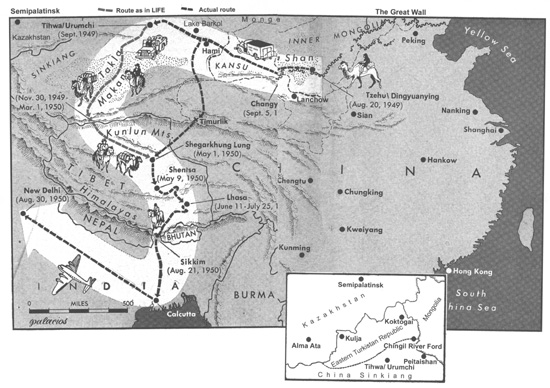

Map from Life magazine, November 1950, edited to show actual journey

INTO TIBET

THE CIAS FIRST ATOMIC SPY AND HIS SECRET EXPEDITION TO LHASA

THOMAS LAIRD

Copyright 2002 by Thomas Laird

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Laird, Thomas.

Into Tibet: The CIAs first atomic spy and his secret expedition to Lhasa / by Thomas Laird.

p. cm.

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9662-0

1. United StatesRelationsChinaTibet. 2. Tibet (China)RelationsUnited States. 3. Espionage, AmericanChinaTibet. I. Title: Americas secret expedition to Lhasa. II. Title.

E183.8.T55 L35 2002

303.4827305i5dc2i

2001058459

DESIGN BY LAURA HAMMOND HOUGH

Grove Press

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

TO JANN FENNER

AND MY PARENTS,

LOIS WILSON AND TOMMY LAIRD

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

DURING SIX YEARS of research, I tracked down thousands of pages of U.S. government documents, dozens of letters, two diaries, and the survivors of these events. Several of the government documents quoted in this story were obtained only through Freedom of Information Act requests that took several years to bear fruit. Every assertion of fact in this book is based on these documents, published sources, or interviews with specialists, eyewitnesses, and the survivors of the journey. When you see a conversation in quotation marks in this book, they indicate that a person who was at that location at that time recalls those words being said. Or the quotations were recorded in writing at the time or shortly afterward. The tense of these quotations has sometimes been altered to fit them into the narrative. If conversations are not in quotes, it indicates that after exhaustive research I believe that this is what was said.

Occasionally, recalling events of fifty years ago, survivors recollections fail, or are at odds with others memories; when this is so I indicate that in the source notes and tell you what happened to the best of my understanding. Descriptions of places and weather and clothes are based on testimony from the survivors, published accounts, and my own experiences in Tibet.

I have given myself more leeway with descriptive passages. I have occasionally conflated events or conversations, which did occur, into one time and place; these few instances are also noted in the source notes. A few names have been changed, but only for minor characters. For the ease of the average reader I have chosen to use the standard spellings for place and people names that were current in America at the time when the events in this book took place. Thus todays Xinjiang is Sinkiang, Xian is Sian, Beijing is Peking, and Osman Batur is Osman Bator.

It is important that the reader understand that when I believe there is doubt about what happened, or what was said, I alert you to that doubtif not in the text, then in the source notes. For fifty years great pains were taken, and even now continue to be taken, to conceal what truly happened before, during, and after this expedition.

PREFACE

INTO TIBET TELLS the story of a secret American expedition to Tibet in 1949 and 1950 that has never before been told. Only two of the five men who set out survived. Theirs was a two-thousand-mile, one-year trek, and it is one of the most remarkable adventure stories of the twentieth century. The two survivors are the only Americans alive today who have walked across Tibet. However, their story is more than just an adventure tale. The survivors are the last Americans ever to meet the Dalai Lama in independent Tibet. China invaded Tibet six weeks after they left the country. Yet today these men and their journey are not part of history. The primary purpose of this book is to tell as much about their remarkable journey as we are allowed to know.

The facts remained hidden behind a cover story for fifty years. The moment I stumbled upon the first hints of this adventure in the dusty files of the National Archives in Washington, D.C., I felt great sympathy with the men who had trekked through the Himalayas half a century ago. Although I am an American, at forty-eight I have spent more of my life in the Himalayas than in the United States. I first arrived in Nepal in 1972, a nineteen-year-old kid, traveling alone overland from Europe. I have been based in Nepal since, and have made more than fifty treks in the Himalayas. In 1991 I became the Asiaweek reporter for Nepal.

For much of 1991 and 1992 I lived in Mustang, a remote Buddhist barony within Nepal that juts up through the Himalayas onto the Tibetan Plateau. The people, their culture, and their language are essentially Tibetan, though Nepal has ruled the area since about 1770. The feudal serfs of Mustang were liberated from their noble masters only in 1956. Incredible fourteenth-century Tibetan Buddhist murals have survived in Mustang, while the Chinese have destroyed 90 percent of such art in Tibet. Mustang became a time capsule of preinvasion Tibetmade more alluring by the fact that it was a forbidden land. The Nepalese government forbade foreigners to visit Mustang during the thirty years before my one-year permit was issued. Nepal and China had not forgotten the covert Central Intelligence Agency support for a Tibetan guerrilla movement based in Mustang after the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950. When the United States halted support to the Tibetans in the 1970s, China and Nepal agreed to disarm the guerrillas. Nepalese sensitivities to this Cold War historyand, some said, Chinese pressurekept Mustang closed to all non-Nepalese during the 1970s and 1980s even as tourism became Nepals major industry. Mustang became the most coveted travel destination in Nepal.

In 1990 Nepal erupted into revolution. My photography of violent clashes in front of the Royal Palace in Kathmandu was published in many international news magazines. The new government that came to power felt I had risked my life getting pictures out to the world. The new prime minister asked me if there was something I wanted in Nepal, after having lived there for twenty years. I said I wanted to go to Mustang. So in 1991 the government issued me the first (and only) one-year travel permit for Mustang. I spent most of my time there shooting 50,000 photographs, working on a book that Peter Matthiessen and I eventually published, titled East of Lo Monthang: In the Land of Mustang.

At the end of my year in Mustang I was eager to fly to the National Archives in Washington, D.C. A number of searing experiences drove me there.