Praise for The High Road to China

There is no more entertaining or informative account Teltschers account of Bogles long stay with the Panchen, based in part on his vivid letters to his sisters, makes this book soar

Jonathan Mirsky, Literary Review

A splendid and fascinating account of early British attempts to establish contact with Tibet and China in the 1770s

Patrick French, Sunday Times

This enthralling book tells the story of Bogles amazing adventure with extraordinary skill

Good Book Guide

Bogles refreshing readiness to accommodate himself to Tibetan ways, and to reflect critically, from the perspective of the mountains and the plateaux, on his own society make a thought-provoking contrast with the pompous stridency of Britains later ventures into China and Tibet Unfailingly interesting and thorough

Julia Lovell, Guardian

Bogle caused a sensation in the Himalayas. When he approached the palace of the ruler of Bhutan, his route was lined with spectators all craning to catch sight of this weird, white-faced alien with tight clothes and funny hair Fascinating

Hilary Spurling, Observer

For Tibetans and Han Chinese these two meetings that Teltscher recreates have a very real political significance Raises issues that powerfully inform our understanding of one of the prickly issues of our time

Fraser Newham, Asia Times

Teltscher really brings Bogles extraordinary travels alive Kipling fans will love The High Road to China

Giles Foden, Cond Nast Traveller

A wonderful story a fascinating book

Bernard Porter, Times Literary Supplement

A vivid look at a lost world

Jonathan Mirsky, Spectator Books of the Year

This is a truly lovely story, told with sympathy and style by a scrupulously careful academic who is a master of her period and its sources. The book is a joy to read, both for the general reader and for the student It has opened up a hugely neglected subject, and will be, probably, forever the authority upon it. This reviewer will read it again with much pleasure

Nigel Collett, Asian Review of Books

A gripping narrative and wonderfully entertaining read

Kirkus Reviews

An impeccably well-researched book, and it is hard to imagine this fascinating story being told with greater sensitivity or skill

Noel Malcolm, Sunday Telegraph

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

Copyright 2006 by Kate Teltscher

First published in Great Britain in 2006

This electronic edition published in 2013 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square,

London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 978-1-4088-4675-9

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books

You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

For Julian,

whose idea it was,

and for Jacob and Isaac,

who grew with the book

In this book I have used Peking for Beijing and Calcutta for Kolkata because these names were current among the British in the eighteenth century.

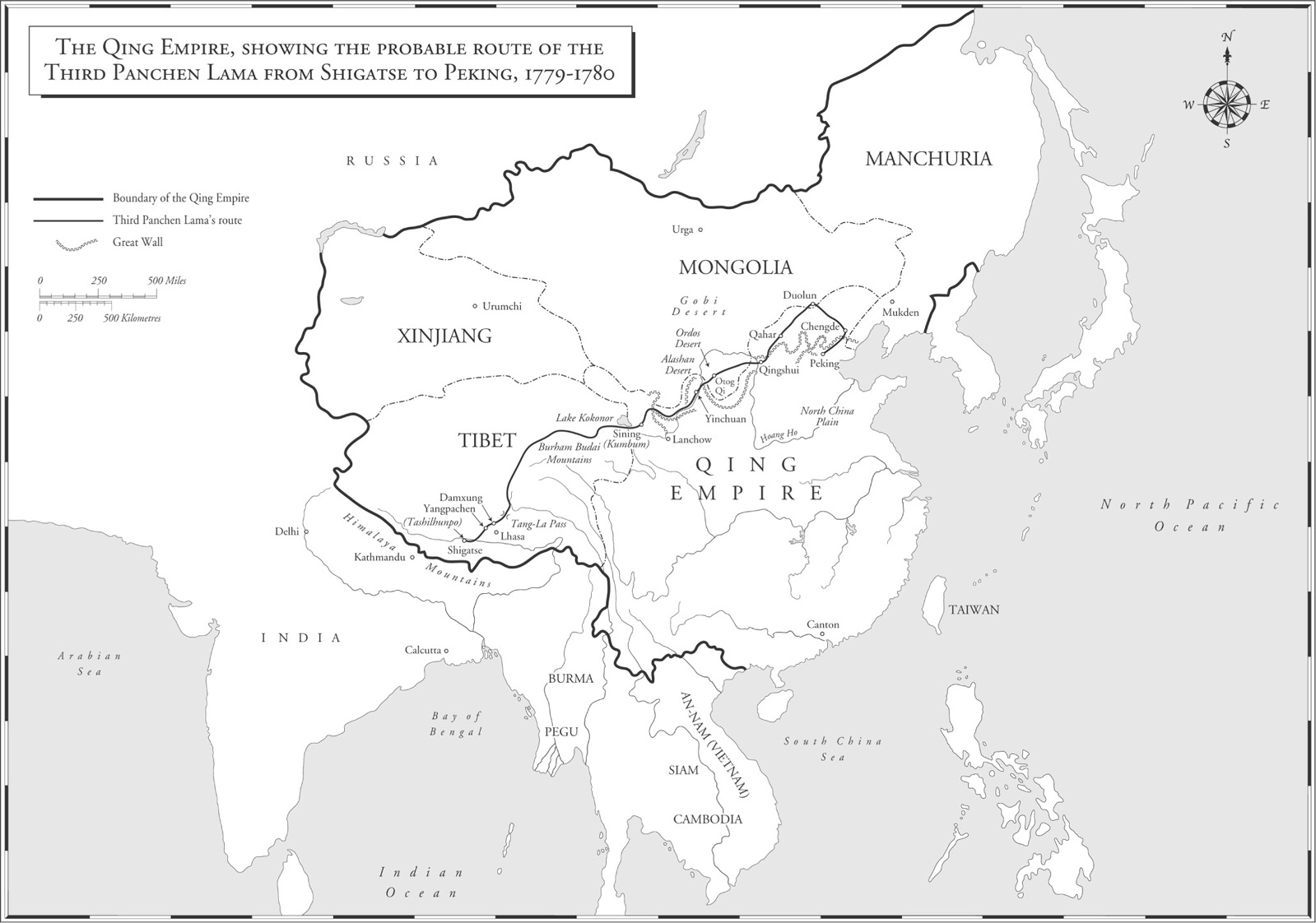

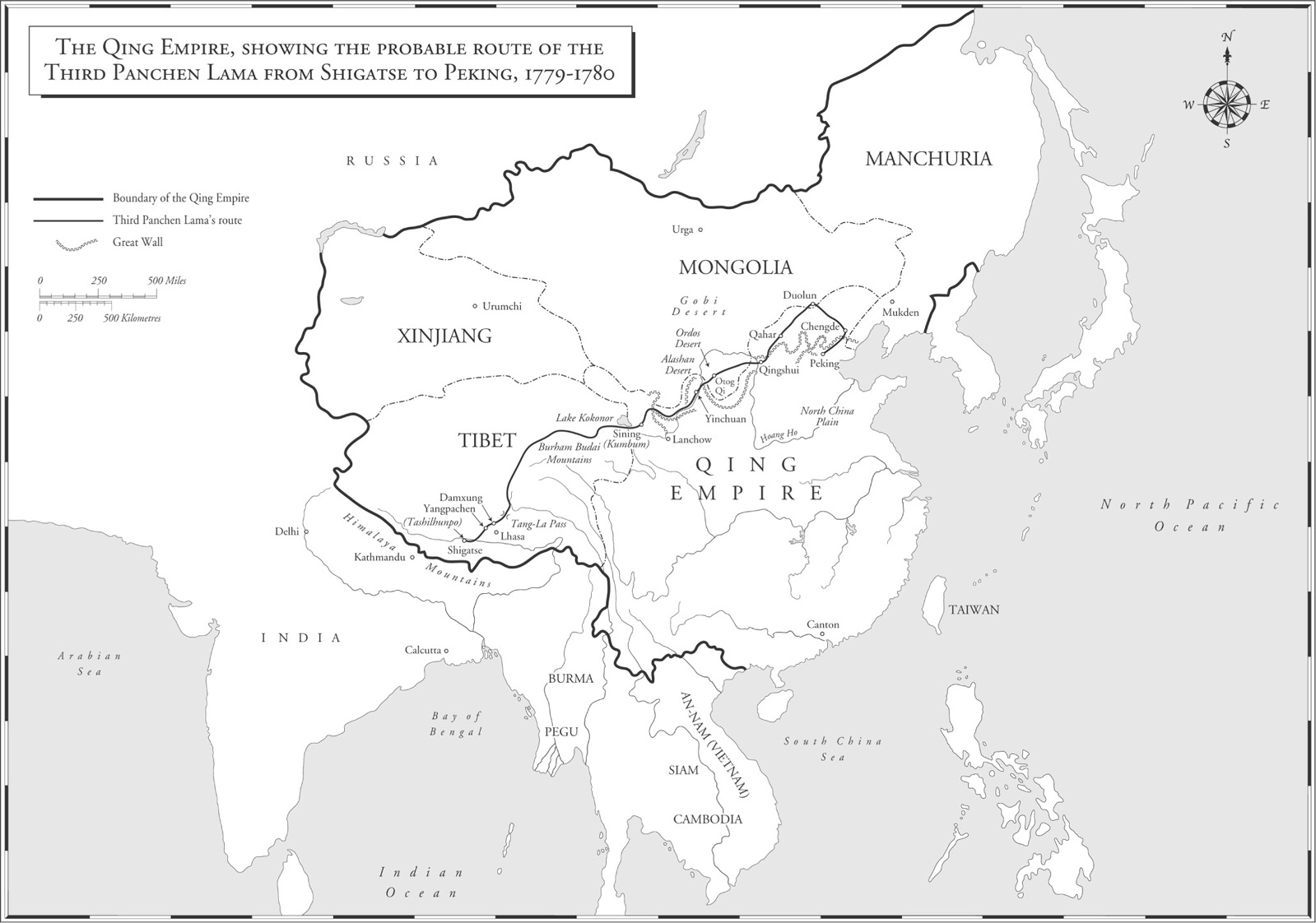

In August 1780, at the imperial palace of Chengde, just north of the Great Wall of China, a meeting took place between two of the most exalted figures on earth. The Qianlong Emperor presided over the worlds largest, richest, most populous unified empire. The Third Panchen Lama was the spiritual head of the Tibetan Buddhist faith. To those who witnessed the encounter, they were more than human. Living enlightened beings, they touched the divine. All power secular and sacred was concentrated in the audience chamber where they sat enthroned, side by side on a golden dais, engaged in conversation.

The Panchen Lama had undertaken the year-long journey from central Tibet to attend the Qianlong Emperors seventieth-birthday celebrations. The festivities were to last some five weeks and spread throughout the palace complex and grounds. Also invited were scores of Mongol princes, there to witness the spectacle of imperial piety and munificence. For above all else, the Qing court knew how to put on a good show. The Panchen Lama officiated at the ceremony for the Long Life of the Emperor, dispensed multiple blessings and, in private, initiated the Qianlong Emperor into Tantric mysteries. During his visit, there were banquets in a great Mongolian tent erected in the Garden of Ten Thousand Trees. Seated at tables covered in yellow satin, the Emperor and Lama dined off plates of gold, the other guests off silver. The between-course entertainment consisted of magic shows, wrestling matches, acrobatics and operatic scenes staged by the court eunuchs. Three weeks into the festivities, there was a grand firework display. Pyrotechnic gardens bloomed, fiery dancers twirled and, in a final dazzle, the Chinese characters for Place of All Happiness blazed through the darkness.

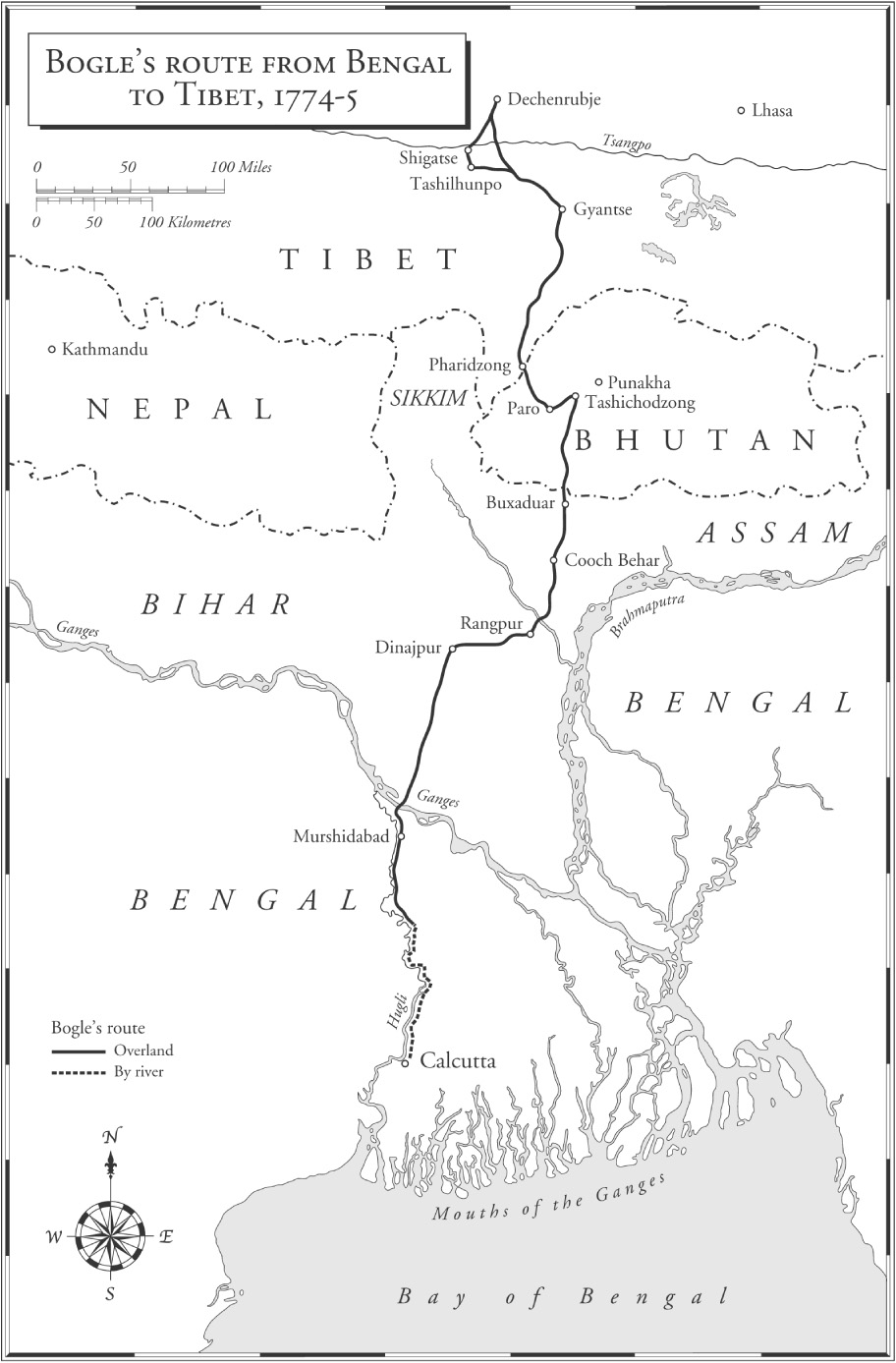

In quieter moments, there were opportunities for the Lama and Emperor to discuss affairs of state. On one occasion, when the dancing boys had been dismissed, the Lama begged leave to raise a matter with the Emperor. Following the dictates of friendship, he felt bound to mention the country of Hindostan (northern India), situated to the south of Tibet. The Governor of Hindostan and he were friends, he said, and it was his wish that the Emperor too would enter into friendship with the Governor. Such a small request, the Emperor courteously replied, was easily granted. What was the Governors name? How large his country and how great his forces? To answer, the Lama summoned a humble member of his entourage, a Hindu trading monk called Purangir who knew the country well. Hindostan was far smaller than China, Purangir said, and its army numbered some three hundred thousand. The Governor was called Mr Hastings. So it was, the story goes, that the name of the British Governor General, the head of the East India Company in India, reached the ears of the Manchu Emperor.

When I first read the account of this conversation, I was intrigued by the possibilities that it raised. In the late eighteenth century the British longed to open relations with the Emperor of China. But the imperial court was utterly inaccessible to European traders, who were confined to seasonal trading at the southern port of Canton. Some twenty years earlier, a British merchant who had attempted the journey to Peking to present a petition to the Emperor had been stopped a hundred miles short of the Forbidden City and punished with three years imprisonment. China then, as now, appeared a most alluring market to Western companies. All the more so because European traders were banned from entry and commerce was subject to strict regulation. British merchants fantasised about the day when Chinas trading rules might be relaxed and a huge potential market and corresponding profits unleashed. The first step would be to open amicable relations with the imperial court. To the eighteenth-century British reader, the commendation of Mr Hastings to the Emperor would have sounded like the answer to a merchants prayer.

Next page