Table of Contents

ALSO BY LUC SANTE

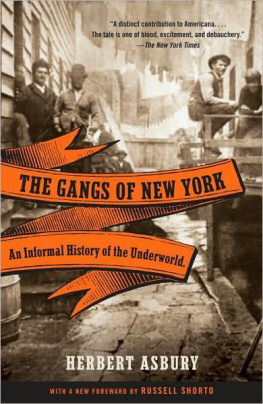

Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York

Evidence

The Factory of Facts

CO-EDITOR (WITH MELISSA HOLBROOK PIERSON)

O. K. You Mugs: Writers on Movie Actors

EDITOR AND TRANSLATOR

Novels in Three Lines by Flix Fnon

To Barbara Epstein

1928-2006

I had intended to dedicate this book to Barbara back when I thought she would live forever. She did more than just edit five of the best things herein; she formed me as a writer. The dedication was to have been a public thank-you note. I can only hope she had a glimmer of how much she meant to me.

Acknowledgments:

I would like to thank the editors who solicited, encouraged, and abetted the pieces herein (my apologies to those few whose names I have not retained): Tom Beller, Chuck Eddy, Anne Fadiman, Sean Howe, Andrew Hultkrans, Wendy Lesser, Greil Marcus, Susan Morrison, Annie Nocenti, Ed Park, Ann Philbin, Rob Polner, Joy Press, Jason Shinder, Paul Smart, Matt Weiland, Eric Weisbard, Sean Wilentz, and Rebecca Wilson; also thanks to Robert Christgau. Special thanks to Jonathan Galassi, instrumental in both the first and the last items in the collection. Very large extra thanks to Greil Marcus and to Francesco Clemente, as well as to Raymond Foye. Thanks as ever to Joy Harris. Big huge thanks to Yeti Mike McGonigal and Steve Connell for taking a chance on this book. And no end of thanks and love to Melissa and Raphael, my constant inspirations.

Most of the contents of this book have previously been published, often in somewhat different form and under different titles, in the following: My Lost City, I Is Somebody Else, The Invention of the Blues, The Hunger Artist, and The Perfect Moment in the New York Review of Books; A Riot of My Own in Mr. Bellers Neighborhood; The Bandit King in the New York Times (City Section); In a Garden State in The Nation; The Injection Mold in Granta;

Why Do You Think They Call It Dope? in High Times; Auld Lang Syne in the New York Observer; Strength Through Joy in Ulster Magazine; I Cant Carry You Anymore, Teenage History, and Getting By and Making Do in the Village Voice; The Detective in the Threepenny Review, The Department of Memory (first part) in Bookforum; The Department of Memory (second part) in Modern Painters; A Companion of the Prophet in The American Scholar; The Ruins of New York in Francesco Clemente: Palladium (Nrnberg: Verlag fr moderne Kunst, 2000); The Sea-Green Incorruptible in Americas Mayor, edited by Rob Polner (Soft Skull, 2005); I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say in The Rose and the Briar, edited by Greil Marcus and Sean Wilentz (W. W. Norton, 2004); The Octopus Bearing the Initials V. H. in Shadows of a Hand: The Drawings of Victor Hugo, edited by Florian Rodari and Ann Philbin (The Drawing Center/Merrell Holberton, 1998); The Clear Line in Give Our Regards to the Atomsmashers! edited by Sean Howe (Pantheon, 2004); and The Total Animal Soup of Time in The Poem That Changed America, edited by Jason Shinder (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006).

Kill all your darlings.

writerly advice attributed to William Faulkner

Et on tuera tous les affreux.

Boris Vian, title of book

INTRODUCTION

by Greil Marcus

As I read through the pieces Luc Sante has collected here, the phrase that came to mind was hard-boiled. As in a hard-boiled detective, poking around in a place where something happened, knowing that the clues will be less obvious in a neat, spotless room where it seems inconceivable that anyone was killed there than in a room so tossed by violence it seems inconceivable somebody wasnt. Not that this book, despite its title, has much to do with mayhem in any conventional mannerunlike Santes Low Life and Evidence, or New York Noir and The Big Conthe last two, a collection of photos from the New York Daily News and a reissue of David W. Maurers 1940 study of con artists, merely introduced by Sante, but with such immediacy you feel his voice all through their pages. Its that a feeling of suspense is just as presentor more present. With the work for which Sante is best known, he writes as a historian, and the suspense is in the past. Herewhere Sante is writing about New York City, cigarettes, drugs, and his own earlier years, but most carefully and intensely about music, painting, photography, and poetrythe suspense is active on the page, or even pushed into the future. Here, to be hard-boiled means to go in ready to get the truth out of the suspect, knowing that the crunch may come when the suspect begins to get the truth out of you.

When you truly put yourself face to face with a piece of art, it will interrogate you as surely as you might flatter yourself to think that you have interrogated it, because unlike an ordinary crime, a work of art is never finished. No matter how complete it might appear to the world at large, when a writer confronts a book or a painting or a song, nothing is settled and anything can happen. You can make the work new, or it can leave you exposed in all your stupidity on your own page.

Its all in the tone, which for Sante means a quiet, calm, forceful attempt to get inside those people, places, artifacts, and memories that attract him, with a commitment to the subject at hand that is as passionate as it is modest. There is no hyperbole, or critical hysteria: there is no panic in the face of the writers inability to make a melody, an image, or a patch of words give up its secrets. Modesty is part of what it means to be hard-boiled: an acceptance that some secrets will never be given up. The tone comes out of empathy, on the one handempathy for the perpetrator, the artist or the art work, the person or the act rememberedand it produces respect, for the reader, for the person who has to be brought into the story, the writer making his own story unfamiliar to himself in order to open it up to others. Everything seemed possible then, Sante writes of how Bob Dylan, in his book Chronicles, Volume 1, situates himself early in his career, but Sante doesnt rest with the clich, which is to say he doesnt insult either Dylan or his reader with it. He redeems the clich, returns it to real speech, by making it speak: Everything seemed possible then; no options had been used up and nothing had yet been sacrificed.

The tone demands incisiveness and concision, a sense of what to leave in and what to leave out, as with Santes startling argument that the bluesthe now-familiar three-line verse, with its AAB rhyme scheme and its line length of five stressed syllableswas invented, by a single person, on a certain day, in a certain place. There is a sociological setting that makes the notion seem ordinaryThe origin of the blues occurred close to our time, within a historical corridor that makes it possible to place it among the early manifestations of modernismbetween the automobile and the airplane, and not long after the movies, radio transmission, and cylinder recordingsa setting that only seems sociological, because it is in fact moving toward a setting where sociology cannot go. If the invention of the blues took place on the broad, visible terrain of modern technology, it also, Sante says, appeared, and in an uncanny sense remained, in an inaccessible back street of history, so that we dont know who or when or how or why, just that it happened. And then, with an economy and a cold eye worthy of Twain, or Hemingway, or Chandler, a story: The very success of the invention must also have mitigated against anyone knowing who was responsible. Even if a front-porch guitarist was responsible, rather than an itinerant songster, it is easy to imagine that within twenty-four hours a dozen people had taken up the style, a hundred inside of a week, a thousand in the first month. By then only ten people would have remembered who came up with it, and nine of them werent talking.