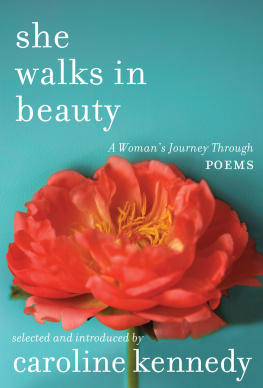

Sideways on a Scooter is a work of nonfiction.

Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright 2011 by Miranda Kennedy

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to The Random House Group Ltd., London, for permission to reprint an excerpt from Birches by Robert Frost, from The Poetry of Robert Frost, edited by Edward Connery Lathem, published by Jonathan Cape. Reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd., London.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Kennedy, Miranda.

Sideways on a scooter : life and love in India / Miranda Kennedy.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60455-6

1. WomenIndiaDelhiSocial life and customs. 2. WomenIndiaDelhi

Social conditions. 3. WomenIndiaDelhiBiography. 4. Man-woman

relationshipsIndiaDelhi. 5. LoveSocial aspectsIndiaDelhi.

6. Kennedy, MirandaTravelIndiaDelhi. 7. Delhi (India)Description

and travel. 8. Delhi (India)Social life and customs. 9. Delhi (India)

Social conditions. 10. Social changeIndiaDelhi. I. Title.

HQ1745.D4K46 2011

305.4095456dc22 2010020297

www.atrandom.com

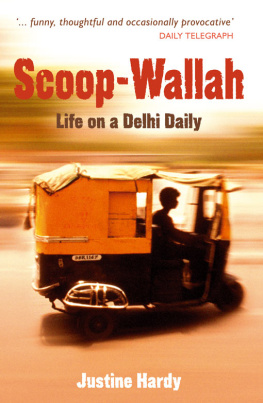

Jacket design: Daniel Rembert

Jacket photograph: Hugh Sitton/Corbis

v3.1

For my father,

who taught me

the love of reading,

and for Annie,

who illuminates

Contents

CHAPTER 1

Are You Alone?

D elhis stale April air caught in my throat. Each breath had already been recycled through millions of Indian mouths, I imagined, growing hotter and thicker with each exhale. This is what it must feel like inside a burka: It was as though I was enclosed from head to toe in black cotton and inhaling the fabric that covered my mouth as I tried to scoop the dusty soup into my lungs.

Natural air-conditionings, madam! Full breezeopen like a helicopter!

When a three-wheeled auto-rickshaw slowed to a sputter alongside me, I was uncomfortable enough to pay attention to the drivers offer. Id only been in India for a couple of weeks, but Id already learned that most of Delhis rickshaw drivers choose to nap away as much of the seven-month hot season as they can, sprawled across their backseats in a pool of sweat. When the temperature sails above a hundred degrees, they hike their fares to ensure that the predatory customers leave them to nap in peace. This driver must have been especially hard up. He gave me an exaggerated salesmans smile, disturbing the too-small pair of plastic glasses jammed onto his face, and agreed to a reasonable fare without arguing. I scrambled in, immediately grateful for the relief his rickshaws flimsy canvas top provided from the sun, and for the slight breeze of his helicopter with two open sides.

The peppery smell of areca nut stung my nostrils as my driver dug a leaf-wrapped packet of paan out of a metal box and pulled it open with his teeth. Paan, a strong stimulant like chewing tobacco, reddens the teeth and lips of laborers, delivery boys, and shopkeepers across India. When my mother had first come to South Asia, shed assumed the men were all dying of tuberculosis, spitting blood onto the streets. She had been only twenty-threeyounger and even more nave than I was when I first arrived, at twenty-seven. In fact, paan is a relatively innocuous vice, the working mans way of getting through the day, as one friend later described it. If the middle class relies on air-conditioning and chauffeur-driven cars to endure the disorder and discomfort of Indian city life, everyone else blunts its frustrations with cheaper and more accessible aids, such as paan, hand-rolled cigarettes called bidis, and Bollywood films.

The rickshaw spluttered through Paharganj, a seedy district for low-budget tourists where British accents jostle with the guava sellers Hindi cries and the shouts of the aggressive red-shirted porters at the railway station nearby. Adjacent to New Delhi Station, this area is the landing point for Israelis letting off steam after their mandatory military service, and for lost European souls in search of Afghan heroin or Russian prostitutes, or both. Its a little ironic that it is also where those in search of spiritual awakening come to lay their yoga mats. Paharganj isnt the real India, but it was the version my parents would have seen when they made their way along the hippie trail to India back in the seventies. This, the spiritualized, photogenic India sought out by Western wanderers, didnt really parse with the globalizing India that Id read about, of cable TV and McDonalds McAloo Tikkis.

Although I have been known to do yoga, I wasnt especially interested in a New Age-y ashram experience of India. However, there was no getting around the fact that Id shown up in Delhi dressed the part. It took me longer than it probably should have to realize that outfits such as a long, wrinkled beaded skirt and tight black cotton eyelet top werent doing me any favors in India, where neatness is sometimes the only way to tell the slightly poor from the desperately impoverished. Compared to Delhis ladiesimpeccable in freshly ironed silk saris and tiny beaded slippers, and radiating a fragrance of baby powder and palm oilI looked like a sloppy hippie.

A few hours earlier, in the breakfast room of the Lords Hotel, I had looked down at the strips of papaya and clumpy yogurt in front of me and tried to concentrate on my goals for the day. Half watching the translucent geckos skitter across the walls, I reviewed the list of interviews I wanted to set up, the apartment search I needed to embark on. It seemed overambitious and strangely irrelevant when I considered my surroundings: a cheap druggy travelers hotel in a chaotic city that would seethe its way through the day no matter what I did with mine. I sighed in frustration and turned my attention to the geckos. Through their bodies I could see the cheery red and pink frescoes of Hindu gods.

I was determined to be more than a casual visitor to India. Id been saving everything I earned at my job as a producer at a public radio show so that I could pick up and go overseas to try my hand at becoming a freelance foreign correspondent. The lack of transcendent, transformative experiences in my life so far had disappointed me: My days seemed a blur of headlines and deadlines. And even though it was a nineteenth-century idea, I couldnt help but worry that I needed to make a dramatic gesture to convince my New York boyfriend to stick it out with me. As much as I wished I could stride into the world without caring about such things, it wasnt that simple. I hoped that by taking myself off to the farthest, most exotic place I could imagine, Id make myself more appealing to him.

There was never any question in my mind that India was where Id go to do it. My familys fascination with the place dates back to 1930, when my British great-aunt Edith traveled there as a Christian missionary. My mothers side of the family is a small, close-knit group of wanderers, and Id always expected that I would be like the rest of them. Going to India was like a rite of passage, entwined with my very idea of myself. Although the decision didnt make much sense to my friends, I had an idea that I would become my fullest, most interesting self there.