ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

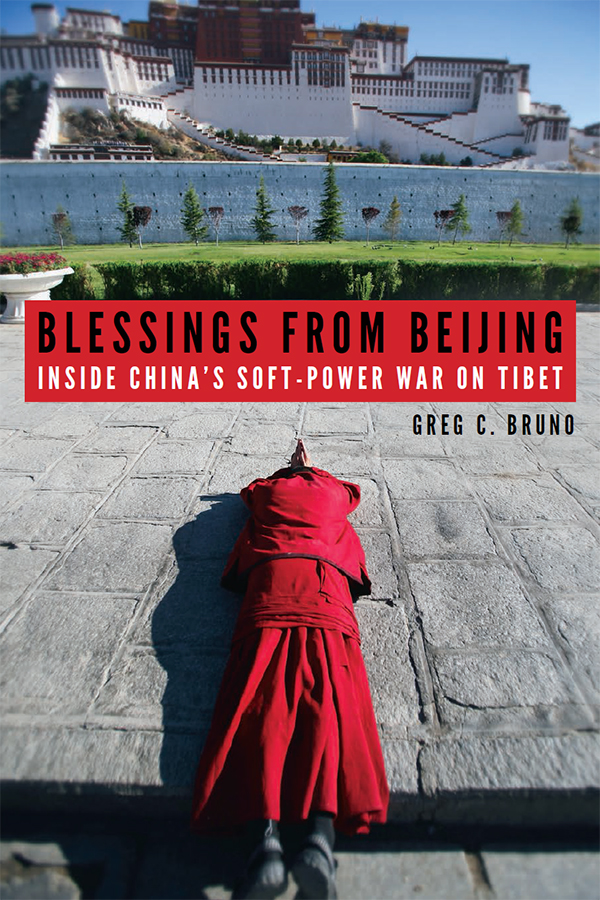

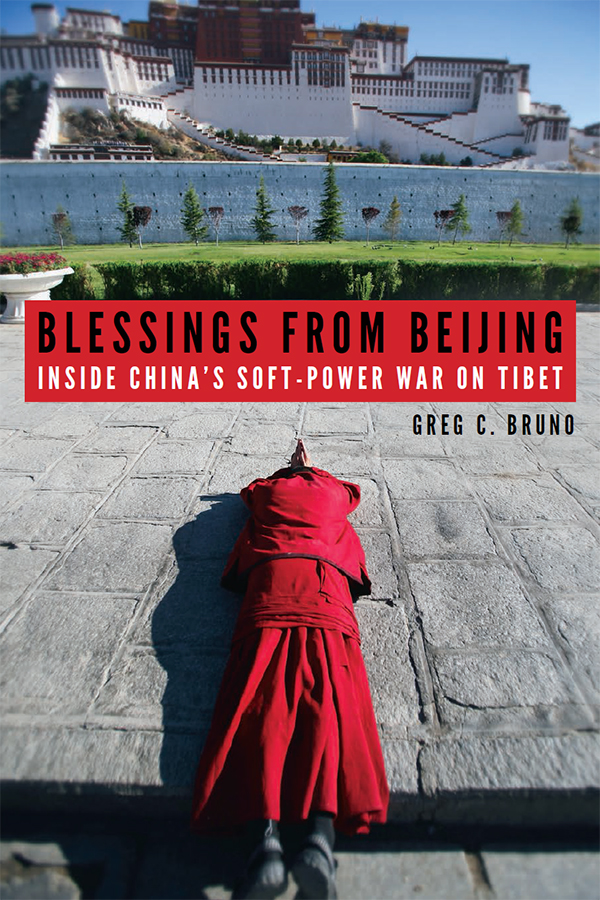

Every work of nonfiction owes a debt to the openness, energy, and generosity of its contributors. It is those closest to the talethe university scholars, the humanitarian aid workers, the subjects themselveswho guide authors from the edge of fiction toward the stability of narrative fact. Books based on the lived experiences of others fail to exist without the protagonists spirit, knowledge, and willingness to share their stories.

Hundreds of such experts are behind this story. Some of them appear on the pages that follow; many do not. But all of them allowed a stranger to probe their pasts, plumb their insights, and peer into their world, however briefly. I am grateful to them all.

Two scholars of contemporary Tibet merit special mention. In 1997, Hubert Decleer and Andrew Quintman were the academic guides for my study of Tibet through the School for International Training (SIT). Hubert and Andy emanate an infectious passion for the people, places, and customs of Tibet, and their love of their subject deeply influenced the life trajectories of their students, myself included. It is thanks to their mentorship that I developed an unshakable curiosity about the modern challenges facing the Tibetan diaspora.

Had it not been for SIT, this book would never have materialized, for it was through the school that I first met Purang Dorjee, the elderly shopkeeper whose life has informed many aspects of this narrative. Purang took me into his home in McLeod Ganj during the winter of 1997 and inspired me to learn more about his people. I am forever indebted to Purang, for welcoming me into his life two decades ago, and for inviting me back so many times since.

Rinchen Dharlo, the former president of the Tibet Fund in New York, and Robyn Brentano, formerly the Tibet Funds executive director, were gracious with their deep contact lists and extensive knowledge. Each was quick to introduce me to Tibetan sources and opened more doors than I can possibly count. Without them, this book would not have been possible. For one, it was Robyns invitation, in 2009, that led to my brief audience with the Dalai Lama. Robyn also reviewed portions of the final manuscript, providing invaluable perspective on contemporary events.

Kate Saunders, at the International Campaign for Tibet, was also incredibly generous with her time. She, too, has deepened my understanding of the challenges facing Tibetans, on both sides of the border. I am particularly grateful for her assistance in securing an interview with the Seventeenth Karmapa, one of the most important Tibetan religious figures whose place in history is still being written. Kate also connected me with Adam Koziel of the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, whose sharp eye helped keep a number of factual errors from entering the final manuscript.

Esther Kaplan, at the Nation Institutes Investigative Fund, was among the first to recognize the importance of this work. The institutes grant, in 2010, enabled me to conduct fieldwork in Nepal and North India, kick-starting the books reporting process. As one of the few organizations still funding independent investigative journalism, the Nation Institute merits a special thank-you.

Because most journalists make lousy historians, I am deeply indebted to those scholars and experts who spent hours in person, on the phone, or with my manuscript printed out in front of them, steering me through the dizzying and often politicized story of Tibets modern history. Robert Barnett, of Columbia, and the independent Tibet scholar Matthew Akester were most gracious with their time. Their combined knowledge of Tibets past and present informed many aspects of this story, and I am forever indebted to these two masters of Tibetan history.

Additional academic insights were offered, and eagerly accepted, from Fiona McConnell of Oxford; Christopher Hughes, Stephan Feuchtwang, and Andrea Pia of the London School of Economics; and from Gary Beesley, whose knowledge of the murky world of intra-Tibetan religious rifts is unrivaled. Each of these experts kindly reviewed key sections of the text, offering expertise on topics as far-ranging as Chinese history, foreign policy, and Tibetan Buddhism.

In Nepal, two human rights activists are doing yeomans work in protecting vulnerable Tibetan refugees from prosecution. In 2010, when I began this study, Sudip Pathak and Sambu Lhama seemed the only advocates working to protect Tibetans in Nepal from the ever-tightening grip of Chinese influence. These tireless human rights champions took me under their wing and opened doors to Nepals legal and humanitarian communities that would have been inaccessible otherwise.

At the Council on Foreign Relations, in New York, Michael Moran and Robert McMahon were inspiring storytelling mentors, and equally inspiring bosses, permitting me to sojourn in Asia on an extended book-reporting sabbatical when I first began this project. Without their flexibility and support, I am certain this endeavor would never have gotten off the ground.

Throughout the reporting, writing, and publishing process, I leaned heavily on friends and former colleagues to review manuscript drafts, produce maps and other material, and offer moral support. Matthew Corcoran, in particular, spent hours reading and providing thoughts on pacing, structure, and flow. I am certain that without his energy, Blessings would be far less readable than it is today. Marin Devine, a gifted graphic designer, put together the maps that appear here, offering her expertise for little more than the cost of an overpriced gin and tonic. Edward Brachfeld provided the initial inspiration for my pursuit of this topic, while Suzanne Strempek Shea offered invaluable advice on successfully navigating the publishing process.

My agent, Carrie Pestritto, was a fantastic advocate at every juncture and saw in Blessings a story that needed an audience. She was relentless in finding one, and served as a constant source of optimism during what can be, for many authors, a drawn-out process of rejection. Her skillful review of proposal drafts, and persistence in pitching them, brought the search for a publisher to a positive conclusion.

My editors at UPNEStephen Hull and Susan Abeland Glenn Novak shepherded multiple versions of the manuscript through the editing churn with great professionalism and grace. Their deft handling of diction and prose ensured that this project was, from start to finish, a collaborative endeavor.

Many others educated me on issues related to Tibet and the Tibetan diaspora; I am grateful to all of them, including Abanti Battacharji, Olrich Cerny, Rhoderick Chalmers, Yeshi Choedon, Tenzin Choepel, Ginger Chih, Michael Davis, Paula Dobrianski, Sonam Dorjee, Tenzin Dorjee, Thondup Dorjee, Tenzin Drakpa, Nathan Freitas, Zhu Guobin, Dorje Gyaltsen, Lobsang Gyatso, Trinlay Gyatso, Nigel Inkster, Sonam Khorlatsang, Vijay Kranti, Margaret Lau, Mary Beth Markey, Kai Meuller, Karma Namgyal, Tsewang Namgyal, Lobsang Phelgyal, Tashi Puntsok, Sophie Richardson, Jigme Lhundup Rinpoche, Kirti Rinpoche, Samdhong Rinpoche, Thupten Samphel, Lobsang Sangay, Phunchok Stobdan, Lubum Tashi, Lhadon Tethong, Tenzin Tethong, Tenzin Topten, Bhuchung K. Tsering, Tempa Tsering, Kunchok Tsundue, Tashi Wangchuk, Kalsang Wangmo, Robert Weinreb, and Tenzin Woeser.

Blessings would still be an obsession, rather than a bound text, had it not been for the support and encouragement of my family. My parents, Kenneth and Claire, were unconditional cheerleaders, funding my university travels to Tibet in the 1990s, and years later serving as eager readers of multiple drafts. Mom and Dad: I cannot thank you enough for the support youve given me, early and often. These

Next page