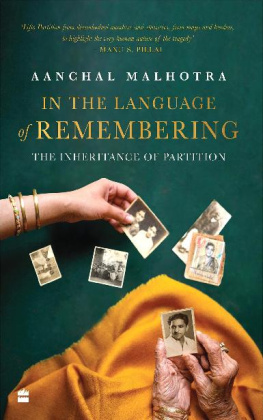

T AKING THE METAPHOR OF a banyan tree, whose roots hang in the air, Nina, one of Aanchals interviewees, tells her that when there is no land for the roots to grow out of you are the outcome of a fractured history. It is this fractured history of the subcontinent felt, embodied and inherited, owned and disowned, across geographies and generations that Aanchal attempts to map in In the Language of Remembering.

In her first book, Remnants of a Separation , Aanchal compellingly showed us the ways in which the material memory of Partition is carried across borders; in a powerful sequel to her debut book, she emphasizes that this memory, material or otherwise, is not confined to Partition survivors. The memory is passed on, shaping and reshaping the ways in which Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis continue to understand their past and give meaning to their present. In doing so, Aanchal builds on the work of scholars who have long indicated that Partition is far from a frozen event, or an event of the past. Partition remains ongoing.

A decade earlier, as I began speaking with Indians and Pakistanis for my book The Footprints of Partition , exploring the journey of Partition after Partition, studying the ways in which the memory of 1947 had transformed over generations, it was this ongoing facet of Partition that emerged in countless conversations. Whether in India or Pakistan, or later in Kashmir and Bangladesh, the ways in which people related to Partition, spoke of it, remembered it, silenced or cast it away signified that 1947 was not a static event.

Sometimes I came across third generations, as Aanchal does, who became intrigued in researching Partition because of the silencing they had experienced growing up. Their parents, their grandparents never spoke of it, never wanted to delve into it, pushing the younger generations to find their own meaning of home, loss, belonging. Others had family members across lines of division, and continued to be deeply impacted by visa restrictions, bureaucratic hurdles, Indo-Pak hostilities and warmongering. Some conversations symbolized how post-Partition events had left deep imprints on peoples understanding of 1947, informing the ways in which they saw themselves and the other whether Muslim, Hindu or Sikh within our countries, or Indians and Pakistanis across the border.

While some post-Partition events, such as the birth of Bangladesh in 1971, have overshadowed the events of 1947 in the collective and national imaginations, through her conversations, Aanchal shows that in other cases, such as the anti-Sikh pogrom of 1984, the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, or the more recent Citizenship Amendment Act in India, Partition itself becomes a reference. It has the potential to evoke a re-experiencing: of fear, of uncertainty, of anxieties experienced by communities in 1947. And for some families, it was this post-Partition violence that made Partition ever more relevant, immediate and palpable even decades after Partition.

By conducting interviews across generations, and collecting stories spanning the vast geography from Afghanistan to Burma, Kashmir to Karnataka, Aanchal is able to indicate the moments at which Partition, and the memory thereof, emerges and re-emerges. But these are not political or macro moments alone. Rather, her conversations powerfully also depict the presence of Partition in our everyday. Partition and the pre-Partition are evoked not just in political rhetoric by nation-states or during periods of war and violence but also in the most mundane moments within families: in a whiff of recipe carried over, a word spoken here or there, an accent or dialect, a name of a street or neighbourhood representing the pre-Partition past of its residents, a tradition sustained, or the piercing silences, the memories pushed aside, the practices abandoned. The presence and absence, the remembering and forgetting, linger on, each in its own way a response to Partition and its impacts seventy-five years on.

Aanchal begins her interviews by asking her respondents not only when they first heard about their familys stories of Partition but also how old they were and what meaning they gave to those initial fragments of information. In doing so, she creates a canvas of what she calls second-hand memories, showing us the connections and disconnections, the continuity and rupture, and the intricate ways in which Partition emerges and re-emerges across families, communities and generations. As one of her respondents powerfully summarizes:

In a single second, Partition can transform from an event in history to a feeling in the present day. In a single bite, you can be transported to a land youve never seen but your family belongs to. When the food we are eating, the language we are speaking are all remnants of this division, it feels like Partition is woven into our everyday life, and it may remain that way, no matter how many generations come after us.

Given the breadth of interviews in this book, the thoughtful way in which the narratives have been stitched together itself symbolizes the felt-sense, the visceral and the embodied experiences embedded in relation to Partition, making the chapters deeply engaging. Though Aanchal speaks to people across age groups, ethnicities, nationalities and religions, the narratives are gently woven together in a way that cuts across these lines. Titled as Love, Loss, Pain, Regret, Fear and so on, it is emotions that guide these chapters. In thematizing the narratives this way, Aanchal is able to bring together varied experiences across borders and convincingly show us how, regardless of where one might be placed, whether in terms of geography or religion, human emotions triggered by Partition and its memory are shared.

There are recurring themes such as relationships to ancestral lands or the desire to travel across that are common across interviewees. And yet, Aanchal is also acutely aware of the dangers of homogenizing the stories. And so, within each chapter, within each emotion, she creates space for the nuances and uniqueness of each persons story, their memory, their relationship to Partition, reminding us that no matter how much is written about Partition, there is always still so much more to be unearthed.

As a parting note, it remains significant to me that Partition remains so significant to Aanchal. There is an urgency, a quest, a desire to document, to preserve, to archive the memory of Partition. It is an urgency I share; it is an urgency many other South Asians share. The numbers of projects, archives, museums and literary works on Partition that have come to the fore over the last two decades are a testament to this. As a third-generation Indian, and as a third-generation Pakistani, we recognize that time is not on our side. The nuanced stories and experiences of Partition survivors offer an essential lens into our past and present. It is a lens that, for me, provides the only hope to move beyond distorted, jingoistic and censored state histories. But we remain on the brink of losing those who lived through Partition. Countless stories will go unarchived, undocumented. By turning the lens on generational history, we can, however, begin to understand how that memory may be memorialized in other ways, taking on new meanings across families, across borders. In doing so, we can begin to scratch the surface of the long legacy of Partition. The stories and emotions that Aanchal has given a home to are a great service in this direction.