A CLINICAL TERM USED FOR WHEN MANIC-DEPRESSIVE DISORDER FIRST APPEARS EARLY IN LIFE. FOR A LONG TIME, DOCTORS BELIEVED CHILDREN COULDNT SUFFER FROM THE MOOD SWINGS OF THE ILLNESS. DUMB-ASSES.

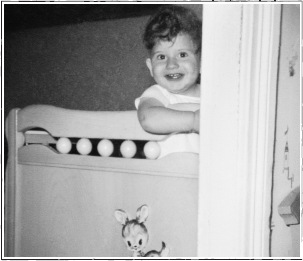

I t was one of the first jokes I learned. My hunch is I picked it up from my wiseass cousin, Barry, when I was about five. Id walk up to people while they were having dinner around our green Formica kitchen table, the one flecked with glitter, and demand, Ask me where I live. Theyd glance at my parents, then, curious, bend over and oblige.

And where do you live, David?

Id lift my left arm like a bodybuilderbicep flexed, fist curledin the shape of Cape Cod.

Here, Id say, pointing to my armpit. Yelps of laughter followed from those who hadnt heard it before. Oh, that kid of yours, Ellie, theyd say to my mother. Shed just flash her what-can-I-say smile and pass bowls of Portuguese rice and platters of fat links of chourio, garlicky pork sausage, with an enormous fork jabbed menacingly into them. With the show over, Id wriggle back onto my seat or open the door and scream for Paneen, my godfather, to come upstairs and carry me to their apartment so I could watch TV with Barry.

If you looked at a map, my hometown of Fall River, Massachusetts, was pretty much in the geographic armpit of the state. Mount Hope Bay divided the South Coast: To the east, Fall River and the tougher city of New Bedford, both swollen with newly arrived Portuguese immigrants; to the west, the more bucolic towns of Somerset and Swansea. And beyond: rarefied Newport, Rhode Island, with its mansions, yachts, and Kennedy history. At the time, I found the joke hilarious, because anything with butt cracks and burps and armpits was funny. It would be a few more years before it took on a different meaning.

I grew up in a sliver of the city called Mechanicsville, which was so inconsequential it was swallowed up by the sprawling and far more regal-sounding North End. On our block of Brownell Street, we kids were indistinguishable. We could end up at each others houses for supper, and our mothers would look at us for a second, confusion creasing their foreheads, and set more plates, as if theyd suddenly forgotten how many children they had. Our parents were just as interchangeable. Act up in someone elses yard, and you could be sure some father would crack you across the ass and think nothing of it. But if a kid from another block began whaling on one of us, all our mothers would fly from their porches, haul off the intruder, and shout down his mother until she and her kid slunk away. It was understood: We were children of the neighborhood. And playing in our slice of the city, which bled into the rocky Taunton River, we didnt know people spat out words like Portagee and greenhorn as a way of insulting our parents and making them feel small. Hell, we didnt even know there was anything other than Portuguese, which meant we didnt know how to be ashamed.

Television showed us that.

I dont remember a time without TV. I was allowed to watch pretty much nonstop while my mother cooked, made beds, rearranged closets, hung laundry, and babysat my cousin Barry and me. But at some point, I noticed there were no families on TV speaking the soft sandpaper shushing of Portuguese words. Houses werent crammed with eight or ten people. No kid was ever forced to eat salt cod or octopus stew that seemed to take on pulsating purple life in the bowl. Fathers werent carpenters, and mothers certainly werent fat. TV people had maids who were plump, but it was always the mothers who pirouetted out of swinging kitchen doors, their dresses fanning open like morning glories, carrying anything made with Velveeta. We didnt even have a door to our kitchen.

What we did have was whole apartments filled with the aroma of pungent garlic and sweet onions slowly melting in big pans. Refogadomy maternal grandmother, Vovo Costa, would tell me its name, urging me to repeat it. Refogado. Meat so smoky I could hold my fingers to my nose hours later and still smell it. My mothers singing, soft and trilling, as she swayed to the radio while cooking in our narrow kitchen. And after dinner, all eight of us draped over the furniture in my godparents parlor. On the wall, watery flickers of Abbott and Costello running from Frankenstein, as my grandfather, Vu Costa, hauled out his wheezing projector and played his favorite movie for us, yet again.

The closest thing to my family I ever saw on TV was The Honeymooners, because my father had been a bus driver back in the Old Country, where he met my mother while she was on vacation from Fall River, where she was born. He never screamed at her like Ralph Kramden or threatened to send her to the moon. But we did have a family friend, Pesky, who wore T-shirts and vests just like Ed Norton.