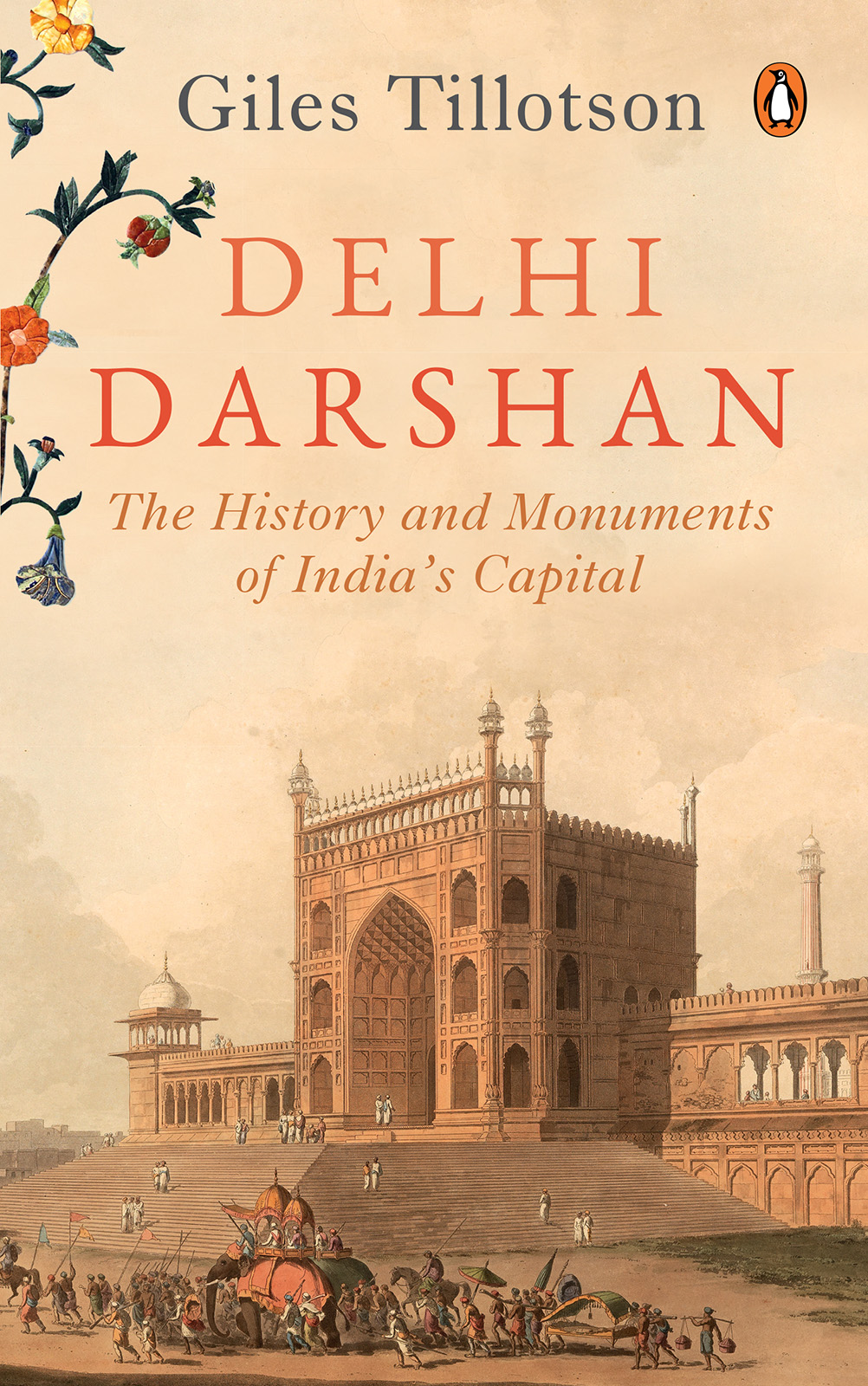

Introduction

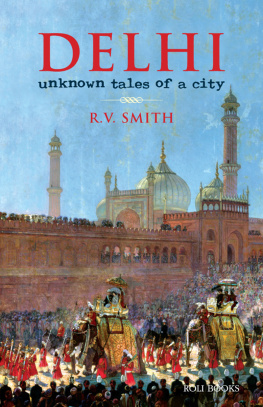

I ts origin and antiquity may be disputed, but Delhi has without doubt been a major cityeven a capital city, on and offfor at least a thousand years. It has served as a centre of power for Rajput clans, for the first sultans, for Mughal emperors, for the administrators of the British Raj in the early twentieth century, and for Indias federal government since Independence in 1947. Successive regimes established themselves on adjacent or overlapping sites, adding to Delhis vertical layers and its horizontal spread. Old guidebooks speak of the seven cities of Delhi; but these were all Islamic citadels, built before the coming of the British, and in recent times archaeologists have added more cities to the bottom of the tally just as developers have added many more to its top.

The Mughals built their walled city in the seventeenth century by the riverbank, as far away as topography would permit from the earliest settlements. Three centuries later the British added their geometrically planned extravagance in the mostly empty centre, between the Mughal city in the north and the ruined sultanate forts in the south. In the late twentieth century, new housing colonies filled up all the spaces in between, and in the new millennium the spread has extended beyond those historic boundary markers, both south-westwards into the farmlands of the hinterland and eastwards across the Yamuna river, to create the new satellite cities of Gurgaon and Noida. The aggregateofficially called the National Capital Regionis today among the largest and fastest-growing urban conurbations in the world.

Neither history nor geography, however, fully conveys the citys characteristic layering: the constant interaction between its present and its past. The past informs the present in obvious ways, as we live amid historic sites; but the present also informs the past in the sense that we encounter old sites in our own time, through the lens of recent use. This book, intended as an introduction for anyone who lives in or visits the city, explores its sites not only in relation to their own time, but in terms of what subsequent periods have made of them, examining some of their accumulated meanings and myths.

To residents of Delhi, for example, the famous India Gate is not just a war memorial; for a long time it has also been a favoured place to go for an ice cream on a hot summer night, and lately it has become a place where members of civil society collect to protest miscarriages of justice. Political protesters traditionally prefer to congregate at Jantar Mantar, an eighteenth-century observatory, despite periodic attempts by the authorities to prohibit its use for politics. The Lodi Gardens is not just the location of some early tombs but a place for picnicking, jogging and falling in love; it is one of the few spaces where public displays of affection are tolerated, perhaps because the relative affluence of the average Lodi Gardens visitor deters officious intervention. The Red Fort, built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, now serves as the podium for an annual speech to the nation by the prime minister on Independence Day. Such later uses are as important as the original functions in explaining how the buildings are seen today.

The Purana Qila, or old fort, marks a point of origin or new beginning in various time zones. Built in the sixteenth century, it is by no means the oldest fort in Delhi, despite its name: it is called purana because it predates the walled city of Shah Jahan and was the Mughals first establishment in Delhi. It is also popularly believed to mark the site of Indraprasthathe capital of the Pandavas, the heroes of the Mahabharatataking the history of the city into Indias epic past. Modern excavations have indeed revealed very early pottery remains, confirming that identification for those who are willing to believe in it. But the archaeologists could move into the site only after the departure of the refugees: at the time of Independence and Partition in 1947, and for some years afterwards, the enclosed sanctuary of the Purana Qila was used as a transit camp by many who were escaping communal violence in the old city or preparing to migrate to Pakistan; and later some of those who had fled from it. Those who came from the western part of Punjab form a significant core of Delhis senior generation, and for some of them the old fort was the site of their new beginning, in a new nation.

Such layering is everywhere. Humayuns tomb is not only the burial place of one of the early Mughal emperors, it is also the place where his last ruling descendant, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was arrested, at the bloody denouement of the 1857 uprisings. Driving around the elegant avenues of New Delhi, lined by government servants bungalows protected by high fences and armed guards, you might at first take the scene as typical of Indian officialdom: such apparent self-importance! But look again and you realize that nothing has changed since the 1930s; that this is a colonial city after all, modelled in part on a military cantonment. On the other hand, few people today would regard Rashtrapati Bhavan (the former Viceroys House) or the Secretariats as legacies of colonial rule: they may be massive and imperial, but they are more popularly associated with independent Indias successive presidents and ministers. They are proud symbols not of the past but of the present.

Just as the past erupts into the present, so the present refashions the past according to its own compulsions. This is what makes Delhi so intriguing and makes spending time in it worthwhile. Highly congested and with poor infrastructure, Delhi is a difficult city to live or move around in, but its shortcomings fade if we have an eye for its many layers. The chapters of this book together present a concise history of the city, focusing on its most prominent people and places. A brief concluding section describes some suggested routes for exploring the city. I have avoided cluttering the text with the scholarly apparatus of notes and references. Readers who are curious about my sources for particular pieces of information and quotations, or just want to know more, can look up the section titled Further Reading.

Having thus conveyed an impression of a wish to be at once brief, authoritative and helpful, I should add that this short book is very much a personal view of Delhi which reflects my own prejudices and preoccupations. Much has been written about the city, especially in recent years, by a number of writers with a range of approaches and specialist expertise. I point to some of this in Further Reading. I have learnt from and draw from this writing; but I have made no attempt to be comprehensive or encyclopaedic. I am an architectural historian, with a range of interests in Rajput, sultanate, Mughal, colonial and modern architecture. I look at design, but I also look at how any building is rooted in history, often in more than one period. So if you share my interests in history, architecture and designand whether you know Delhi less well, as well, or better than I doI hope that you will find something of pleasure and profit in reading my take on it.