Preface

The Himalayas has been a theatre of competition by proxy between India and China for over half a century now. The two countries have been locked in a long-standing unresolved border dispute in this extensive mountain range that stretches from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh. It has witnessed dramatic military stand-offs that have not turned bloody since November 1962. This aside, Chinas meddling with Himalayan river flows, especially the diversion of the Brahmaputra and Sutlej waters for hydroelectric dam construction, has frequently chafed India. Indias concerns also include Chinas increasing footprint in Nepallong regarded as part of the formers sphere of influence.

The military dimension of the Himalayas, especially Chinas systematic building of infrastructure, means for reconnaissance and surveillance and operational capabilities, has remained a part of Indias security discourse for decades. The US Department of Defense has occasionally been cautioned about Chinas increasing troop build-up along the Indian border in addition to it establishing naval logistic hubs in Pakistan.

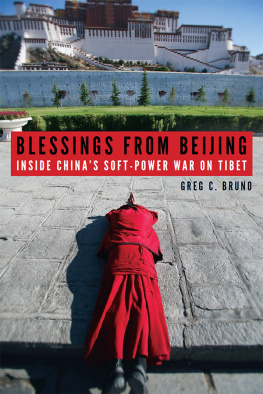

Very little is known about the pattern of other shadowy wars that are non-military in nature, launched by both sides in the Himalayas; these are not easily discernible but have an equally powerful impact on the shaky balance of Himalayan security.

China has been standing by Pakistan to destabilize the Kashmir Valley through proxy sponsorship of terrorist activities and by consistently blocking the listing of Pakistan-based terrorists in the United Nations (UN) list. In the eastern Himalayas, China has been playing the religion card to claim the Tawang region from India. The Chinese have also openly supported various insurgent groups, including the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA).

In the central Himalayas, China supported the Maoist insurgency during the civil war in Nepal during 19962006. It continues to influence the people of Nepal to undercut their natural affinity with India.

While China also faces problems both in its Xinjiang province and the Tibet Autonomous Region, so far no direct Indian involvement has been observed in either. India has been engaged in a shadow-boxing game by holding on to its Tibet card for almost six decades. In 2016, New Delhi tried to add the Xinjiang card to its arsenal by issuing a visa to an Uyghur activist to attend the Eleventh Inter-ethnic/Interfaith Leadership Conference organized by Dharamshala. For the moment, though, China seems to be in firm control of both Tibet and Xinjiang, and there are no visible signs of it facing any major challenges on either of these fronts. Of course, one cannot predict what will happen in the longer run.

According to conventional wisdom, the Indian Himalayan region at least is peaceful, and this freedom of religion and democracy has ensured stability on our side of the mountain range. But, sadly, this is no longer the case. The Indian Himalayan belt from Tawang to Ladakh has been subject to a string of incendiary events which are threatening to pitchfork the region into crisis.

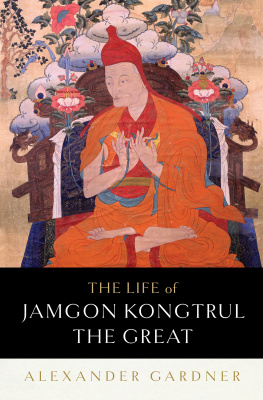

The Indian Buddhist Himalayan complexity is fast changing and could be a source of considerable concern for Indias security. In part, this seems to be arising from an excessive Tibetan influence (Tibetanization) in the Himalayas via a gradual taking over of Indian institutions by Tibetan lamas in the Buddhist Himalayas. Worryingly, more powerful lamas are seen setting up their parallel sectarian networks and infrastructure from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh. They have also brought along their cultural and sectarian affiliations, differences and discords (intrinsic to Tibetan politics) that could potentially destabilize the Indian Himalayas.

The long-term presence of Tibetan refugees in India and the future of the institution of the Dalai Lama have created a sense of uncertainty. The Dalai Lama has already indicated that he would possibly take his next rebirth in India. Even for the main stakeholder, the US, to play Tibet politics, requires controlling the Tibetan leaders next reincarnation. This would mean the Tibetan issue will continue to create a situation to make the Himalayan region a bigger geopolitical tinderbox. In the process, Indias own Buddhist institutions are speedily undermined to the detriment of Indias interest. This is where China would try to win both the Tibetan and the Buddhist Himalayan game.

The Buddhist Himalayas will continue to remain a contested geo-cultural landscape between the competing narratives of India and China. However, in the current scenario, Indias interests in the Buddhist Himalayas remain even more compromised than during the colonial period, when British strategists were able to play the Himalayan game more perceptively.

The British could understand the dynamic interplay between the Tibetans vis--vis Himalayan Buddhism, especially the devotional power of various sectarian groups within Lamaism, to achieve the results they desired. They created buffer zones and an Inner and Outer defence line for protecting its Himalayan frontiers.

However, in the current situation, India seems to lacks sufficient wherewithal to understand the critical interplay between Buddhism and the Himalayas, and this has weighed heavily on the minds of the Dalai Lama and his government-in-exile. Of late, the Tibet card is being redefined, albeit on the grounds of Buddhist diplomacy.

The geopolitics of the Himalayas has become more obscured ever since the mantle of Indias TibetChina policy has fallen into the hands of the Americans. The Tibet issue has already overshadowed the Himalayan identity, which has served to further blur the Indian frontier outlook. In contrast, the Chinese may have been thinking about playing the reverse strategic depth policy by leveraging the critical interplay between Buddhism and the Himalayas.

In the post-1950s period, China never viewed the Himalayan ranges as a barrier, but rather a bridge to create additional spheres of influence.

Gone are the days when India exercised a complete stronghold over the Himalayan region. If the developments so far have proven anything, China has gradually and successfully expanded its influence in Nepal.

Beijing has even been setting its gaze on Bhutan through various diplomatic means, not completely without success. The Bhutanese public perception about China certainly seems to have undergone a substantive change over the years.

China also has its eye on other parts of the Himalayas which are equally fertile places for Chinese influence to grow because of their proximity to Tibetan culture.

There are already direct and visible pointers of the Chinese beginning to harness Tibetan resources for steering the Himalayan game in their favour. In fact, the entire belt has witnessed an intense process of Tibetanization, from the point of view of cultural as well as political mobilization. Most Indian monasteries have already fallen under the control of Tibetan lamas.