Sante - The Other Paris: The Peoples City, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Here you can read online Sante - The Other Paris: The Peoples City, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: France--Paris., Paris (France), year: 2015, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Other Paris: The Peoples City, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2015

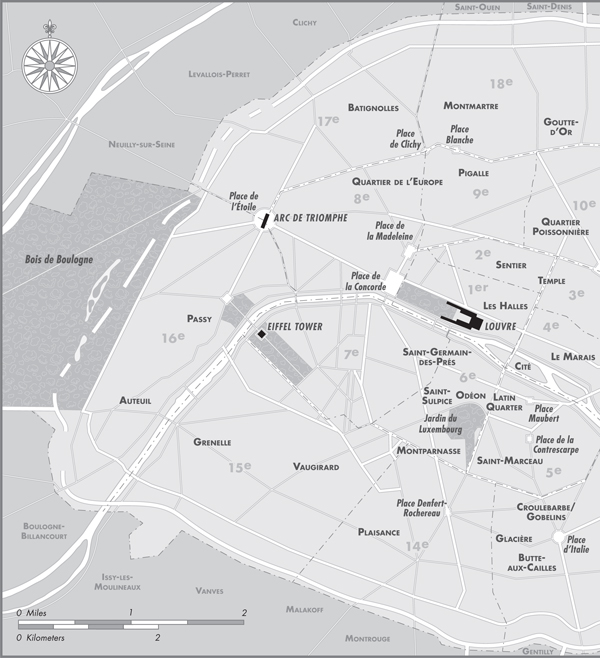

- City:France--Paris., Paris (France)

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Other Paris: The Peoples City, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Other Paris: The Peoples City, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

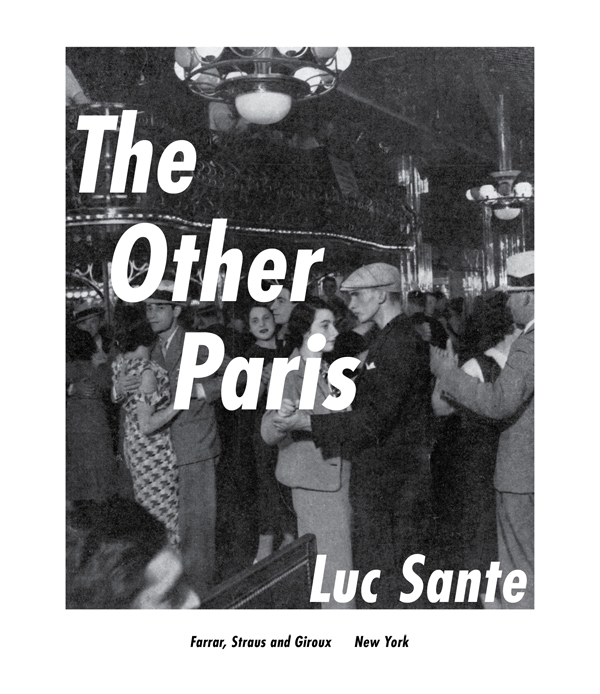

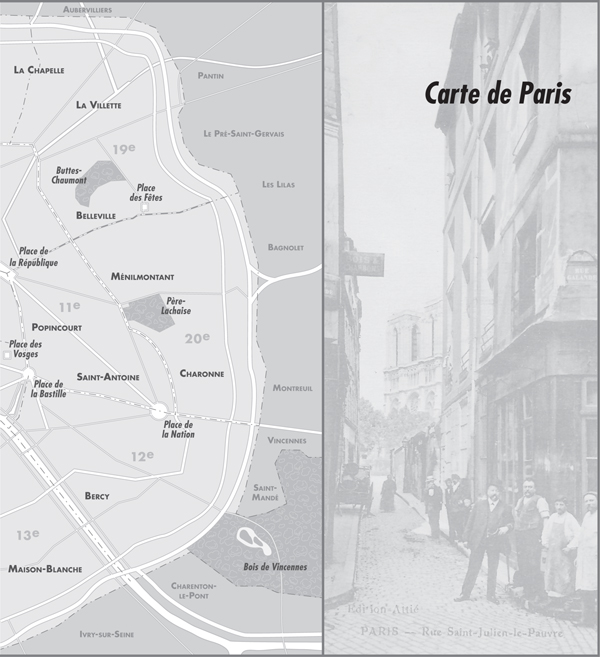

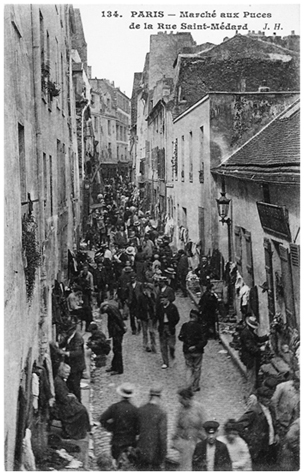

A trip through Paris as it will never be again-dark and dank and poor and slapdash and truly bohemian

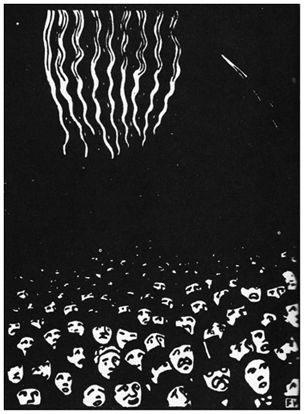

Paris, the City of Light, the city of fine dining and seductive couture and intellectual hauteur, was until fairly recently always accompanied by its shadow: the city of the poor, the outcast, the criminal, the eccentric, the willfully nonconforming. In The Other Paris, Luc Sante gives us a panoramic view of that second metropolis, which has nearly vanished but whose traces are in the bricks and stones of the contemporary city, in the culture of France itself, and, by extension, throughout the world.Drawing on testimony from a great range of witnesses-from Balzac and Hugo to assorted boulevardiers, rabble-rousers, and tramps-Sante, whose thorough research is matched only by the vividness of his narration, takes the reader on a whirlwind tour. Richly illustrated with more than three hundred images, The Other Paris scuttles through the knotted streets of pre-Haussmann Paris, through the improvised accommodations of the original bohemians, through the whorehouses and dance halls and hobo shelters of the old city.

A lively survey of labor conditions, prostitution, drinking, crime, and popular entertainment, and of the reporters, raliste singers, pamphleteers, and poets who chronicled their evolution, The Other Paris is a book meant to upend the story of the French capital, to reclaim the city from the bons vivants and the speculators, and to hold a light to the works and lives of those expunged from its center by the forces of profit.

Sante: author's other books

Who wrote The Other Paris: The Peoples City, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.