Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Mimi

Sire, I am from the other country.

Ivan Chtcheglov

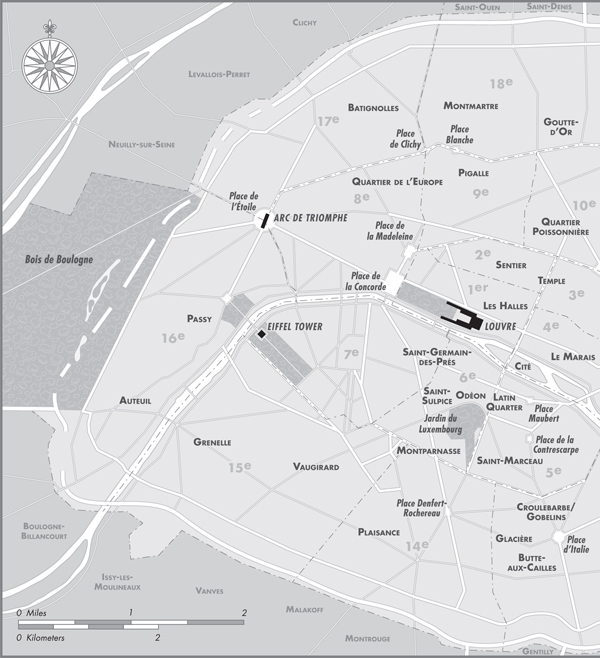

In Julien Duviviers 1937 film Pp le Moko , set in the Algiers casbah, the two leading characters are waxing nostalgic about their native city. Gaby (Mireille Balin) was gently reared, while Pp (Jean Gabin) is working-class.

Gaby: Do you know Paris?

Pp: Its my village, Rue Saint-Martin.

Gaby: The Champs-lyses.

Pp: The Gare du Nord.

Gaby: The Opra, Boulevard des Capucines.

Pp: Barbs, La Chapelle.

Gaby: Rue Montmartre.

Pp: Boulevard Rochechouart.

Gaby: Rue Fontaine.

Both: Place Blanche!

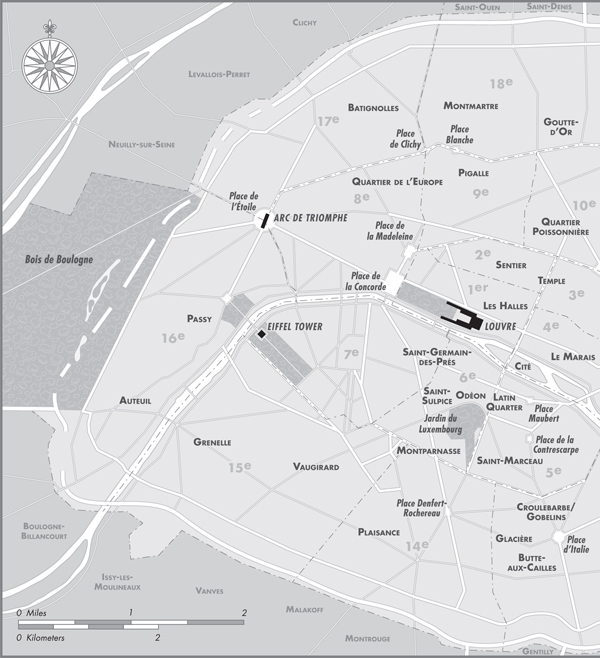

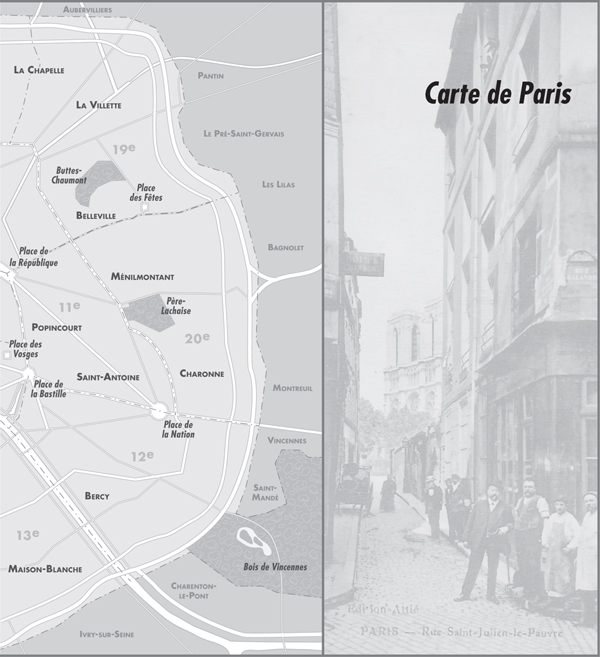

She names places in her city, he names places in his, and then they both agree on a square that straddles the borderthe site of the Moulin Rouge and the place where the honky-tonk of Pigalle locks eyes with the gentility of the Quartier de lEurope. Gabys list defines the top edge of the pie slice of western Paris, a quarter of the whole at most, that then housed the gentry: the northwesterly course of Rue Montmartre that is picked up by Rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette and then Rue Fontaine, and then goes on to merge into Avenue de Clichy. If she had been thorough she might have mentioned the other leg, on the Left Bank: Boulevard Saint-Germain, Rue de Svres, Avenue de Suffren. Pps list is far less comprehensive, but thats at least in part because in 1937 there was still so much more of his city than of hers.

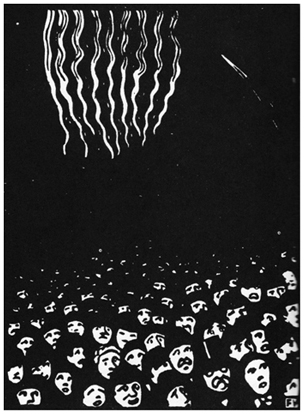

Mireille Balin and Jean Gabin in Pp le Moko, 1937

This book will not be much concerned with Gabys city. It has changed far less, for one thing. It retains the greatest concentration of money and power, and in that way common to old-money neighborhoods in many cities, it has probably preserved more of those small businesses, cafs, and such than have the more vulnerable neighborhoods elsewhere, because the rich have the power to save the things they love. That wedge of western Paris has changed primarily in that its composition now includes not just the old families and the nouveaux riches but also a significant number of foreign and often absentee property owners who invest in a Paris flat the way they might buy art and warehouse it. That attitude might almost make you think fondly of the old families, who at least are or were connected to the citys soil and history. But then you might recall how consistently inimical the western districts have been to the rest of the city over time, how they made common cause with the Prussians against the Commune in 1871; called for the extermination of the Communards, including women and children, during the Bloody Week in May of that year; and in 1938, after the Popular Front, acclaimed Hitler in the cinemas of the Champs-lyses at twenty francs a seat, while even fashionable ladies joined in shouting the slogan Communists, get your bags; Jews, off to Jerusalem. It is no coincidence that the Gestapo office on Rue des Saussaies and the headquarters on Rue Lauriston of its French counterpart, the Carlingue, were both situated within that triangle.

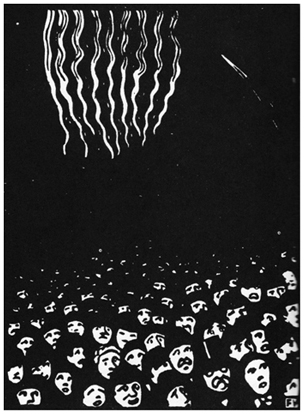

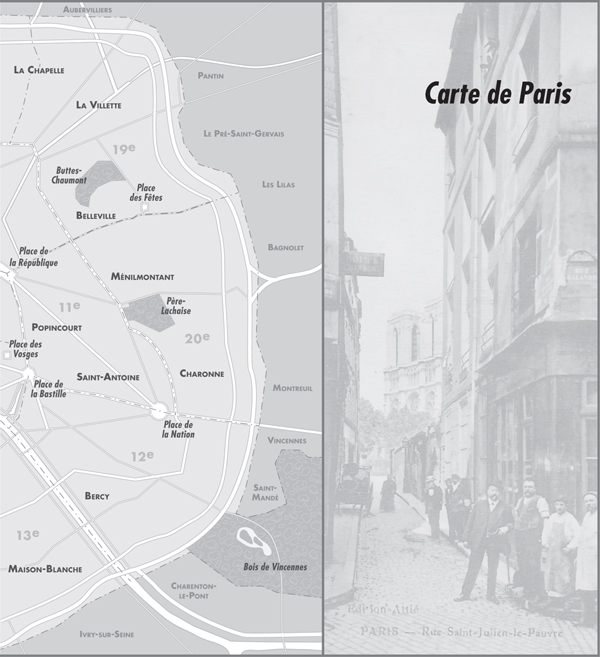

Fireworks. Illustration by Flix Vallotton, 1902

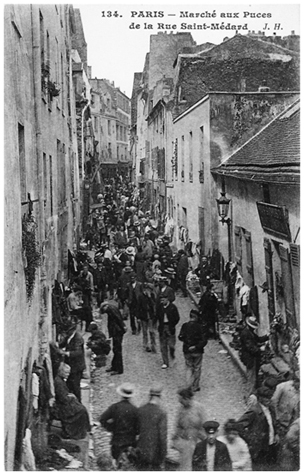

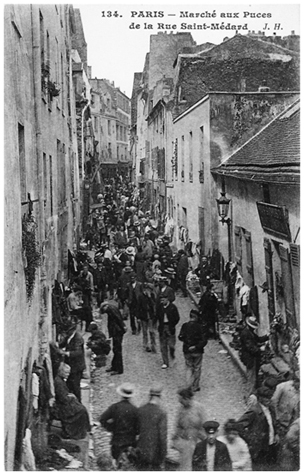

But if Gabys city was all demure white faades, discreet traffic, and well-mannered exchanges, Pps was undeniably rougher. The marketplace of the street brought all types to the fore, and they did not necessarily speak correctly or measure their tones or clean themselves up; they might not have wished you well. And the streets themselves held as many gaping eyesores as they did the sort of charmingly weathered houses you admire in Atgets pictures. You can read Georges Cains description of the March des Patriarches, the now long-gone flea market around the church of Saint-Mdard in the Fifth Arrondissement, and judge that it reflects the authors class bias, as an antiquarian and museum curator slumming around while looking for forgotten architectural treasures: Tumbledown hovels sheltering miserable enterprises: resellers of nameless objects, dealers in rags, vendors of dust. A side of beef is being butchered alongside a big factory wall that looks like a prison. And everywhere the air is poisonous with sulfuric acid, kippered herring, and cauliflower. But nearly the same tone appears thirty years later, in a description of the area near Place des Ftes, in the Nineteenth, by Eugne Dabit, the most self-consciously proletarian of writers:

A shoelace vendor, his face ravaged, looks as if hes wearing a mask with a fake beard and red cloth lips. At the market on Rue du Tlgraphe a woman selling thyme repeats in a piercing voice, Give work to the blind. People drag themselves from job site to job site, picking up wood, and from street to street, picking up rags; others are trusties or nightwatchmen. On their days out, the guys from the shelters, in their rough blue uniforms, tentatively hold out their hands, hoping to pick up enough for a package of decent tobacco.

So, you might ask, why should we care that those people or their contemporary avatars have vanished from the city? Isnt it pleasant that Saint-Mdard has been so nicely cleaned up and aired out that now it looks like the parish church in Anyville? And isnt it at least sanitary that Place des Ftes has been so artfully landscaped? And if it is surrounded by monolithic high-rises with all the charm of industrial air-conditioning units, doesnt that at least mean they are designated for low-income housing? Because, after all, if the low houses that ringed the square before urban renewal claimed it had been cleaned and repaired instead of being razed, no one living there could today afford the neighborhood. There are indeed a few places in Paris where the poor can live, but the requirement is that those places be inhuman, soulless, windswept. In the past the poor were left to hustle on their own, which might mean accommodating themselves to squalor, with accompanying vermin; the bargain they are offered today assures them of well-lit, dust-free environs with up-to-date fixtures, but it relieves them of the ability to improvise, to carve out their own spaces, to conduct slap-up business in the public arena if that is what they wish to do. They are corralled and regulated in ways no nineteenth-century social engineer could have imagined.

The flea market called March des Patriarches, Rue Saint-Mdard, circa 1910