Beloved Delhi

Hum sub ke mehboob shaayar Firaaq sahab marhoom ne apne ek mazmoon mein badi patey ki baat likhi thi, ke agar muarrikh Hindustan ki taareekh ke liye qalam uthaaye, toh usey hamaare classiki adab ka sahaara lena hoga, khusoosan Urdu ghazal ka. Yoon toh Dilli par beshumaar kitaabein likhi gayi hain aur likhi ja rahi hain, magar Saif ki kitaab is lihaaz se judagaana haisiyat rakhti hai ke ye kitaab is ahad ki shayari aur taareekh ka ek khubsoorat imtizaaj hai.

(Our beloved poet, the dear departed Firaq sahib, had once written something very important in one of his essays, that if a writer is to pick his pen to write the history of Hindustan, he will have to take recourse to our classical literature, especially the Urdu ghazal. Many books have been written on Delhi and are being written but Saifs book occupies a distinct position insofar as his book is a beautiful admixture of the poetry of this age and its history.)

Zehra Nigah

Saif Mahmood hamaare maashre ki rooh ko bhi samajhte hain aur Urdu zabaan-o-adab ki qadron ka bhi gehra shaghaf rakhte hain. Is kitaab ki shakl mein unhon ne apne parhne waalon ke liye ek khoobsoorat aur waqee tohfa pesh kiya hai.

(Saif Mahmood understands the temperament of our society and also has a deep passion for the values of Urdu language and literature. In the form of this book, he has offered his readers a beautiful and precious gift.)

Shamim Hanfi

To Naani Ammi, Begum Nayyara Hasan, the most liberal woman in my life ever, every conversation with whom had a flourish of Urdu poetry.

Maqdoor ho toh khaak se poochhoon ke ae laeem

Tu ne vo ganj-haaye gira-maaya kya kiye

If I were given the power, I would ask the Earth, O miser!

What have you done to those precious treasures [that were buried in you]?

Mirza Ghalib

CONTENTS

MIRZA MOHAMMAD RAFI SAUDA

The Great Satirist (17131781)

KHWAJA MIR DARD

Urdus Dancing Dervish (17211785)

MIR TAQI MIR

The Incurable Romancer of Delhi (17221810)

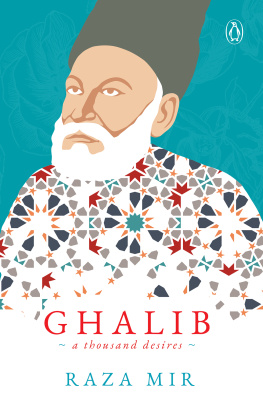

MIRZA ASADULLAH KHAN GHALIB

The Master of Masters (17971869)

MOMIN KHAN MOMIN

The Debonair Hakim of Delhi (18001851)

BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR

An Emperors Affair with Urdu (17751862)

SHAIKH MOHAMMAD IBRAHIM ZAUQ

The Poet Laureate (17881854)

NAWAB MIRZA KHAN DAAGH DEHLVI

The Last Casanova of Delhi (18311905)

Foreword

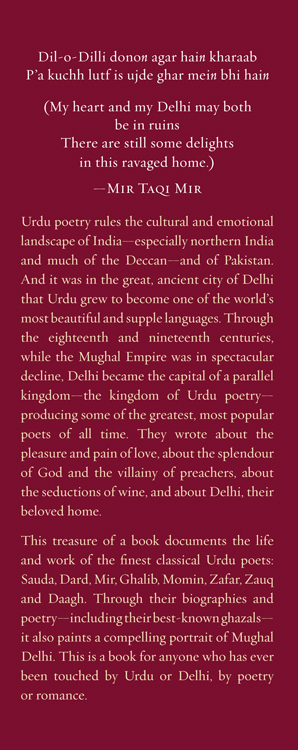

P OLITICS AND POETRY ARE SAID TO BE INTERWOVEN, EVEN IF they arent equivalent. In the Delhi of the nineteenth century, everybodyfrom the king down to the impoverished vagrant singing in the koocha and bazaarwas smitten with poetry. Before 1857, before the long twilight of the Mughals had turned to dark night, poets had dominated the citys cultural and intellectual landscape; they were held in greater esteem than the later emperors, whose rule extended no further than the shabby grandeur of the Qila-e-Moalla, or the Exalted Fort, as the Red Fort was then called. After 1857, the political climate became far too volatile for poets to write of Delhi with the old flair and confidence. They could, at best, defend or decrydepending upon their lot after the cataclysmic events of the Great Revoltthe causes and effects of the annus horribilis that was to change their city and their lives irrevocably. And this they did in prodigious amounts of poetry written in Urdu during and after 1857.

Even prior to 1857, there existed a body of poetry known as shehr-ashob, literally meaning misfortunes of the city, to express political and social decline and turmoil. The first proper shehr-ashob is said to have been written by Mir Jafar Zatalli, one of Urdus most incendiary poets, who is believed to have lived between 1658 and 1713. The shehr-ashob of Zatallis period had elements of satire and humour and flashes of political insight; Zatalli himself was unsparing in his criticism of all authority, including the emperor, for which he was sentenced to death by Farukkhsiyar. But with time the lighter, sharper elements were leached out of shehr-ashob and what was left was highly romanticized, poignant, pathos-laden protest poetry, usually about the city the poet dwelt in. And yet, while this genre of poetry became largely melodramatic, self-pitying and exaggeratedwith a great deal of rhetoric and play upon words in the best traditions of elegiac poetry such as nauha, marsiya and sozit also provided ample opportunities for the poet to paint graphic word pictures of what he saw and experienced at first hand. Twinned with the conventional imagery of the Persian-Arabic tradition, shehr-ashob allowed the poet to bemoan a crumbling social order while speaking, ostensibly, of his personal sorrows and losses. This was what the greatest exponents of shehr-ashob finally managed to achieve: Hatim, Sauda and Mir, each in his own way, pulled Urdu poetry out of the thrall of romanticism andwhile retaining the classical idiom and syntax of the ghazal, masnavi and qasidah formsmade Urdu poetry speak of newer concerns.

Pioneers and innovators like Hatim, Sauda and Mir may have been the best chroniclers of Delhi in verse, but it must be noted that even the most traditional among the poets of Delhi have always had a finger on the pulse of the city. There is something about the fiza and maahaulthe very air and general climateof the city that its poets have never been ghaafilobliviousto the political fault-lines that have marred the tenor of its social and cultural life through the centuries. The great Urdu poets of Delhi always took note of the disarray, mismanagement and decline around them and it is this, coupled with their mastery over the intricacies of the ghazal, that makes their poetry so distinctive. Rooted in the topical and the contemporary it might be, it continues to speak to us across time and circumstance.

Poetry, it has been said, flourishes when all else withers. When there is political chaos, when the social fabric tears, when corruption and poverty become rampant, whenin the words of that other great poet, Yeatsthe centre does not hold, it is usually the poets finest hour. And so it was in the last years of Mughal rule in India. From the middle of the eighteenth century, events conspired to give plenty of fodder to the Urdu elegists mill. There was the decline and dismantling of the Mughal empire with each successive incompetent ruler. There was the sack of Delhi by Nadir Shah; the series of invasions of the city by Ahmad Shah Abdali and plundering raids by the Marathas and the Rohillas; the establishment of British control over Delhi in 1803; and the most cruel blow of allthe annexation of Awadh in 1856which turned even loyal Muslim supporters of the British in Delhi and elsewhere into discontented, suspicious malcontents, if not ardent jehadis. With each fresh catastrophe, the Urdu poet evolved a vocabulary to express his angst, clothing his sorrow in a time-honoured repertoire of images and metaphors. Some favourite synonyms for the Belovedsitamgar, but, kaafir, yaarnow began to be used mockingly for the British. And so it went ontwo worlds colliding, or waiting to merge and fuseone dying and the other waiting to be born!

The book you hold in your hands encapsulates this twilit, churning world: it not only documents the life and often turbulent times of some of the finest poets the city of Delhi has produced, but also gives you a sample of their most representative work in English translation. The photographs accompanying the text do an admirable job of connecting the modern reader almost immediately with a past that lingers in the by-lanes of Purani Dilli and catches us unawares every now and then.