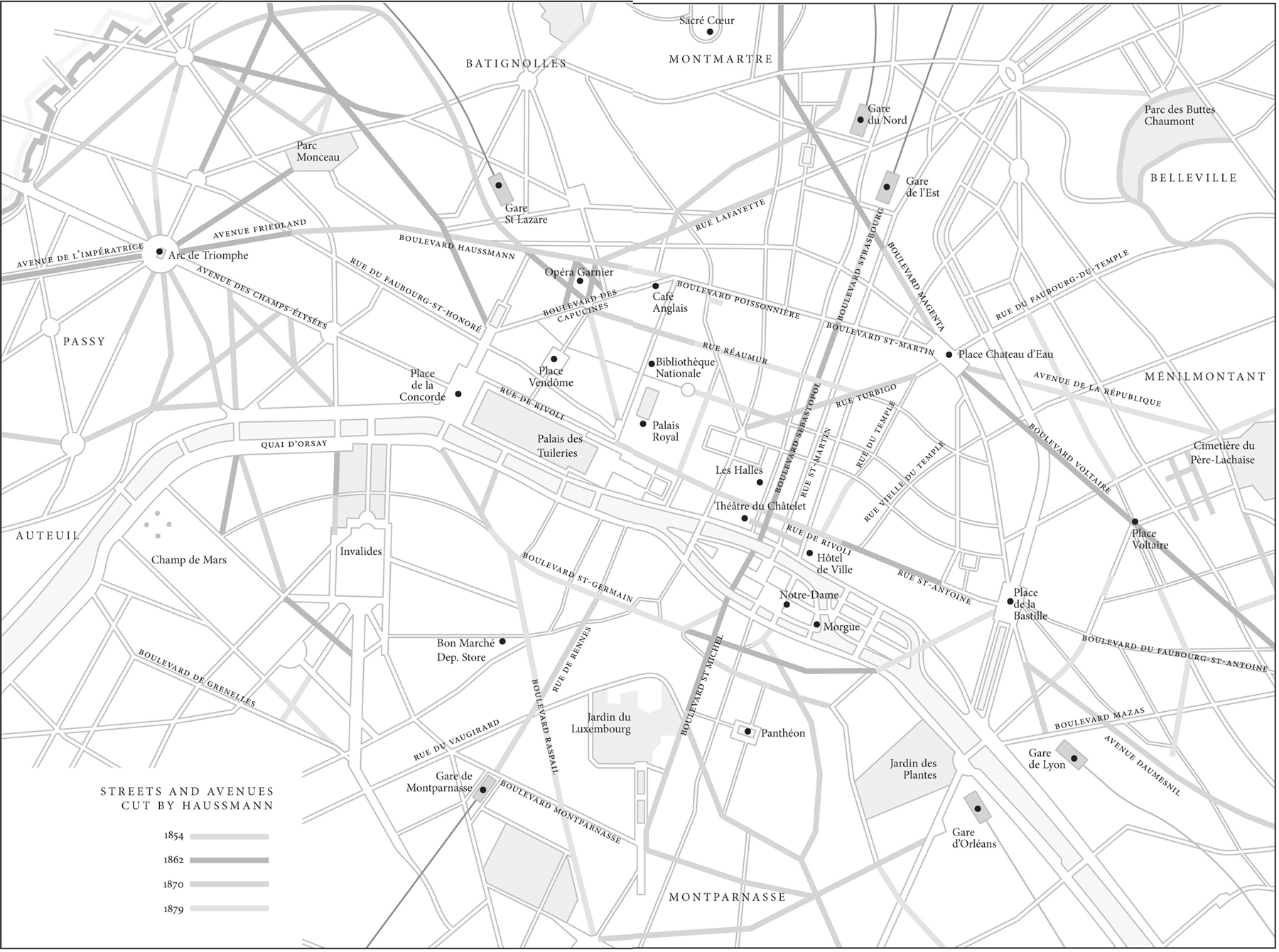

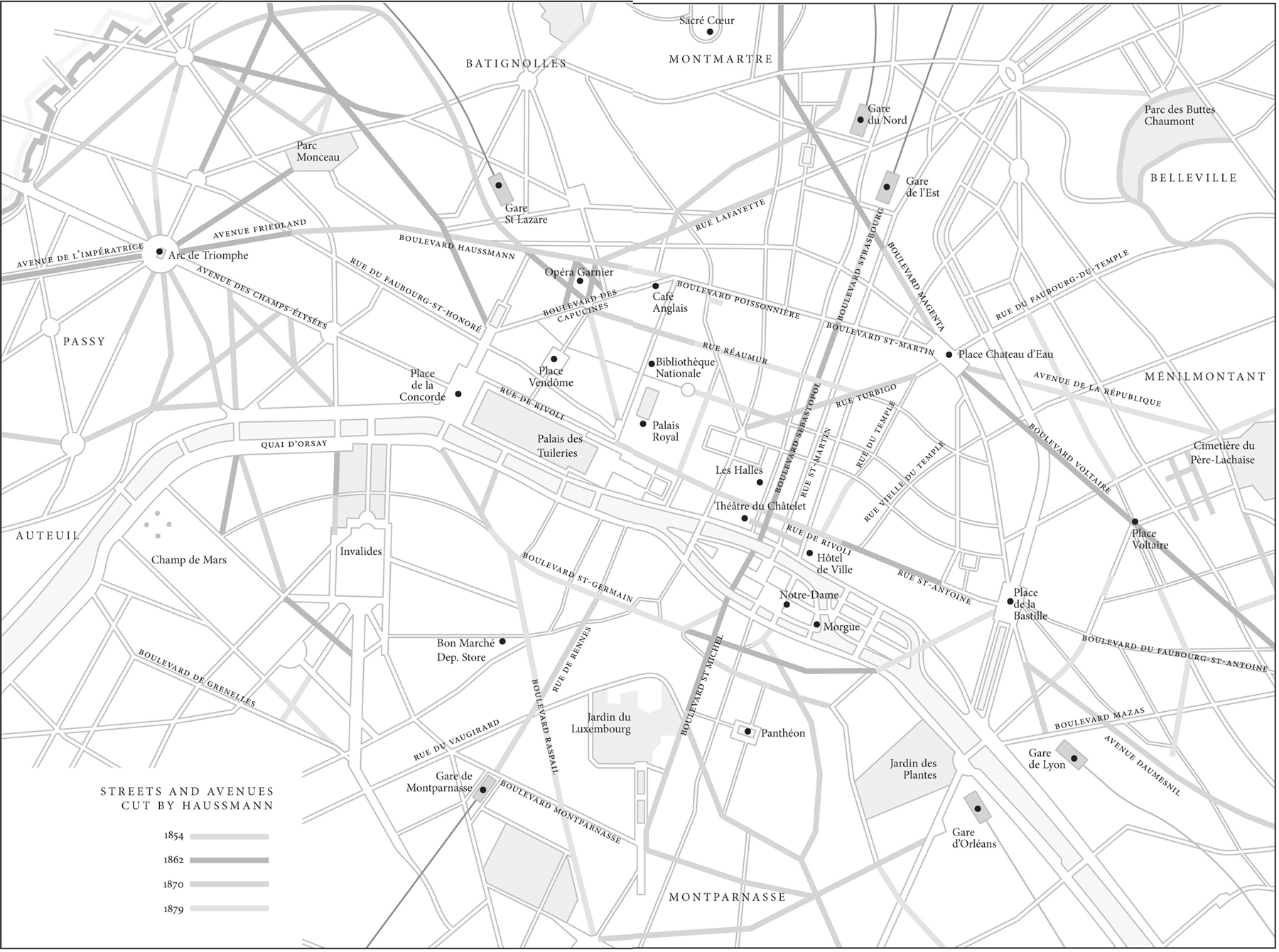

The project had originated as a key element of a vast, unprecedented strategy to redevelop the capitals center that was conceived by Louis Napolon, authoritarian ruler of France from 1852 to 1870, and executed by his fearsomely effective left-hand man and de facto mayor of Paris, Baron Haussmann. An opera house would be a focal point for a network of new streets, new private housing, new public buildings and monuments, new parks, new sewers, and even new city boundaries that ranks among the greatest experiments in urban planning ever undertaken.

But in 1870 the French had foolishly gone to war against Prussia and suffered a crushing and unexpected defeat. Louis Napolons regime, known as the Second Empire, had collapsed, and Paris had in consequence endured a long siege, followed by a revolt that resulted in the brief establishment of the socialistic Commune, suppressed by the new republican government through a swift massacre of perhaps 20,000 French citizens.