Ethnic Conflict and Protest in Tibet and Xinjiang

Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University were inaugurated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and contemporary East Asia.

For a list of titles in this series, see

Ethnic Conflict and Protest in Tibet and Xinjiang

Unrest in Chinas West

Edited by Ben Hillman and Gray Tuttle

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hillman, Ben. | Tuttle, Gray.

Title: Ethnic conflict and protest in Tibet and Xinjiang: Unrest in Chinas West / edited by Ben Hillman and Gray Tuttle.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015024326 | ISBN 9780231 169981 (cloth : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780231540445 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Tibet Autonomous Region (China)Ethnic relations. | Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu (China)Ethnic relations. | Ethnic conflictChinaTibet Autonomous Region. | Ethnic conflictChinaXinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu. | BorderlandsChina. | ChinaEthnic relations. | Ethnic conflictChina.

Classification: LCC DS786 .E735 2016 | DDC 305.800951/5dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015024326

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at cup-ebook@columbia.edu.

COVER DESIGN: Jordan Wannemacher

COVER IMAGE: PETER PARKS/AFP/Getty Images

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

Ben Hillman

Ben Hillman

Antonio Terrone

Franoise Robin

Clmence Henry

Thomas Cliff

Yonten Nyima and Emily T. Yeh

Tyler Harlan

Eric D. Mortensen

James Leibold

Ben Hillman

In the spring of 2008 the Tibet Plateau erupted in protest. On March 10 a group of monks demonstrated for the release of fellow clergy who had been detained by police since the previous year.

MAP 1. Sites of unrest in Tibetan areas since 2008. Australian National University, College of Asia and the Pacific, CartoGIS.

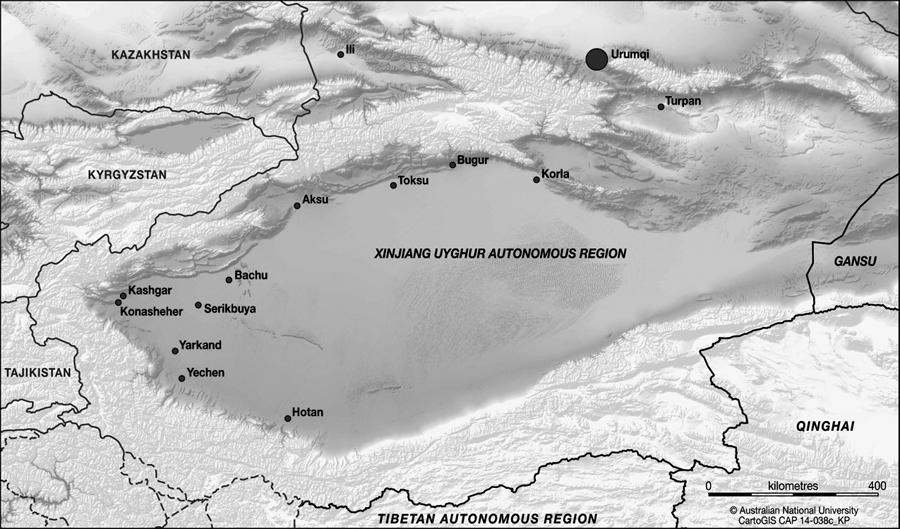

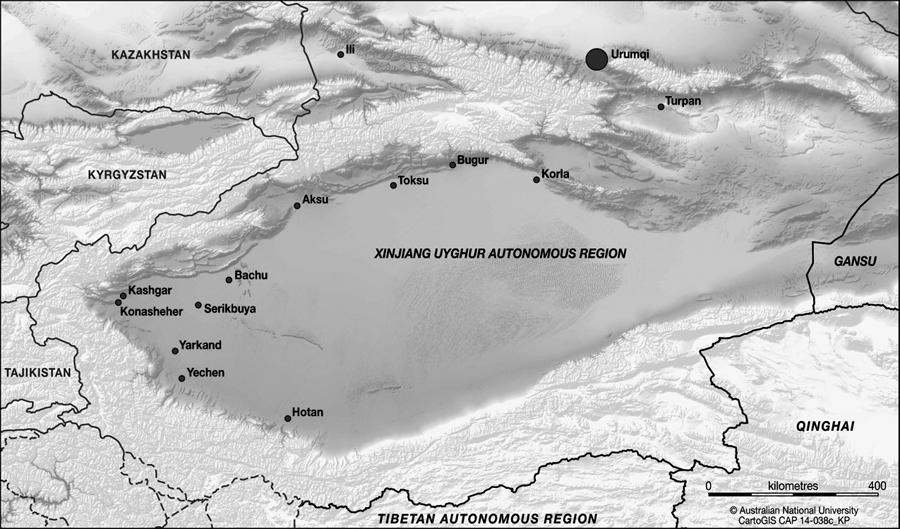

As unrest spread across the Tibet Plateau, trouble was also brewing in neighboring Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang, see

MAP 2. Sites of unrest in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region since 2008. Australian National University, College of Asia and the Pacific, CartoGIS.

In September 2014 Chinese state media reported that forty suspected assailants were either killed by blasts or shot by police during a series of explosions in Xinjiangs Luntai County (AP 2014). And on June 23, 2015, as many as twenty-eight people were killed in an attack on a police checkpoint in Kashgar (RFA 2015).

The Chinese government blames all of the unrest and violence in Tibet and Xinjiang on separatists determined to weaken and split China by fomenting instability. In the case of Xinjiang, authorities blame attacks on separatists linked with the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) and other hostile groups such as the World Uyghur Congress led by Rebiya Kadeer, a prominent Uyghur activist living in exile in the United States. Chinas leaders pointedly blamed Kadeer and her group for orchestrating

Exile groups counter that the unrest is not the work of separatists but a reaction to marginalization and that Tibetan and Uyghur frustrations have reached a boiling point (ICT 2008). Exile groups and disaffected members of the wider ethnic communities charge that Tibetans and Uyghurs are being marginalized culturally and economically in their homelands and that their rights are being systematically violated. According to this view, ethnic unrest is triggered by a deterioration in ethnic securitypeoples perceptions of their ability to preserve, express, and develop their ethnic distinctiveness in everyday economic, social, and cultural practices (Wolf 2006; Horowitz 2000). An exile Uyghur group report accuses the Chinese government of wholesale demolition of Uyghur communities in the name of development. and claiming that radical Islam has emerged as a symbol of resistance following the failure of Uyghur nationalism. The Chinese government vehemently denies such accusations, claiming that state policies protect and promote ethnic traditions. Chinas leaders also routinely point out that Tibetans and Uyghurs have greatly benefited from Chinese Communist Party (CCP) policies, including preferential access to education, employment and welfare, and representation in regional government. According to the official line, any and all political unrest would be resolved if not for the actions of violent separatists bent on destroying China with the help of their foreign allies.

While acknowledging the desire for independence among some sections of the Uyghur and Tibetan communities, international analysts disagree with the proposition that recent unrest in Tibet and Xinjiang can be attributed to the machinations of separatists. International analysts generally agree that the unrest has been fueled by widespread grievances against Although Chinas western provinces have experienced more than a decade of double-digit economic growth, scholars point out that growth in Tibet and Xinjiang has been uneven, noninclusive, and destabilizing. Rapid growth based on mega infrastructure projects has attracted unprecedented numbers of migrants to the region. Because economic migrants generally have superior skills and training, they are able to out-compete the local population for jobs. Nearly all taxi drivers in Lhasa, for example, are non-Tibetan, as are the owners of most small businesses in the city. Similar trends can be observed in Xinjiang. As Tyler Harlan notes in his chapter in this volume, Uyghur entrepreneurs are absent in many industries because they are unable to compete with Han Chinese entrepreneurs who have superior access to local state networks and capital. Indeed, some argue that inequality and economic marginalization are the roots of the recent wave of unrest. Tellingly, more than one thousand Han and Hui Chinese-owned small businesses in Lhasa were reportedly destroyed in the March 2008 riots. In the Urumqi riots of summer 2009 Han Chinese-owned businesses were similarly attacked and destroyed.

Another group of scholars emphasizes cultural and religious factors in their analyses of the causes of the recent wave of ethnic unrest. They argue that government policies in the region have become increasingly intolerant of cultural and religious difference, stoking deep fears among Uyghurs and Tibetans about the survival of their ethnic and cultural distinctiveness (Barnett 2009). In Tibetan areas scholars point to increasing restrictions on monastic life, including the continued use of patriotic education for monks and nuns, as well as limits on the number of monks a monastery can recruit. There are also travel restrictions in place to certain monasteries, blocking access to nonlocal visitors. Scholars have also pointed to suicide notes left by several self-immolators as evidence that fears of cultural survival are fueling such desperate acts. In the case of Xinjiang, scholars have similarly observed heavy state intervention in religious life, including periodic restriction of access to mosques and banning of religious gatherings. Some argue that heavy-handed restrictions on Islamic practices have radicalized many Uyghurs (Hao and Liu 2012; Shan and Chen 2009).

Next page