Table of Contents

For my wife, Tanya, and my mother, Jean

THE TIBETAN AUTONOMOUS REGIONAND GREATER TIBET WITHIN CHINA

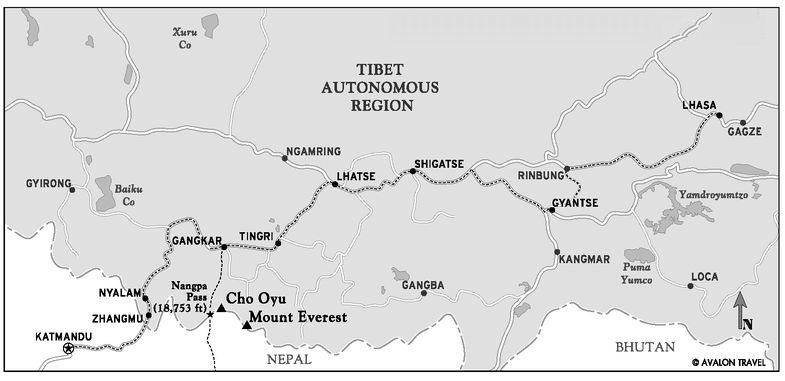

TIBETANS ROUTES TO INDIA

Introduction

THE BASIS FOR THIS BOOK IS SIX YEARS OF LIVING IN CHINA AND writing about the epochal changes that transformed the lives of hundreds of millions of people. When I first arrived in Beijing in 2003, the working environment for foreign journalists was not easy. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs required us to inform our minders every time we planned to take a trip out of the capital. Regulations also stated that we needed official approval for every single interview we conducted, including people on the street. In reality, most of us flouted the rules. We had to: We couldnt do our jobs waiting endlessly for approval and then travel with local Foreign Office minders constantly by our side. When we got caught outside of Beijing, local security officials would often demand that we write a ziwo pipinga selfcriticismacknowledging that we broke the regulations.

The atmosphere changed in early 2008. As part of its obligations to the international community for hosting the Summer Olympic Games, China relaxed the rules for foreign journalists. We no longer had to inform the ministry of trips or obtain permission for interviews, as long as the interviewees were amenable to taking questions. To its credit, China has maintained the more open environment after the Games. But some restrictions are still in effect. Tibet is off limits to journalists unless they obtain a permit, akin to a visa, which is rarely available. Indeed, Tibet is one of several topics that remain virtually radioactive for the ruling party. In journalistic shorthand, those topics are the three Ts and one Fmeaning Taiwan, Tibet, and the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement crushed by Chinese troops in June 1989; the F refers to the Falun Gong meditation sect that rapidly expanded in China in the late 1990s before it was harshly suppressed and declared an evil cult.

In 2007, a professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology set off an academic brouhaha with an article in the respected Far Eastern Economic Review. Carsten A. Holz suggested that Western scholars held an often unacknowledged interest in not provoking China. First, those whose mother tongue is not Mandarin spend years mastering the language, an investment they dont want to go down the drain. Then when it comes to field research, scholars usually must cooperate with academics in China to collect data. Since Chinas research institutions and universities answer to the party, surveys are conducted in a manner that is acceptable to the party, and their content is limited to politically acceptable questions, he wrote. Others rely on prized key connections within the party or at major institutions to do research, constraining their actions. Not all China researchers feel pressure equally, Holz wrote, noting that political scientists and economists might feel it the most.

The article raised a ruckus among China scholars, some of whom protested Holzs charges. It was a prickly issue. No Western scholar would want to admit to tailoring research to maintain crucial access in China. And in fact, some bold enquiry on sensitive topics does exist. But I found the matter had substancenot only for academics but also for business executives willing to bend core principles of their companies in order to enter the huge China market, and even for some journalists who have made reporting from China their long-term career calling. An experienced China hand who suddenly finds himself or herself on Chinas black list, unable to get a visa to attend conferences or confronting cancellation of residency, may face a major career setback. While the number of such cases may be small, perhaps a dozen or two dozen people, they have a large impact, causing many others to hesitate to conduct sensitive research in China or speak out about events there.

Ive personally experienced the kind of pressure China can bring to bear. One day in November 2008, I received an email that gave me a jolt. The bureau chief in Washington for the media company that employs me, McClatchy Newspapers, wrote that Chinese diplomats in San Francisco were asking to see the chief executive officer to talk about my news coverage of China. The email arrived while I was traveling in Dharamsala, India, reporting on Tibetan issues. I wrote back that I had no idea what might be troubling Chinas Foreign Ministry. But my mind raced. It was hard to concentrate over the next few days. I knew that this level of interest in my work would certainly cause editors to exhibit extra care. It might even affect my own actions, perhaps subconsciously.

A month or so later, I was in Washington and asked the bureau chief what became of the meeting with the Chinese diplomats and the CEO. They wanted to know about your book on Tibet, he said. I nearly fell on the floor, both in relief and in shock. How would the Chinese diplomats even know that I was writing a book, not to mention its subject? The answer was obvious. I hadnt had contact with Foreign Ministry officials for over a year. So the only way they could know of my plans to write a book (which I had shared with very few people) was if someone in Chinas state security apparatus had been monitoring my email and listening to my phone calls. This alone wasnt a surprise. Like all diplomats and foreign correspondents based in China, one presumes that state security agents monitor microphones installed in apartments, offices, and cars. China is increasingly free, especially for those Chinese or foreigners who have no interest in politics. But for anyone else deemed a threat or touching on sensitive topics, the state has a thousand eyes and a thousand ears. They had been listening to and watching me. They wanted me to know it, so they sent a shot across the bow of my employer. I found it chilling.

But what happened to me is amplified for Tibetans. This book unfolds over the course of a long journey, in reality a series of journeys over several years. It reveals the Tibetan experience through many perspectives, among them those of the nomad, the monk, the angry young exile, and the unique story of a young Tibetan woman with ties to the highest level of the ruling party. With each chapter, the chasm between Tibetan and majority Han Chinese comes into sharper relief. Behind largely fictitious verbiage pledging autonomy, and while promising leapfrog development, Beijing emasculates Tibetans. It has opened the floodgates to domestic migrants who weaken the Tibetans grasp of their identity and culture. In my research for this book, I traveled to the frigid reaches of the high Himalayas, across Nepal and India, and with the Fourteenth Dalai Lama on a lengthy speaking tour in the United States. The reader will observe how China has used its growing might to thwart Tibetans at nearly every turn, at home and abroad, in the digital realm and in the lawmaking halls of foreign capitals from Canberra to Washington.