Harvey - Paris, Capital of Modernity

Here you can read online Harvey - Paris, Capital of Modernity full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York;NY;Paris, year: 2006, publisher: Routledge, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

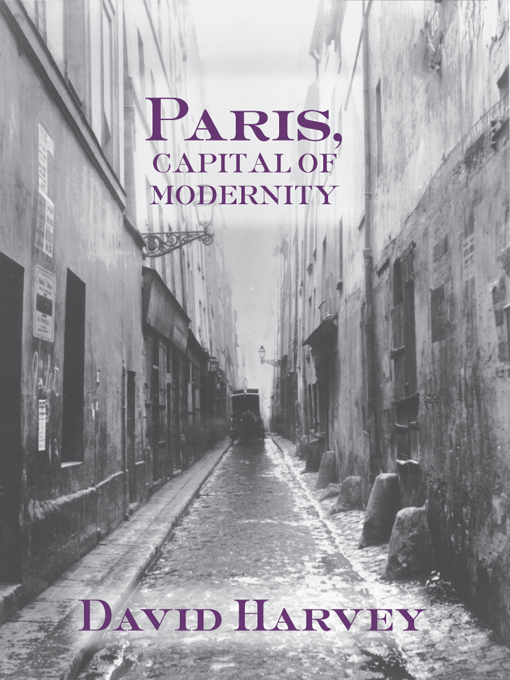

- Book:Paris, Capital of Modernity

- Author:

- Publisher:Routledge

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- City:New York;NY;Paris

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Paris, Capital of Modernity: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Paris, Capital of Modernity" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Paris, Capital of Modernity — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Paris, Capital of Modernity" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Academic Press 35

Amgueddfa ac Orielau Cenedlaethol Cymru/National Museums & Galleries of Wales 54

Artography 6, 14, 17, 26, 42, 51, 83, 92, 94, 116 (bottom)

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2

Beth Lieberman 25, 36

Bibliothque Nationale 13, 15, 21, 24, 27, 37, 40, 59, 63, 70, 71, 76, 77, 85, 95, 98, 99, 101

Collections dAffiches, Alain Gesgon 118

Editions du Seuil 105

Editions de la Couverte 102

The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. 66

Photothque des Muses de la Ville de Paris/Clich Andreani 8, 43, 75A, 78, 79A, 79B, 91A; Bertheir, 9, 75B; Briant, 3, 4, 19, 32B, 33, 38, 46, 86A, 107A; Degraces, 18, 44, 84B, 114, 116; Giet, 89A, 89B; Habouzit, 11, 28A, 82, 84A, 86B, 108A; inconnu, 74A; Joffre, 16, 29, 30, 32A, 91B, 100, 104, 107B, 110, 111, 112, 113, 115; Ladet, 10, 28B, 31, 39, 57, 69, 73A, 81, 87, 103; Lifeman, 88; Pierrain, 5, 7, 52, 60, 65A, 108B; Trocaz, 34A, 72, 73B; Toumazet, 65B, 74B

Runion des Muses Nationaux/Art Resource, NY 1, 22, 23, 67, 90B

Scala/Art Resource, NY 90A

Trustees of the British Museum 12

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore 80

One of the myths of modernity is that it constitutes a radical break with the past. The break is supposedly of such an order as to make it possible to see the world as a tabula rasa, upon which the new can be inscribed without reference to the pastor, if the past gets in the way, through its obliteration. Modernity is, therefore, always about creative destruction, be it of the gentle and democratic, or the revolutionary, traumatic, and authoritarian kind. It is often difficult to decide if the radical break is in the style of doing or representing things in different arenas such as literature and the arts, urban planning and industrial organization, politics, lifestyle, or whatever, or whether shifts in all such arenas cluster in some crucially important places and times from whence the aggregate forces of modernity diffuse outward to engulf the rest of the world. The myth of modernity tends toward the latter interpretation (particularly through its cognate terms of modernization and development) although, when pushed, most of its advocates are usually willing to concede uneven developments that generate quite a bit of confusion in the specifics.

I call this idea of modernity a myth because the notion of a radical break has a certain persuasive and pervasive power in the face of abundant evidence that it does not, and cannot, possibly occur. The alternative theory of modernization (rather than modernity), due initially to Saint-Simon and very much taken to heart by Marx, is that no social order can achieve changes that are not already latent within its existing condition. Strange, is it not, that two thinkers who occupy a prominent place within the pantheon of modernist thought should so explicitly deny the possibility of any radical break at the same time that they insisted upon the importance of revolutionary change? Where opinion does converge, however, is around the centrality of creative destruction. You cannot make an omelet without breaking eggs, the old adage goes, and it is impossible to create new social configurations without in some way superseding or even obliterating the old. So if modernity exists as a meaningful term, it signals some decisive moments of creative destruction.

Ernest Meissoniers painting of the barricade on the Rue de la Mortellerie in June 1848 depicts the death and destruction that stymied a revolutionary movement to reconstruct the body politic of Paris along more utopian socialist lines.

Something very dramatic happened in Europe in general, and in Paris in particular, in 1848. The argument for some radical break in Parisian political economy, life, and culture around that date is, on the surface at least, entirely plausible. Before, there was an urban vision that at best could only tinker with the problems of a medieval urban infrastructure; then came Haussmann, who bludgeoned the city into modernity. Before, there were the classicists, like Ingres and David, and the colorists, like Delacroix; and after, there were Courbets realism and Manets impressionism. Before, there were the Romantic poets and novelists (Lamartine, Hugo, Musset, and George Sand); and after came the taut, sparse, and fine-honed prose and poetry of Flaubert and Baudelaire. Before, there were dispersed manufacturing industries organized along artisanal lines; much of that then gave way to machinery and modern industry. Before, there were small stores along narrow, winding streets or in the arcades; and after came the vast sprawling department stores that spilled out onto the boulevards. Before, there was utopianism and romanticism; and after there was hard-headed managerialism and scientific socialism. Before, water carrier was a major occupation; but by 1870 it had almost disappeared as piped water became available. In all of these respectsand more1848 seemed to be a decisive moment in which much that was new crystallized out of the old.

Daumiers LEmeute (The Riot), from 1848, captures something of the macabre, carnivalesque qualities of the uprising of February 1848. It seems to presage, with grim foreboding, the deathly outcome.

So what, exactly, happened in 1848 in Paris? There was hunger, unemployment, misery, and discontent throughout the land, and much of it converged on Paris as people flooded into the city in search of sustenance. There were republicans and socialists determined to confront the monarchy and at least reform it so that it lived up to its initial democratic promise. If that did not happen, there were always those who thought the time ripe for revolution. That situation had, however, existed for years. The strikes, street demonstrations, and conspiratorial uprisings of the 1840s had been contained and few, judging by their unprepared state, seemed to think it would be different this time.

On February 23, 1848, on the Boulevard des Capucines, a relatively small demonstration at the Foreign Ministry got out of hand and troops fired at the demonstrators, killing fifty or so. What followed was extraordinary. A cart with several bodies of those killed was taken by torchlight around the city. The legendary account, given by Daniel Stern and taken up by Flaubert in Sentimental Education , focuses on the body of a woman (and I say it is legendary because the driver of the cart testified that there was no woman aboard).a boy would periodically illuminate the body of the young woman with his torch; at other moments a man would pick up the body and hold it up to the crowd. This was a potent symbol. Liberty had long been imagined as a woman, and now it seemed she had been shot down. The night that followed was, by several accounts, eerily quiet. Even the marketplaces were so. Come dawn, the tocsins sounded throughout the city. This was the call to revolution. Workers, students, disaffected bourgeois, small property owners came together in the streets. Many in the National Guard joined them, and much of the army soon lost the will to fight.

Daumier hilariously reconstructs the moment when the street urchins of Paris could momentarily occupy the throne of France, while joyously racing around the abandoned Tuileries Palace. The throne was subsequently dragged to the Bastille and burned.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Paris, Capital of Modernity»

Look at similar books to Paris, Capital of Modernity. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Paris, Capital of Modernity and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.