Copyright 2014 by Charles Phan

Photographs copyright 2014 by Ed Anderson

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Phan, Charles.

The slanted door / Charles Phan ; preface by Patricia Unterma.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60774-054-4 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-60774-580-8 (ebook) 1. Cooking, Vietnamese. I. Title.

TX724.5.V5P539 2014

641.59597dc23

2014015943

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-60774-054-4

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60774-580-8

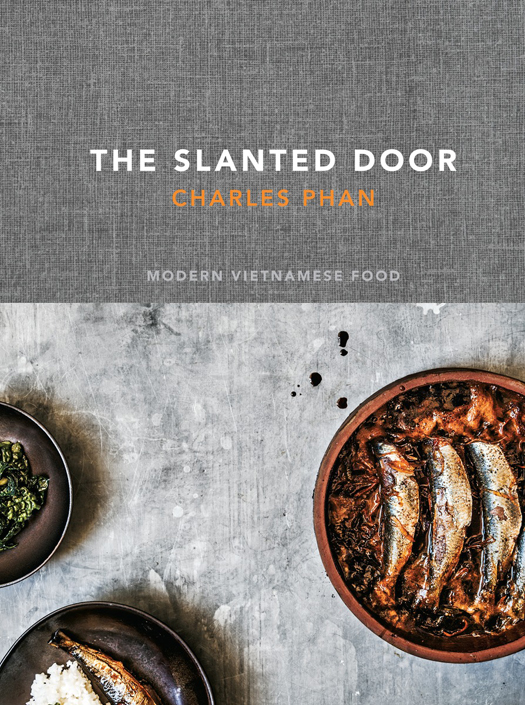

Cover Design by Emma Campion

Prop styling by Ethel Brennan

Photos on by Olle Lundberg and Art Gray.

Photo on by Wain Owings.

Photo on by David Battenfield.

v3.1

TO MY PARENTS, AND TO ANGKANAS;

THANK YOU FOR MAKING ALL OF THIS POSSIBLE

CONTENTS

Act One

584 Valencia Street

1995-2002

Act Two

100 Brannan Street

2002-2004

Act Three

1 Ferry Building

2004-Present

LIST OF RECIPES

FOREWORD BY PATRICIA UNTERMAN

On my first visit to the Slanted Door seventeen years ago, then on a fairly scruffy block of Valencia Street in the Mission, I fell hard for the Charles Phan experience. I had slurped noodles at hole-in-the-wall pho joints and wolfed down the best sandwiches in the world at banh mi shops in the Tenderloin.

I had driven to excellent, if utilitarian, Vietnamese restaurants with extensive menus in Newark and San Jose, where some of the largest Vietnamese communities in the Bay Area live. But the Slanted Door was something else: a Vietnamese restaurant that integrated what was happening on the culinary and cultural fronts in San Francisco, and raised the bar.

The Slanted Doors converted storefront dining room felt both smart and hand built, with colorfully painted wooden tables, tony chairs with wicker seats, contemporary art on the walls, beautiful flowers, and an open kitchen. The tables upstairs in the quieter mezzanine, covered with white linen and butcher paper, hinted at luxe. Phan, a ceramicist and student of architecture, drew on a community of artists and artisans he knew to build and outfit the place, but he did a lot of it himself. He was driven by a vision and a small budget, so he worked on every detail, not the least of which was simple Asian ceramics that somehow made every dish seem new and exciting.

His cooking was vibrant, his food more alive than any Id eaten in other Vietnamese restaurants. Phan committed his kitchen to using fresh, carefully chosen ingredients. He had never cooked professionally, and, just as a dedicated home cook would, he made everything from scratch. In 1995, when the Slanted Door opened, Hmong and Vietnamese farmers were just starting to grow vegetables and herbs for both homes and Asian restaurants, selling them at farmers markets where Phan shopped. He was also seduced by Western vegetables, which he prepared in breakthrough ways with Vietnamese herbs: Brentwood corn with sesame seeds; haricots verts with roasted chiles; old-fashioned Western broccoli with chiles, tofu, and lions mane mushrooms.

In keeping with his hunger for excellent ingredients, Phan began seeking out chicken, pork, and beef raised on small farms to use in his traditional preparations. His sister, Kim Phan, used seasonal fruits in desserts that reflect the French influence on Vietnamese cooking: blackberry napoleons, French chocolate cake la Zuni Caf, and crme caramel.

At the Slanted Door, wine became part of the Vietnamese dining experience. Phans love of fine teas meant that they, too, got nuanced treatment. Presented loose-leaf in a warmed pot with tiny cups and a sand timer, the tea demanded the customers attention. Like the wine list, the tea list described the provenance and character of each tea. Many cost more than wine, unheard of in any other restaurant at the time.

Word of this sophisticated San Franciscostyle Vietnamese restaurant spread like wildfire throughout Bay Area food circles. Lines started forming outside the door at 5 p.m. and didnt let up until closing. With almost a hundred seatshow could there have been that many?the place grossed almost $4 million in its first year, despite its relatively low prices. Every food-crazed San Franciscan and restaurant-savvy tourist wanted to and could afford to eat there.

The charmed Mission location could have continued forever if a disgruntled customer, upset because the Slanted Door wouldnt take reservations, had not complained to the city about the restaurants oversized mezzanine. And so, after seven years, Phan moved the restaurant to bring the Valencia space up to code, setting in motion a series of events that would ensure his legacy as a San Francisco visionary.

Phan found a temporary location on the Embarcadero at Brannan, a former restaurant that left behind a wood-burning oven, a mesquite grill, and a comparatively huge open kitchen. He started throwing vegetables in the oven, dressing them with rau ram and crispy shallots, and wood-roasting clams and whole fish. It was there that he organized his first bar, provisioned with the same eye to quality as his pantry. He stocked small-batch Pappy Van Winkle bourbon in the barrel as well booze!

The temporary Slanted Door thrived in its big new location and Phan wanted to stay, especially since repairs hadnt been completed at the Valencia location. But, as usual, things fell through. He turned to the developers of the Ferry Building, who had been wooing him. Phan picked up the phone, specified his terms and conditions, and hung up. The developers were smart enough to accept on the spot. Then, of course, Phan had to raise money for the build-out fast. His friends and customers came through, lending on the basis of his signature alone. He built the new restaurant in a record ten months.

The current location of the Slanted Door opened in 2004 in a cavernous, echoing, empty Ferry Building. Developers Chris and Michele Meany had also convinced the Ferry Plaza Farmers Market to move its Saturday market from a parking lot a few blocks up the Embarcadero to the Ferry Building. Not a few predicted that these two San Francisco institutions might be doomed by the move. But the opposite happened. The credibility of the farmers market validated the indoor market hall that would eventually open there, and the Slanted Door would draw thousands of diners to the building. And now Phan only had to walk a few yards to shop.