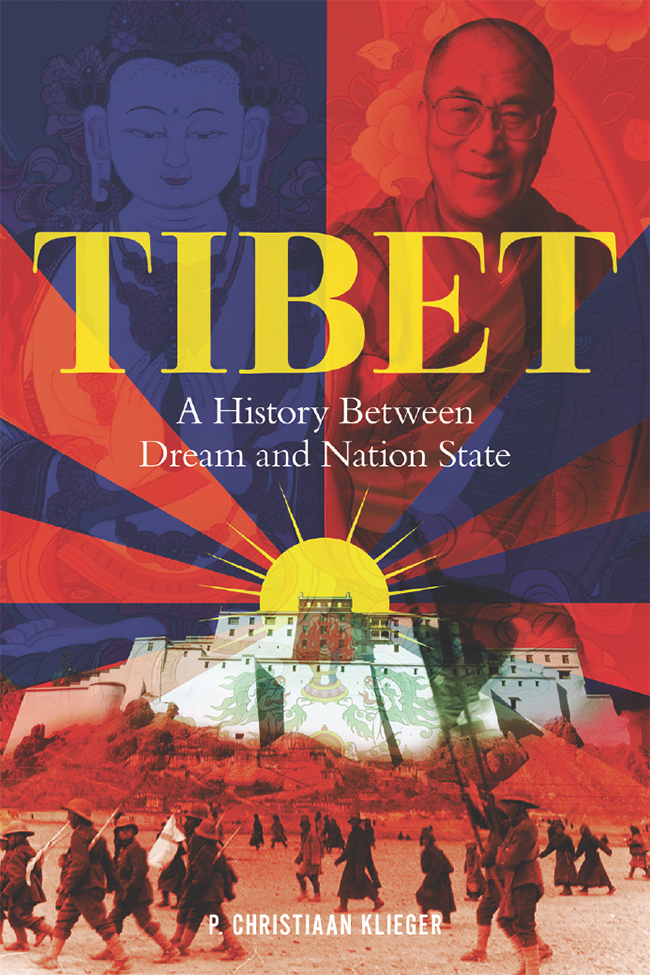

TIBET

TIBET

A History Between Dream

and Nation State

P. CHRISTIAAN KLIEGER

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2021

Copyright P. Christiaan Klieger 2021

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789144031

Contents

Notes on Transliterations

TIBETAN ORTHOGRAPHY PRESENTS a particularly difficult problem in transliteration to the Roman alphabet. This is primarily because the Tibetan spelling is usually vastly different from how it is now spoken, especially in the standard Lhasa dialect. Since 1959, the system derived by Turrell Wylie has been widely used to capture the exact spelling of most Tibetan words, but not its modern sound. The Wylie system is also problematic in transliterating foreign words continually entering the Tibetan language, such as those from Sanskrit. In order to deal with the Wylie inadequacies, under the leadership of Nathaniel Grove and David Germano, the Tibetan and Himalayan Library at the University of Virginia (THL) has developed an Extended Wylie Tibetan System (EWTS) that provides for the use of the standard Latin keyboard for a more comprehensive facility to transliterate Tibetan. An equal consideration is that the lay reader should have some idea how the Tibetan words sound. Germano and Nicolas Tournadre have similarly provided the THL Simplified Tibetan Phonetic Transliteration (2003), which is useful here.

In the Peoples Republic of China ZYPY, or Tibetan pinyin, is used to transliterate Tibetan into a Roman alphabet similar to that used in standard Chinese pinyin. However, it generally does not capture the sound of modern Tibetan language accurately and is not often used in the scholarly world outside of China.

In this work, I use a modified THL phonetic rendering for terms and proper names, followed by the Wylie transliteration in parentheses for the more significant proper names and terms. Some well-known names are rendered as these individuals have been generally known in the Western press.

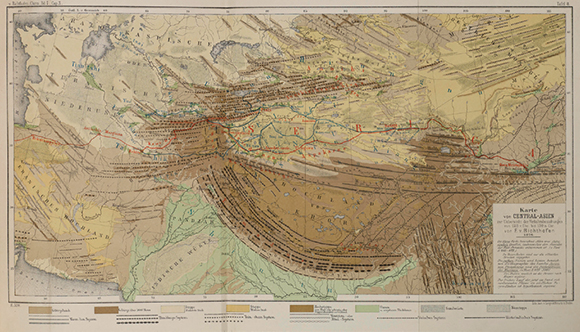

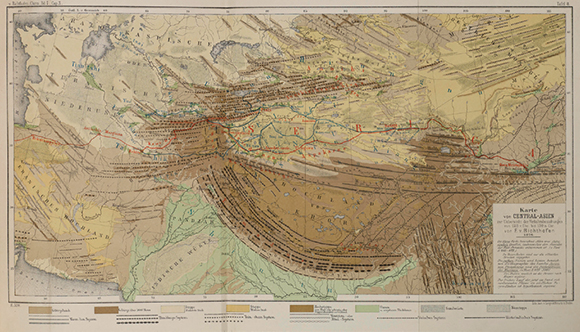

Ferdinand von Richthofen, Map of Central Asia for Overview of Trade Routes and Movements from 128 BC to 150 AD, 1876.

Introduction

T he history of Tibet has long fascinated the world, along with the present controversy about its future: will it ever be (again) an independent nation or will it remain part of China? Is the transnational Tibetan movement a Tibet without Tibet a viable expression of self-determination? How will the succession of the ageing and revered Dalai Lama affect Tibet and the world? Will Chinas leadership continue to be intransigent on the Tibetan question? These are some of the questions to be examined in this work, questions of ideals, legitimacy and nationalism in the still-evolving Tibetan state.

As this book takes a look into the future of Tibet, it also must deal with the past. Tibet is an idea, or several ideas that people have articulated throughout time. These views have formed the Tibetan state throughout history and will inform the future. Considering that ideas of Tibet have been around for 2,500 years and the success of Tibetan refugee settlements abroad, Tibetans can be considered a most persistent people.

There are two themes involved in the problematics of the Tibetan state: first, interpretation of the Tibetan state and its status vis--vis its neighbours is grounded in widely divergent historiographic paradigms. China, India and the West all tend to look at Tibet according to their own perspectives, which seem at times radically different to indigenous ones. The Chinese perspective has been particularly intractable. The modern Chinese state views Tibet as having been an integral part of China for centuries, beginning as early as Tibets affiliation with the Mongol Empire that had also conquered China proper. However, this is the language of the victors. As noted by Christine Sleeter, researchers from dominant social groups have a long history of producing knowledge about oppressed groups that legitimates their subordination.

The paradigmatic dissonance is the heart of the Tibet question on the world stage. The process of self-determination among Tibetan peoples is as active now as it was in the past. It is the mechanism that creates the Tibetan nation. As an active affiliation, nationalism does not always rely upon historic facts in creating a nexus with which a people may identify. The nation-building process often happens through the agency of the imagination; it is not necessarily dependent upon historical precedent, the judgments of international law or the Chinese central government. Real Tibet is somewhere between the dream and the cold reality of the nation state as defined by nineteenth-century European state formation.

Tibet has been a concept for the Tibetans for at least 2,500 years. To describe the Tibetan state solely as either a remote polity on the margins of empire (common in Western historiography) or a local administration of an outer province (most official Chinese state histories) is to fail to do justice to its indigenous statecraft. Tibetan nationalism is real, although often difficult to chart. The essential part of the current deadlocked issue is that modern Tibetans often lack a shared sense of political community with the Chinese state.

Summarizing Tibetan chronology from its first flickers of coalescence as a state to the modern era is also a difficult task. But the main premise of this book is that Tibet was a fully independent state for much of its existence. It was a great empire from the seventh to ninth centuries; in 1249 it became a territory of the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan, a realm that annexed China itself in 1279. Tibet reclaimed its independence from the Mongols in 1349, and from China in 1368. Despite Ming propaganda stating otherwise, Tibet functioned as a completely independent entity until the mid-Qing dynasty (mid-eighteenth century), when the Manchus began to exert their direct influence in Tibetan affairs through the appointment of resident high commissioners (amban) and mandating the use of a golden urn to decide the identities of succeeding high lamas. By 1840, the Qing dynasty was weakening its grip, and Tibet began to resume its independent course. Except for a brief period of occupation by provincial Sichuan troops in the last years of the Manchu imperium (190811) when the Thirteenth Dalai Lama sought exile in India, the Tibetan government exercised effective control over Tibet as a free state. It extended recognition with newly independent Mongolia in 1914. Tibet remained an independent polity until Communist China invaded in 1950. Since that time, Tibetan nationalism has been maintained primarily by over 100,000 refugees living abroad and by homeland Tibetans who risk their livelihoods and lives by perceived splitist actions.