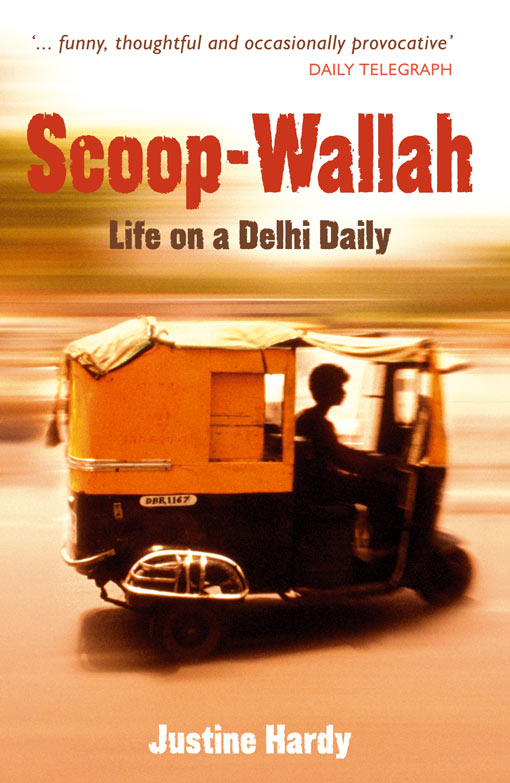

SCOOP-WALLAH

Life on a Delhi Daily

Justine Hardy

SCOOP-WALLAH

This edition published in 2009 by Summersdale Publishers Ltd.

First published by John Murray (Publishers) Ltd in 1999.

Copyright Justine Hardy 1999

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

The right of Justine Hardy to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-0-85765-968-2

The author and publishers would like to thank A. P. Watt Ltd on behalf of The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty for permission to reproduce extracts from the Kipling Papers; Rudyard Kipling, Something of Myself.

Also by Justine Hardy:

The Ochre Border: A Journey through the Tibetan Frontierlands

Goat: A Story of Kashmir and Notting Hill

Bollywood Boy

The Wonder House

In the Valley of Mist: One Kashmiri Family in a Changing World

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justine Hardy has spent much of the past eighteen years writing and reporting from India for papers ranging from The Indian Express, the subject of this book, to the Financial Times. Since Scoop-Wallah was first published ten years ago there have been several other books including, Goat, A Story of Kashmir and Notting Hill, Bollywood Boy, a best-selling dig into the Hindi film industry, and The Wonder House, a novel set against the long conflict in Kashmir. Scoop-Wallah was short-listed for the Thomas Cook Award when it was first published, and serialised on Radio 4. Justine continues to divide her time between England and India.

For Gautam

and another side of India

as it tries to find

its voice

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is about people. It relies on them for its flesh and blood. The risk I take in putting them down on paper is that no one likes to see themselves in black and white. If you say they are beautiful they will say you are a liar. If you say they are ugly they will sue. You can't win, so you just have to cross your fingers.

In India I was welcomed in so many places. Thank you, Sourish and the gang at The Indian Express; Rani Sahiba and Maharaj Sahib at Hailey Road; Vijai and Rani Lal in Delhi and Pragpur; Billy and Alka Singh in Assam; Mr and Mrs Krishna at Jangpura Extension; and Reggie Singh in Simla. My love to Paddy and the boys in the office, Tarun, Dev, Manoher, Yaatendra and Sashi, to Gita for your enthusiasm and to Rajiv, my lifeline. Thank you, Arvind, for the polo views, and the Delhi Polo Club for the horses and afternoons of sanity. Readers interested in DRAG can write to: DRAG, 75 Paschimi Marg, Vasant Vihar, New Delhi 110057 (tel: 00 91 112 614 2383).

In England there is one person who started all this Peter Hopkirk because he said that I could not possibly work on an Indian newspaper and not write about it. My gratitude to Gail Pirkis at John Murray for rebuilding me. Such appreciation to Alastair Williams, Jennifer Barclay and everyone at Summersdale for picking this book up out of the dust again. A big thank you to Will Curtis for his pictures of Assam and Spiti.

My greatest debt, however, is to two people my mother and Raj Kumar Yashwant Singh, the Prince of Hailey Road. Carry on regardless.

INTRODUCTION

Finding an old photograph again, shoved between the pages of book, or pushed into the back of a wallet or diary, triggers whirling landscapes of memory. I mean those ones from a time of seismic change in our lives, marking a point when everything shifted, either in our own world, or in the wider one. How many of us tried to get hold of a small grey lump of the Berlin Wall after 9 November 1989, or have looked for a photograph taken sometime just before 11 September 2001, a reminder of how we felt just before the world seemed to lurch? We peer at our expressions in the picture, looking for some sign that perhaps we had a sense then that everything was about to change.

This book is a photograph of sorts, a verbal image that captures a country and a capital as both began to go through a vast transformation: in short, as India began to shift from poor relation to rock star status.

Scoop-Wallah was first published exactly ten years ago and, though it is getting harder to imagine, India's capital was not the venture capitalist magnet that it is now. Today's business visitors shake their heads at the juxtaposition of a Porsche Cayenne next to a bicycle rickshaw at a jammed city traffic light, the tourist contrast, a photogenic one that takes a snappy picture, summing up rising India. Ten years ago an imported car was almost as rare on the streets as a public loo, something very hard to find and fairly tough on the resolve, if and when you did track one down, usually by sense of smell.

When I was writing this book, Delhi was still considered a hardship posting by the majority of foreign companies and diplomatic delegations based there. I remember a couple at a lush cocktail party at the American Embassy in 1997. They were coming to the end of their three-year posting. The wife had not left the compound once during that time. She was terrified of being kidnapped or catching some airborne disease. She smiled nervously when someone else in the conversation suggested that she was breathing the same air, inside the compound, as the rest of Delhi was breathing beyond the high razor-wire topped walls. She said that she did not go out of the air-conditioning often and seemed confused by our surprise. Now families from that same embassy, ones that once made a habit of flying home to the US for holidays, take to Kashmir for extreme skiing during the Christmas break, a conflict zone still considered unsafe according to most foreign office travel advisory services.

India is more confident, and those coming to live and work there are too.

In those ten years Delhi has moved from hardship posting to highly shined world player with an economy driven partly by its own success, though it has also been heavily invested in by a US government and business sector, both keen to promote India as the buffer zone between totalitarian China and the democratic world beyond, from the High Himalayas to the New England Coast.

India both demands a sense of humour, and is one. Much of its survival amidst apparent chaos and regional anarchy is perhaps due to the cultural shrug summed up in the Hindi expression jo hona hai hoga, which pretty much translates into the perky made-up language line: Que Sera Sera. There is a Doris Day cheeriness to it, a smiley acceptance of everything, from the deeply sublime to the utterly ridiculous. Outsiders, or more exactly those looking for insto-enlightenment on the Magical Mystery tour, see this acceptance as a part of karma, the unalterable cycle of cause and effect. They try to imbibe it, package it up, and unpack it back home at their nearest yoga centre on their eco-friendly mat. But for those living within the grinding extremes it is more about the unwieldy volume of humanity, and the equally heavy weight of corruption, a combination that keeps most people confined to the particular groove or rut into which they were born.