Lucy Sante - Nineteen Reservoirs

Here you can read online Lucy Sante - Nineteen Reservoirs full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: The Experiment, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Nineteen Reservoirs

- Author:

- Publisher:The Experiment

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nineteen Reservoirs: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nineteen Reservoirs" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nineteen Reservoirs — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nineteen Reservoirs" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

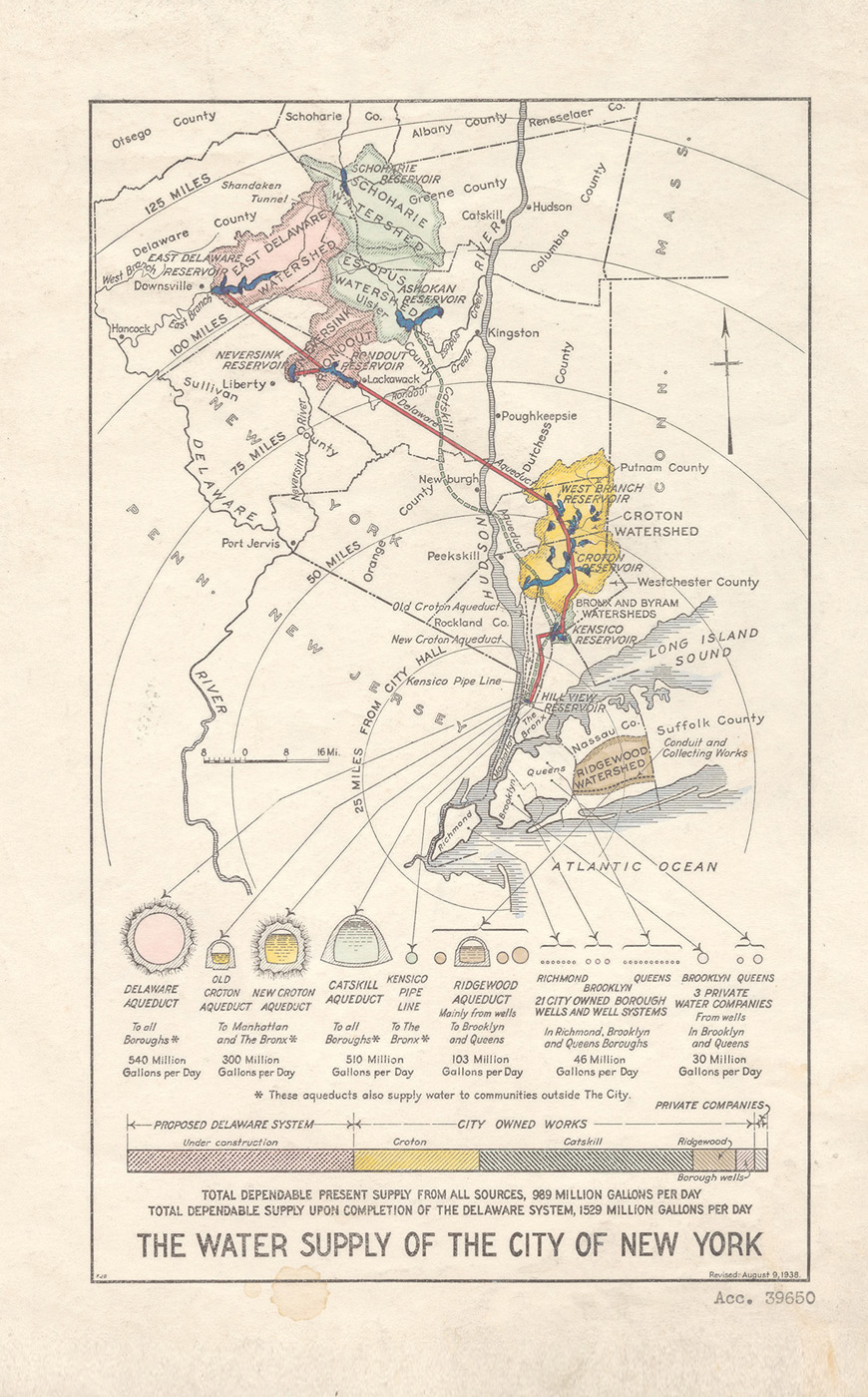

The New York City water supply system, 1938

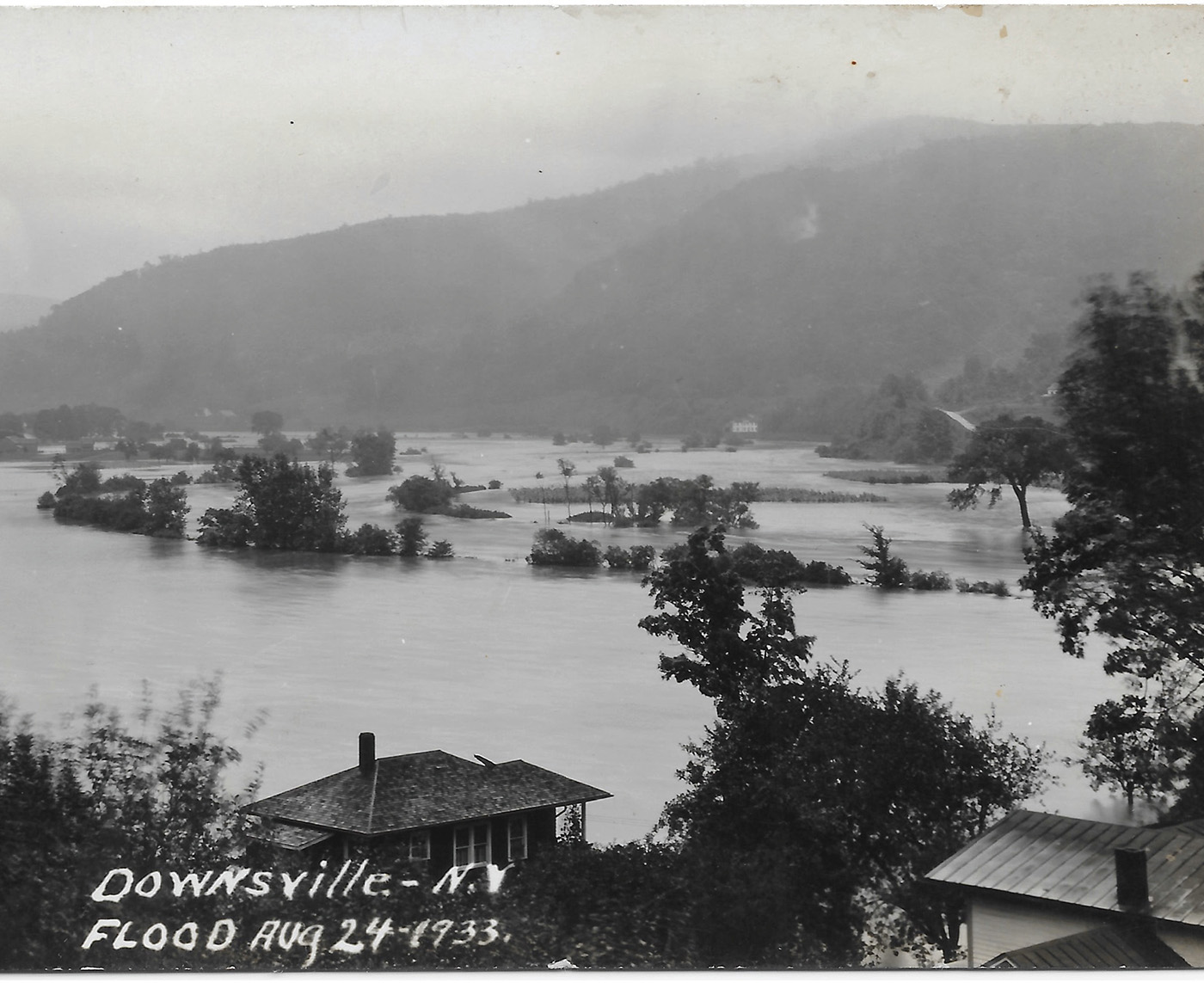

Downsville flood, postcard, 1933;

Surveyors at Bonticou Crag determining the future path of the Catskill Aqueduct, November 1906

High-pressure hydrant test at Union Square, New York City, 1908

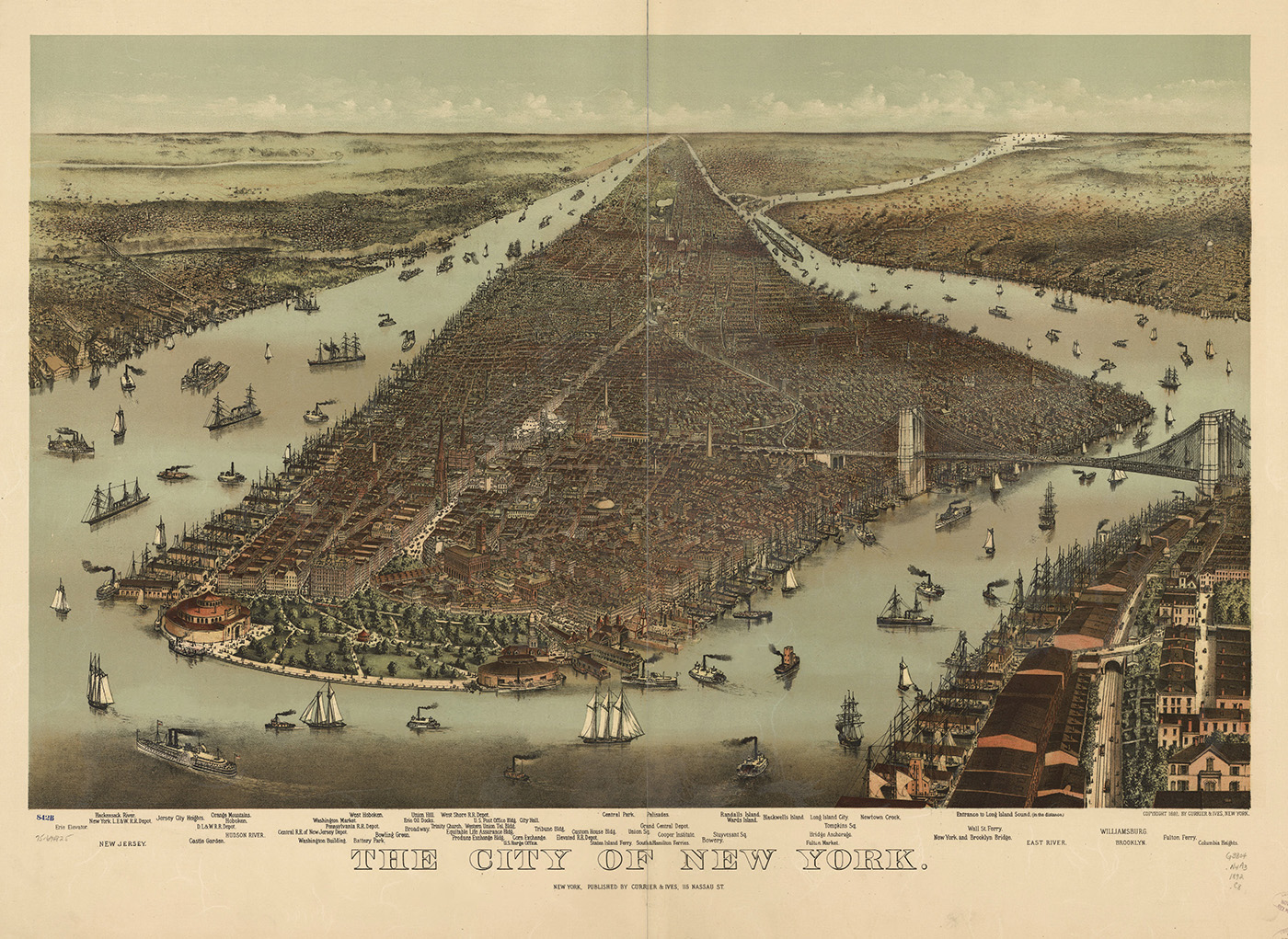

Prospective map showing a birds-eye view of points of interest in New York City, 1892

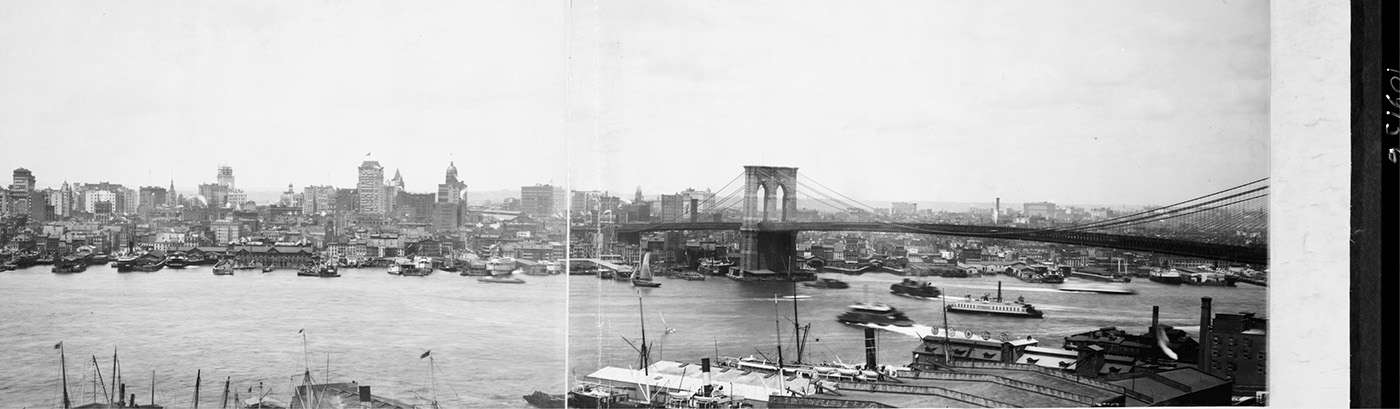

The city and harbor of New York, 1896

New York City became one of the worlds great cities in large part because it is one of the worlds great natural harbors. From Manhattan Island to Staten Island to Long Island (read: Brooklyn and Queens), the place is surrounded and permeated by water. But none of it is potablenot the East or Harlem Rivers, which are effectively arms of the sea, and not the Hudson River, which in its lower reaches also becomes a tidal estuary, combining sea and fresh water in a varyingly brackish mix for at least the lower half of its 153-mile course, from its mouth in New York Harbor back up to the Federal Dam in Troy near the center of the state. For drinking, cooking, and washing purposes, the first European settlers were able to tap the islands ponds, streams, and springs. But an ever-expanding population eventually drained such resourcesthose not already tainted by pollution or disease. And the population galloped on relentlessly: From a thousand or so Dutch nationals in 1650, fourteen years before the British invasion and seventeen before the first wells were dug, the number had jumped to nearly 25,000 by the time of the American Revolution. By 1800, it was 60,000. It was then that the citys political and financial powers recognized a crisis and understood that water would have to be brought in from outside the city.

Mulberry Street, New York City, circa 1900

It was the first of many such realizations and interventions over the succeeding century and a half. Once the idea of importing water had seated itself in the public mind, it was hard to dislodge, for without more reliable sources, the city could not survive. The moral justification for the seizure of water belonging to other regionsthe landowners were always compensated, but under the terms of eminent domain they were not permitted to refusewas invariably that the needs of the many overrode the rights of the few. That was true as far as it went: More and better water would benefit immigrants, freed slaves, disabled veterans, the chronically ill, and the destitute in addition to the middle and upper classes. But although such arguments were politically convenient, the architects of New Yorks water-importation schemes across the decades seem to have been rather more concerned with the needs of business. The requirements of the great mass of people reached their ears only on occasions when the city was in the grip of what was called a water famine, when pipes lacked sufficient pressure to serve the upper floors of buildings, making the whole metropolis a fire hazard. It follows that politicians and their commissioners tended to think of the extramural regions from which they proposed to pump as essentially uninhabited, since no industry was occurring there. Their attitude, in a word, was colonial.

Street scene in the Ashokan district near Browns Station, postcard, circa 1907

The people whose land was taken reacted with disbelief, sorrow, anger. That land might have been in their families for generations, might have been the familys sole support, might have been the only home theyd ever known. The city decreed and mobilized and condemned properties for seizure without asking residents permission, found all sorts of legal subterfuges for denying the value of their fields and homesteads as established by expert witnesses, lowballed every estimate, treated them with distant contempt. Since the politicians and commissioners were not running for office upstate, they felt no need to package their enterprise as a humanitarian mission; they spoke in numbers and legal precedents. There was already a long history of mistrust between the city and its rural neighbors, who felt themselves sidelined in the political discourse that traveled between Manhattan and the state capitol in Albany: The small farmers and small-town business owners to the north of the great city were routinely caricatured in the press as apple knockers and rubes, were exploited by prosperous urbanites who built summer homes in choice locations and then prosecuted trespassers. That these same remote and implacable beings were now proposing to drown pastures, raze villages, usurp water, and even decree how remaining land should be worked was a shock if not exactly a surprise.

You could say that the very idea of diverting water from somewhere else to benefit the inhabitants of New York City represents a version of the trolley problem. In that ethical thought experiment, you are standing by the switch as a railcar comes barreling along, headed for five people tied up on the tracks. You can pull the lever and turn the car onto a branch line, but there you see one person tied up. Do you do nothing and permit five deaths, or act and cause one? Do you do nothing and impose a water famine on a teeming city, or do you pull the lever and shift the onus onto much more sparsely populated rural areas? There is no satisfactory solution to this dilemma, and New York City had no real choice.

Throughout the nineteenth century, as multiple plans were suggested for bringing in water, those that avoided imposing on the countryside tended to lie on the farther shore of practicality. Unrealized schemesall of them soberly submitted and consideredranged from an 1834 proposal to dam the Hudson at Christopher Street in Greenwich Village to one in 1950 for damming it at Haverstraw in Rockland County 40 miles north, a 1905 plan for a pipeline from the Great Lakes, and a 1966 scheme to dam Long Island Sound and turn it into a freshwater lake. The more realistic ideas all involved tapping upstate watercourses, although these raised their own momentous engineering challenges, not least of which was the basic question of how to convey water to the city through many miles of diverse topography and shifting geological properties, let alone the problem of getting it across the broad and deep Hudson.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Nineteen Reservoirs»

Look at similar books to Nineteen Reservoirs. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nineteen Reservoirs and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.